Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Elsayed AG*1, Adler W2 and Lebowicz Y1

Received: July 20, 2017; Published: August 02, 2017

Corresponding author: Ahmed Gamal Elsayed, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Edwards Comprehensive Cancer Center, Marshall University , Huntington, West Virginia. 1400 Hal Greer Boulevard, Huntington, WV 25701, USA

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000249

Objective: Disparities in cancer diagnosis, treatment and survival among different subgroups classified based on race, socioeconomic status and age have been previously noted. There is however a paucity of data addressing cancer disparities in rural populations. The purpose of this study is to examine multiple myeloma disease characteristics and survival in a rural population in comparison to their urban counterparts.

Methods: This is a retrospective analysis of 81 multiple myeloma patients who presented to a New Mexico local hospital and cancer center from 2003 to 2013. Patients were classified to either rural or urban based on the Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes (RUCA) version 2.0, Categorization D.

Results: Rural patients had longer duration of initial presenting symptom prior to diagnosis, suggesting that urban patients were more likely to seek medical attention earlier than their rural counterparts (p = 0.0037). Numerically, rural patients were more likely to be diagnosed at a more advanced disease stage (p = 0.063), while urban patients were more likely to be diagnosed at an asymptomatic stage. Patients in the rural group had a median survival of 39 months, while urban patients had a median survival of 69 months (p < 0.001). Log-rank test for equality of survivor function suggested a survival benefit in favor of the urban group.

Conclusion: Rural patients with multiple myeloma had shorter survival compared to their urban counterparts. The worse outcome of the rural patients is likely a result of diverse challenges that impact health care in rural populations. It is recommended to encourage efforts aiming to enhance health care services in rural areas, in order to minimize the disparities between rural and urban populations.

Keywords: Health disparities; Cancer Disparities; Rural Health; Myeloma Survival

Multiple myeloma (MM) is estimated to account for 0.8% of all cancer cases worldwide. Approximately 47,000 males and 39,000 females are diagnosed with Multiple Myeloma annually [1]. Multiple Myeloma accounts for 0.9% of all cancer deaths; approximately 63,000 death annually worldwide. Incidence of multiple myeloma is higher in males compared to females [2]. The pathogenesis of multiple myeloma is a complex process leading to malignant replication of a plasma cell clone with secretion of a monoclonal protein causing multiple organ dysfunction. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance(MGUS) consistently preceded the diagnosis of multiple myeloma [3]. MGUS progresses to myeloma or a related malignancy at a rate of 1 percent per year [4].

Many studies have examined the epidemiology, clinical features, treatments and outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma, but few studies comment on disease characteristics related to rural residence. An epidemiologic study done in Burgundy, France with a population of 478,000 over a 7 year period reported a slightly higher risk of multiple myeloma in urban areas compared to rural areas, but the difference was not statistically significant [5]. Another study done in Arkansas reported that being born and raised in a rural area is associated with high risk for multiple myeloma [6], while an Iranian study reported a lower incidence of multiple myeloma in rural areas in Golestan, Iran [7]. A 25 year survey from 1950 to 1975 done by Blattner et al reported a two to three fold increase in MM mortality during this period. The increase was greater in nonwhites than whites. The increase was found to be uniform in urban and rural populations [8].

A more recent Australian study that examined the likelihood of accepting autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in newly diagnosed transplant-eligible MM patients, reported that patients from rural locations were as likely to proceed to ASCT as those from metropolitan locations. The authors commented that the acceptability of rural patients to ASCT may have been related to universal free health care access and strong clinical links between nonurban clinics and tertiary referral centers [9].

Medical records from Memorial Medical Center (MMC) and the MMC Cancer Center (MMCCC) were searched for all patients with history of multiple myeloma who were admitted to the hospital regardless of the reason for admission, or seen at or reported to the Cancer Center from January 2003 to December 2013. A total of 87 patients were found to meet these criteria. A total of six patients were excluded. Four patients were excluded because sufficient evidence to establish the diagnosis could not be verified. The other two patients had solitary plasmacytomas with no evidence of systemic involvement. Study flowchart is shown in (Figure 1). Data collected included demographic information, chief presenting symptoms at initial diagnosis and duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis, smoking pack-year index, type of immunoglobulin, and initial laboratory and clinical features of the disease at the time of diagnosis. The charts were examined for evidence of offering or discussing Autologous Stem Cell Transplant (ASCT) as a treatment option, and whether ASCT was actually performed at any point during the disease course. Patient staging at diagnosis according to International Staging System (ISS) for myeloma was determined, if possible. Data was collected from cancer center medical records for patients who received treatment there or transferred care to it after admission. For patients who didn’t receive treatment at MMCCC, data was collected from hospital chart and records from primary oncologist included with admission chart if available.

