Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

*1Kenneth Bachmann, 2Christopher Bates and 3Peter Zangara

Received: July 03, 2017; Published: July 07, 2017

Corresponding author: Kenneth Bachmann, Ph.D., F.C.P. Vice President of Pharmacoinformatics and Cofounder, CeutiCare Co., Inc, Distinguished University Professor of Pharmacology, The University of Toledo, 7619 Olympic Parkway Sylvania, OH 43560, USA

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000177

A 68 year male patient (KB) presented in August 2014 with profound muscle weakness of the hip and legs. Treatment with an 8 cycle regimen of CHOP for NHL 10 years earlier led to complete remission. He had also been treated for BPH with doxazosin, finasteride, and tadalafil. He was otherwise in good health with an eGFR of 77 mL/min. Rosuvastain had maintained lipid levels below targeted values for two years. He was subsequently referred to a neurologist (PZ). Radiological, laboratory, and neuromuscular tests were negative. KB abstained from rosuvastatin beginning in March, 2015. Subjective feelings and objective measures of muscle weakness began improving. Pravastatin 20mg challenge exacerbated weakness, and was stopped. Weakness improved until atorvastatin was initiated in October 2015, but was discontinued after only two doses when leg weakness worsened. The patient has been statin-free since November, 2015. On follow-up on February 10, 2016 muscle strength was objectively normal.

Keywords: Statins; Myelopathy; Myalgia; Myasthenia; Myositis

Abbreviations: MG: Myasthenia Gravis

In August 2014 KB, a 68 year old Caucasian male (KB) presented at the office of his Internist (CB) for a semi-annual check-up. KB had been diagnosed with Stage 3 mediastinal NHL early in 2004, and had been treated with eight cycles of CHOP that omitted vincristine only in the eighth cycle due to neurological effects that prevented normal hand and finger movement bilaterally. Splenic lesions observed on PET scans led to a splenectomy in 2005, however no malignant cells were found upon biopsy. He remained in complete remission since the conclusion of therapy. He had also been treated medically for BPH for nearly two decades with single daily doses of doxazosin mesylate (8mg) with the addition of finasteride (5mg) beginning about five years ago. Tadalafil (Cialis) 5mg had recently been added for several months as well. Rosuvastatin (20 mg daily) had been taken for hyperlipidemia for several years, successfully keeping all lipid values well below targeted goals, and HDL-cholesterol well above targeted goals. Other medications included fluticsasone proprionate/salmeterol (250mcg/50mcg) once daily and monteleukast (10 mg) daily for chronic, mild asthma, and levothyroxine (88 mcg) daily for hypothyroidism thought to be secondary either to NHL or CHOP treatment. Asthma had been very well controlled with no need for rescue inhalers ever since the initiation of the fluticasone/salmeterol combination and monteleukast. Additionally, KB reported a regular exercise routine of jogging (2 miles, three times weekly) and weight and cardiovascular/weight exercises (P90X™) also three times per week.

and monteleukast. Additionally, KB reported a regular exercise routine of jogging (2 miles, three times weekly) and weight and cardiovascular/weight exercises (P90X™) also three times per week. were negative. Thereafter KB was referred to a neurologist (PZ) for further evaluation. KB was first seen by PZ in August 2014.

During initial evaluation KB recalled a back injury when gardening in November 2013 resulting in reduced flexibility and back pain when bending. Symptoms persisted for months resolving prior to development of leg weakness. There were no issues with bulbar function, sensation, or upper extremity power. There was a question of gait in coordination but no leg muscle atrophy or spasm. Examination revealed normal appearance of limbs and skin without atrophy [4]. Motor examination revealed normal tone and power except for 4/5 hip flexion strength bilaterally. Reflexes were brisk (4/5) without clonus, but with an equivocal left Babinski sign. Sensory function, limb coordination, and gait were normal.

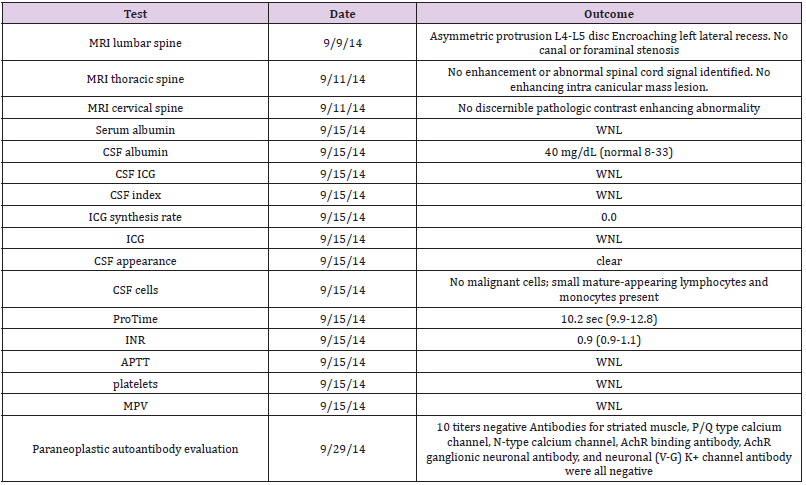

Table 1: Testing for myelopathy and paraneo plastic disease.