Figure 1:Study flowchart.

The US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA) were used to classify patients to rural and Urban. RUCA is a census tract-based classification scheme that utilizes the standard census bureau urban definition in combination with work commuting information. Categorization D of RUCA was chosen for our study. It defines urban as all places that have 30% or more of their workers going to a Census Bureau-defined Urbanized Area. Patients were classified based on their residence at the time of diagnosis to rural (29 patients) and Urban (52 patients) according to categorization D of RUCA version 2.0 [10].

Bivariate analysis was conducted to look for baseline differences among the rural and urban groups. Tests for normalization were performed on continuous variables to search for transformation that would normalize the variable. T-test methods were then applied to these variables. A search for a transformation in the ladder of powers (Tukey 1977) including: cubic, square, square root, log, 1/(square root), inverse, 1/square, and 1/cubic was performed on calcium, haemoglobin and creatinine. Only the inverse of creatinine was considered. Fisher exact tests were done on categorical variables to look for differences between rural and urban group. To compare overall survival among the two groups, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test for trend were performed. Cox proportional hazard models adjusting for significant baseline differences were also analyzed. Stata/SE 13.1 for Windows software (College Station TX) was used in the analysis.

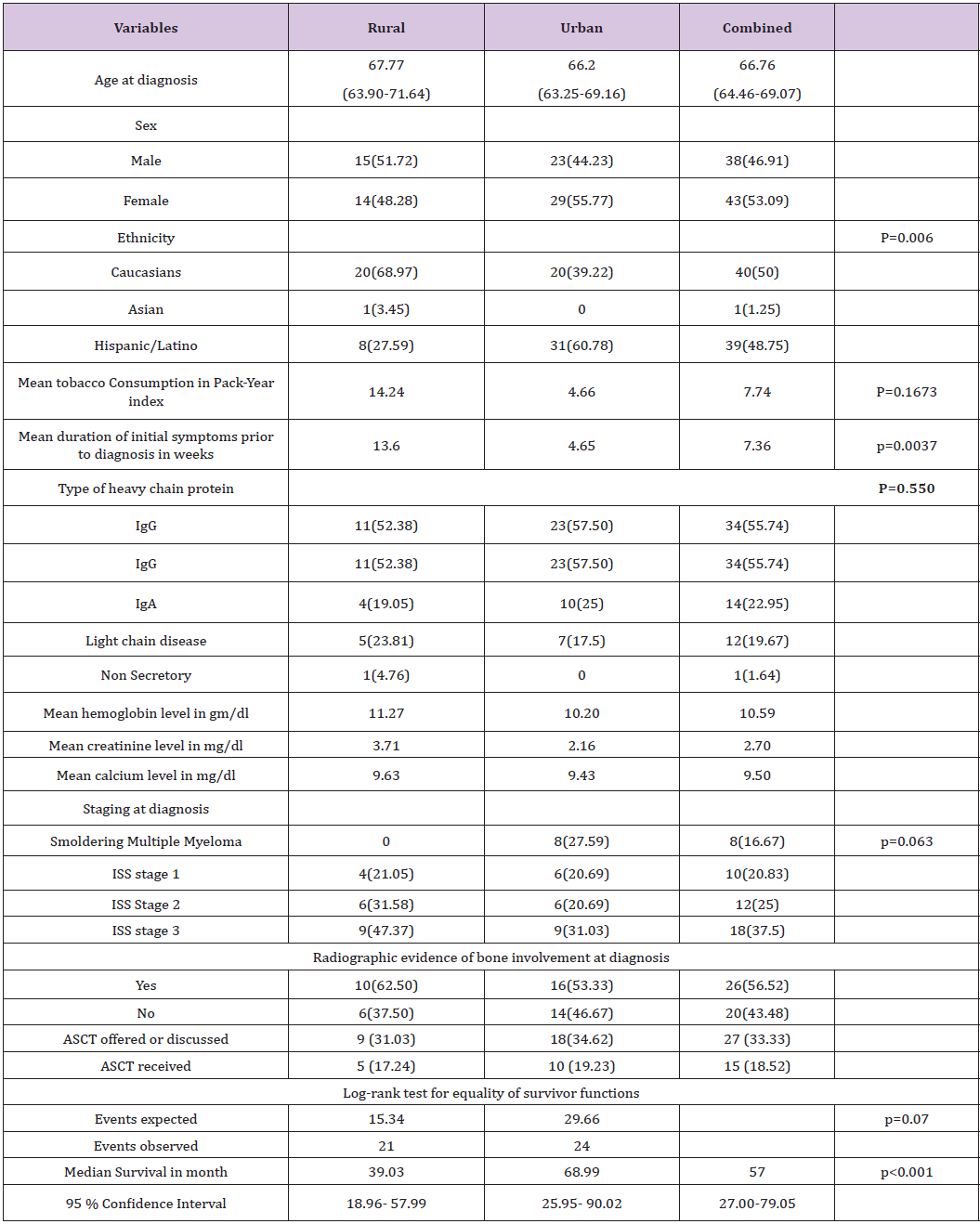

The type of heavy chain protein was generally similar for both groups. 55.74 % of patients diagnosed with Immunoglobulin G heavy chain disease. Eleven out of 21 patients (52.38%) in the rural group (where there is documentation of type of heavy chain protein) had Immunoglobulin G type, while in the urban group 23 of 40 (57.5%) patients were of Immunoglobulin G type. Patients in the rural group were more likely to have a longer duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis. Five patients in the urban group were diagnosed while still asymptomatic in a routine checkup or because of an abnormal lab values, while all patients in the rural group (where data were found in chart about the nature of their presenting problem) were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis. The average duration of initial presenting symptom prior to diagnosis was 7.36 weeks for the whole sample, 13.6 weeks for the rural group, and 4.56 weeks for the urban group (Table 1). These findings suggest that urban patients were more likely to seek medical attention sooner than their rural counterparts (P-value = 0.0037).

Table 1:Baseline characteristics and survival outcome.

Tobacco consumption was higher among patients in the rural group compared to the urban group. Rural patients on average had a smoking history of 14.2 pack-years, while urban patients had a 4.6 pack-years history. This finding, however was not statistically significant. (P-value= 0.1673). Analysis of multiple myeloma staging data in both groups revealed that 8 out of 29 subjects in the urban group, where it was possible to determine stage at diagnosis, were diagnosed with smoldering myeloma while all of the 19 subjects in the rural group, where it was possible to determine stage at diagnosis, were diagnosed at a more advanced stage. Nine out of the 19 patients in the rural group were at ISS stage 3 at the time of diagnosis (47.37%), while nine out of 29 in the urban group were at the same stage (31.03%). Data suggests that rural patients were diagnosed at a more advanced disease stage, while many urban patients were diagnosed at smoldering myeloma stage (p=0.063). Radiographic evidence of bone involvement was present in 56.5 % of patients at diagnosis. The finding was comparable in both groups with 62.5 % of the patients in rural group having radiographic evidence of bone involvement at diagnosis and 53.33% in the urban group.

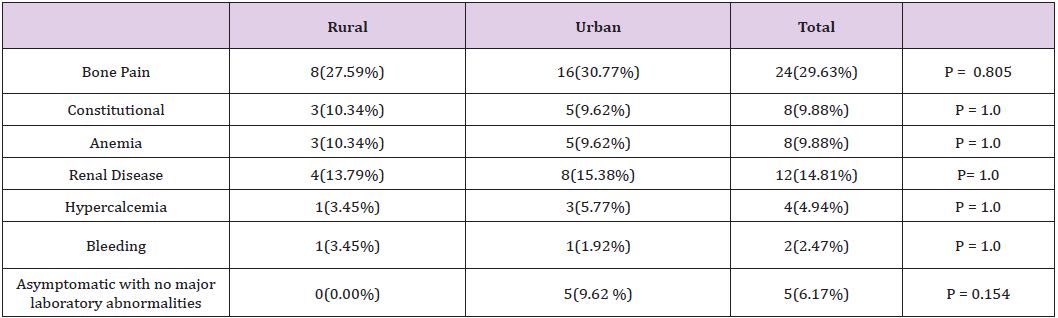

The nature of the chief presenting problem was compared in both groups. Bone pain was among the chief presenting symptoms in 27.6 % of patient in the rural group and 30.8% of the urban group. Renal disease was reported at presentation in 13.8% of the rural patients and 15.4% of the urban patients. Interestingly, 9.6% of the urban patients presented at an asymptomatic stage, while all rural patients (where data were found in chart about the nature of presenting problem) were symptomatic at presentation. The initial finding triggering further work up in the asymptomatic group was abnormal protein levels. Overall, the nature of the chief presenting problem was generally similar in both groups with the exception of the higher likelihood of patients in the urban group to be diagnosed at an asymptomatic stage. Table 2 summarizes these findings.