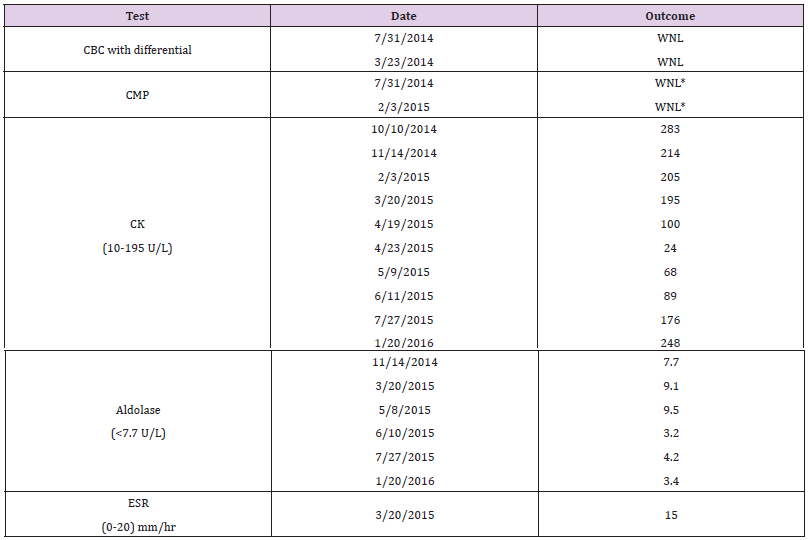

Table 2: Summary of laboratory measurements.

Myelopathy, lymphoma recurrence, MS, ALS, or paraneoplastic disorders were suspected, and lumbar puncture and MRIs of the full spine and brain (with and without contrast) were ordered along with the laboratory tests shown in (Table 1). Results of EMG testing performed by PZ on 10/16/14 were equivocal based upon bilateral borderline sural sensory conduction findings and a question of reduced motor recruitment in both the right vastus medialis and left extensor digitorum brevis unassociated with changes in motor unit configuration or spontaneous activity. Comprehensive metabolic panels ordered as part of regular semi-annual checkups in August 2014 and February 2015 was essentially normal except for an elevated serum creatinine (Table 2). However, a subsequent urinalysis was normal, and a cystatin C measurement of 0.89 mg/L resulted in an eGFR of 88 mL/min/BSA. A repeat of cystatin C measured on 2/03/15 was 0.98 mg/L which calculated to an eGFR of 77 mL/min/BSA.CBCs with differentials assessed in July 2014 and again in March 2015 were normal. CK and aldolase measurements were high or borderline high in October 2014, and remained high for several months (Table 2).

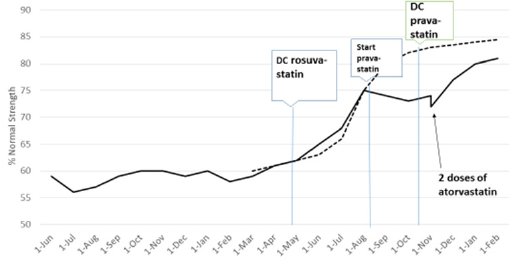

*serum creatinine was slightly elevated in July 2014 (1.29 mg/ dL) and again in February 2015 (1.34 mg/dL). The latter creatinine elevation coincided with an elevated CK. Numbers in parentheses denote reported normal range. A summary of the timeline of key events is in (Figure 1). A simple 2 X 2 contingency table was constructed that took account of a total of 16 measurements of CPK (10 measures) and aldolase (6 measures) when the patient was ON a statin or OFF a statin, and when either CPK or aldolase measurements were WNL or ONL (outside normal limits). There were 0 instances in which the patient had been ON a statin and WNL. There was 1 instance in which the patient had NOT been on a statin and was ONL. A Fisher exact p was calculated as p = 0.0009, suggesting a statistically significant relationship between statin use and out-of-range values for biomarker measures of myopathy. Statins have been shown to increase exercise-induced muscle injury [5].

After inflammatory disease, Myasthenia Gravis, recurrent lymphoma in the spine, brain pathology, and paraneoplastic disease had been ruled out; we considered the possibility of a drug-induced phenomenon. Among the drugs that KB had taken regularly monteleukast, rosuvastatin, and tadalafil all exhibit low propensities for muscle-related side effects including myalgia and weakness as reported in Lexicomp monographs [1]. Tadalafil related myalgias occur with a 2-14% frequency with the incidence of muscle weakness reported at less than 2% according to a postmarketing surveillance report [2]. Neuromuscular weakness associated with monteleukast is 2% [1].

A prior case has been reported in which the combined use of simvastatin and tadalafil produced myalgias and muscle weakness, and this outcome was explained on both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic bases [6]. Pharmacy kinetically, CYP3A4 inhibition by tadalafil presumably caused slower elimination and excess accumulation of simvastatin and increased simvastatininduced myalgia. Pharmacodynamically, it was noted that both drugs independently are capable of causing myopathy [6]. Doses of rosuvastatin and tadalafil had been taken concomitantly for several months by KB, however unlike simvastatin, rosuvastatin is metabolized principally by CYP2C9, rather than CYP3A4 and the extent of CYP2C9 inhibition by tadalafil would be weak-to-modest, and unlikely to lead to inhibitory drug-drug interaction based on its low [I]/Ki ratio [7]. On the other hand, tadalafil is unique among PDE5 inhibitors with regard to its ability to inhibit PDE11A1 [8], though PD11A may not be significantly expressed in skeletal muscle [9]. In the present case, however, abstention from tadalafil for several weeks produced essentially no remittance from muscle weakness. Another case of simvastatin myopathy characterized by pain with profound muscle weakness has also been reported in a 79 year old patient [10].

All statins are well known to cause myopathy that usually is expressed as myalgias with or without weakness with the overall prevalence of 7-29% among patients with minimal or no elevations of CPK [11,12]. The appearance of myopathy expressed solely or predominantly as weakness seems rare [12]. Moreover the STOMP study failed to find any evidence that atorvastatin altered muscle function [13]. Low levels of vitamin D have been associated with statin-related myalgia which tended to remit once vitamin D levels were restored to normal after supplementation [14]. However, KB had self-supplemented with vitamin D3 for many years, and his muscle weakness persisted even in the face of slightly elevated vitamin D levels. After ruling out the most obvious potential causes of KB’s myasthenia in light of his medical history, and considering the retrospective apparent temporal correlations between intermittent statin use, self-assessed degree of muscle weakness (with improvement occurring while off statins and symptoms recurring when re-challenged with statins), and elevation of biomarkers for muscle injury, we believe that this patient’s symptoms which he described primarily as muscle weakness were attributable to his use of statins. Whether symptoms were initially brought on through an interaction between rosuvastatin and tadalifil can’t be completely ruled out, but seems unlikely.

Some studies suggest that statin-induced myopathies may be due to decreases in mitochondrial function [12], however there is also evidence, particularly for individuals that have been taking statins for extended periods of time, that statins induce musculotoxic anti-HMGCoA antibodies, and that muscle recovery in these patients whose myopathy is immunologically mediated can be slow or incomplete [15,16]. In contrast, a recent analysis of ASCOT data suggests that statin myelopathic adverse effects are nothing more than a nocebo phenomenon [17-19]. The precise nature of KB’s pathology cannot be determined, since he has declined further testing.

Statin-induced myopathy commonly, but not always, presents as myalgia and cramping. Although it is a less common form of presentation, a statin-induced autoimmune myasthenia can occur in 2-3/100,000 statin users [16], and we concur with Dobkin [17] that statin use should be included in the differential diagnosis when myasthenia occurs in elderly patients who have a long history of statin use in spite of the possibility of a nocebo effect [19]. While holidays from statin use may provide remission, it should be noted that remission may be slow to develop (Figure 1) [4], and on average requires more than two months [18].This case also begs the question about how to manage primary or CVD in statin-intolerant patients. For KB we have decided to use the algorithm specified by The European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel [12].

Figure 1:Patient estimated self-assessment of muscle weakness over time. The dashed line is an approximation of the projected tensile strength recovery rate of skeletal muscle after injury along the lines of the description by Watson [4]. Callouts denote approximate dates of statin use or discontinuation. Only two doses of atorvastatin were taken before the patient reported a sudden setback in muscle weakness.