Table 2:Nature of the presenting problem.

Patient charts were reviewed for documentation of ASCT being offered or discussed as a treatment option and for evidence that patients actually received the transplant. Nine rural patients out of the 29 (31%) had evidence on record that ASCT was offered or discussed with them. In the urban group, 18 patients out of 52 (34.6%) had such finding. Ten patients out of the 18 in the urban group (19.2% of the entire urban group) who were offered ASCT actually received the transplant, and five out of nine patients in the rural group offered ASCT (17.2% of the whole rural group) had evidence in their medical records of actually receiving it. In the whole sample, 33.33% of patients had evidence of being offered or educated about ASCT and 18.5% of patients actually received the therapy. The reasons for not receiving ASCT after being offered or discussed included patient refusal, postponement to a later point in the disease course, financial reasons, and rejection by the transplant center because of co-morbidities. These findings reflect that there was no difference between rural and urban patients with regard to offering or receiving ASCT.

For survival analysis purpose, one patient of the urban group was excluded because length of time subject remained alive after diagnosis was unconfirmed. Another patient in the urban group was lost to follow-up and the subject’s survival was censored based on last known follow-up. Two out of the eight urban patients with smoldering myeloma were excluded as they never progressed to multiple myeloma. The other six patients were included in the analysis after setting their start point as the date when they were deemed to have progressed to multiple myeloma. A total of 49 patients in urban group and 29 patients in rural group were included in the analysis. Time of survival was considered to be from time of diagnosis of symptomatic multiple myeloma till date of death or May of 2014, when analysis was run.

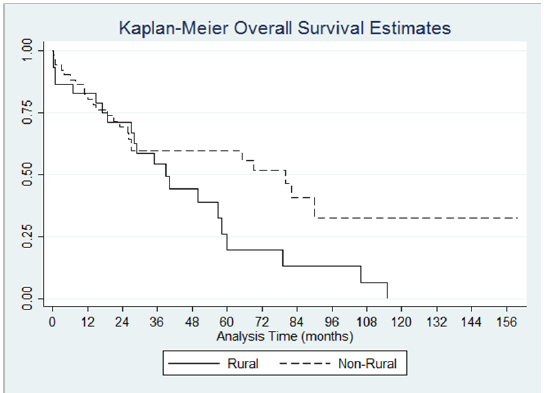

Median survival time for the whole sample was 57 months. Patients in the rural group had a median survival time of 39 months (95% CI 18.96 - 57.99). Patients in the urban group had a median survival time of 69 months (95% CI 25.95-90.02). Kaplan Meier curve for the analysis is shown in (Figure 2). Log-rank test for equality of survivor functions was performed and showed difference in survival in favor of the urban group. Twenty one events were observed in the rural group while the expected events were 15.34. In the urban group, 29.66 events were expected while only 24 events were observed. (p=0.07) The baseline difference in ethnicity and duration of initial symptoms among the two groups was statistically significant. Adjustment for both variables in the Cox proportional analysis showed no significance.

Figure 2:Kaplan-Meier Overall Survival Estimates p<0.001.

This is the first US based study that examines rural-urban difference in survival of multiple myeloma patients. The study findings reflect that multiple myeloma patients who resided at a rural area at the time of diagnosis had shorter survival compared to their urban counterparts. Many factors might have contributed to this outcome. Rural patients had longer duration of initial symptoms prior to seeking medical attention. This is perhaps a result of multiple challenges that face health care in rural areas. The lack of medical providers in rural areas is an established finding that is well recognized by many surveys and governmental reports. About 20% of the US population lives in rural areas, yet only 9% of physician practice in rural areas [11]. Although some growth has occurred over the last decade in the rural health care system, many rural population health care needs are still unmet. An analysis of national data concluded that rural residents are less likely to obtain certain preventive health services than urban residents. The same analysis reported that rural residents were far behind urban residents in meeting the goals set by the national health promotion and disease prevention initiative Healthy People [12]. Another retrospective analysis of Medicare beneficiaries reported that rural residents have less overall utilization of medical providers compared to urban residents. The study showed that rural residents have increased travel distance and time to seek medical attention when compared with urban residents [13]. Another major challenge in the delivery of health care to rural populations is the lack of insurance or underinsurance, which is reported to be more prevalent in the rural populations [14].

The study data suggests that rural patients are more likely to be diagnosed in a more advanced stage compared to urban patients. These findings are consistent with other studies comparing stage at diagnosis between rural and urban patients with different cancers [15-17]. In the study sample, rural patients displayed a trend towards increased tobacco consumption. These results are consistent with other reports that noted significantly increased smoking among adults and adolescents in rural counties when compared to urban counties [18].

Multiple studies have been conducted which address the effect of geographical distance to transplant centers and survival after bone marrow transplant [19,20]. Other studies commented on the impact of rurality on survival after ASCT. A US based study reported worse survival in rural patients who underwent ASCT. The study reported that rural patients had at least a 5% lower probability of survival at 1 year and 5 years after ASCT [21]. This study did not comment on the accessibility of ASCT to rural patients, however. A more recent Canadian study showed no difference in post transplant survival between rural and urban patients [22]. The lack of health insurance in rural America was suggested as a contributing factor to the worse outcome reported in the American study. In contrast, the transplant cost in the rural Canadian population is fully covered by universal health care whenever patients are deemed eligible. The same study also showed that rural patients with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma had lower probability of getting a bone marrow transplant compared to urban patients. The results however, were not statistically significant. A British study that enrolled 23,910 incident cases of acute myeloid leukaemia, from 1998 to 2007 reported that generally patients with lower socioeconomic status, regardless of their geographical location were less likely to receive bone marrow transplantion [23].

The analysis shows no difference between the two groups in regard to ASCT accessibility. Rural and urban patients were both offered or educated about ASCT as a treatment option. Patients in both groups had a similar chance of receiving ASCT during the course of their disease. It is important however to understand that in southern New Mexico, distance to a transplant center is similar for rural and urban patients. Therefore, results might not be representative of ASCT accessibility in rural populations nationwide. In the whole sample, 33.3% of patients had evidence of being offered or educated about ASCT and 18.5% of patients actually receiving it. These findings are comparable with other national studies. In a cohort of 1027 patients from 1985 to 1998 at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, 10% of patients did receive ASCT at some point in their disease course [24]. A more recent study done at the Mayo Clinic included 1038 patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma between 2001 and 2010, reported that 393 patients (37%) received ASCT at some point in the course of their disease [25].

Multiple Myeloma is preceded by Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS). In a retrospective study by Bianchi et al, optimal follow-up of MGUS patients led to higher detection rate for smoldering multiple myeloma. Subsequently, patients diagnosed at the stage of smoldering myeloma were less likely to have multiple myeloma-related complications at the time of diagnosis. Although results were not statistically significant and no survival benefit was found in the optimal follow-up group, the study suggested that early diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma before the onset of severe renal and skeletal complications is beneficial and at least should decrease disease morbidity [26].

In another retrospective study by Kariyawasan et al. [26], a prolonged time to diagnosis had a statistically significant effect on disease free survival. The study showed that a delay in diagnosing multiple myeloma has a significant impact on the clinical course of the disease, and is likely to cause more discomfort for patients and perhaps complicate their care. The study however did not show an impact on survival as it was underpowered for that [27]. Multiple myeloma is not a curable disease and there is no known intervention that can delay the progression of MGUS to symptomatic myeloma. However, it is believed that with the introduction of new more effective therapeutic interventions in the last decade, there is the potential for impact on survival with early detection of myeloma. Avoidance of extensive bone involvement and irreversible renal damage will not only improve quality of life but may also have a favorable effect on health care expenses. Large prospective studies are required to demonstrate benefit of early diagnosis and treatment on survival.

Early diagnosis and referral of multiple myeloma patients in rural population will have a favorable impact on quality of life and on health care cost. It is also possible that early diagnosis and treatment may translate to a benefit in survival. In order to achieve this goal, efforts to enhance health care infrastructure in rural areas must continue. Recruiting more health care providers, encouraging rural residents to seek medical attention and creating policies to increase health insurance prevalence among rural population are important steps. Health care providers in rural areas should consider MM in patients presenting with anemia, hypercalcemia, renal failure or bone pain. Appropriate clinical and laboratory evaluation and referral should not be delayed.

Authors agree with the studies recommending that rural patients should proceed to ASCT when deemed eligible and are agreeable to this treatment [20,22]. The worse outcome of rural populations after transplant that was suggested by Rao et al. [21] can be ameliorated by following a comprehensive post transplant care plan. Patients should have close follow-up with a transplant center. The transplant physician should coordinate care with the patient’s local oncologist and primary health care provider. The study is limited by relatively small sample size. The small sample size limits the ability to produce statistically significant results in some of the patients and disease characteristics analysis. The study represents single institution experience. Results are based on enrollment of patients who eventually made it to MMC and its associated cancer center. Outcomes of other patients who presented to nearby rural hospitals and rural primary care providers and were never enrolled in this study are unknown.