Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Pınar Öztürk1, Gönül Vural2*, Mehmet Öztürk3 and Şadiye Gümüşyayla2

Received: January 20, 2018; Published: February 08, 2018

Corresponding author: Gönül Vural, Yildirim Beyazit University, Medical Faculty, Department of Neurology, Ankara 06800, Turkey

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000742

Purpose: This study aims to evaluate the quality of life in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients and investigate the relationship between pain, sleep quality, fatigue and mood disorders with disability and quality of life.

Material and metods: 50 MS patients and 50 healthy volunteers participated in this study. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and McGill Pain Index, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), SF-36 quality of life scale, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) were used.

Results: The SF-36 scores were significantly lower, andthe BDI, FIS and PSQI score swere significantly higher in the MS patients when compared to the healthy volunteers. The results showed that fatigue, depressive moods, impaired sleep quality and severity of pain had a significant effect on quality of life. The increments in the EDSS scores were correlated with fatigue and depressive moods, while no such correlation was shown with sleep disorder orseverity of pain.

Conclusion: Conclusion: Our findings suggest that MS patients experience poors leep quality, are more depressive, and often suffer from fatigue and pain. Accordingly, physicians should inquire about such parameters as fatigue, pain, depression and sleep disorders that lower the quality of life in patients and render them more disabled, and should use practical test batteries to objectively evaluate and cover these factors in their treatment strategy

Keywords: multiple sclerosis; Fatigue; Pain; sleep quality; Depression; Quality Of Life; Disability

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory, immune- mediated demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. It causes physical and neurocognitive chronic disability. It is the most common cause of non-traumatic disability in young adults. MS, which is a progressive disease of the CNS, involves a dynamic process. The assessment of disability throughout the disease is of crucial importance, particularly regarding treatment planning. The evaluation of disability becomes quite a complicated task when physical, psychological, cognitive and social aspects of the disease are considered. While there are numerous scales developed for this purpose, the Expanded Disability Status Scale - EDSS is the most commonly used one in evaluating MS patients. However, this scale is far from being able to measure some of the important causes of disability, such as cognitive functions, sleep disorders, fatigue, pain, behavioural problems and psychological breakdown in MS patients [1,2]. This study was designed to investigate the pain, sleep quality, fatigue and mood disorders that are outside the scope of the scales we frequently use to assess disability in practice in MS patients, but which have significant impacts on the quality of life of the patient.

The study included 50 patients who admitted at Yildirim Beyazit University Faculty of Medicine Neurology Outpatient Clinic sequentially, and who were definitively diagnosed with MS according to the Revised McDonald Criteria and were being followed up by us, as well as 50 healthy subjects who matched the patient group in terms of age and gender. Those who had other neurological and psychological disorders that could cause sleep disorder, those with systemic diseases that can cause pain or who had experienced an attack in the past three months, and those who routinely took analgesics or drugs that can affect sleep were excluded. Approval from the ethics committee and participants'written consents was obtained.

The study was designed to be descriptive. Sociodemographic and clinical information pertaining to the patients was recorded. Each patient went through an extensive neurological examination and their Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores were determined. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) was used to evaluate the functional capacity of patients. The Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS) and McGill Pain Index were used to determine the localization of pain, pain type and severity. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), SF-36 quality of life scale, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) were completed for both patients and healthy subjects.

The data obtained was analyzed using a statistical package program (SPSS) (Version 17, Chicago IL, USA). Descriptive statistics (mean±standard deviation, minimum, maximum, frequency distribution and percentile) are provided in the study for categorical and continuous variables. Association between variables was evaluated using Spearman's Correlation Analysis. The statistical significance level was accepted to be p<0.05.

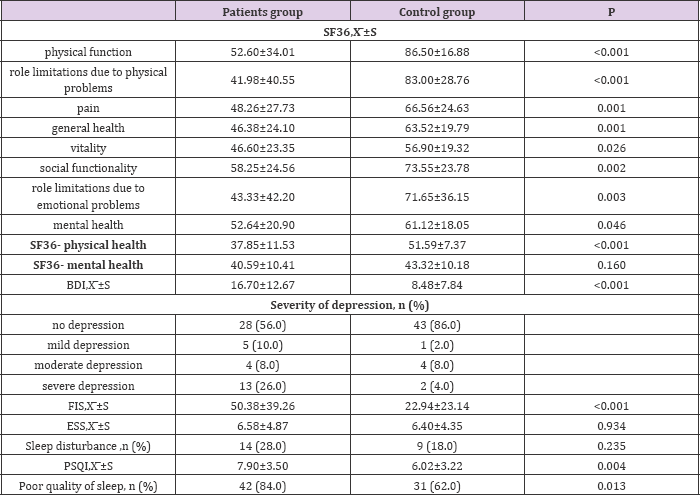

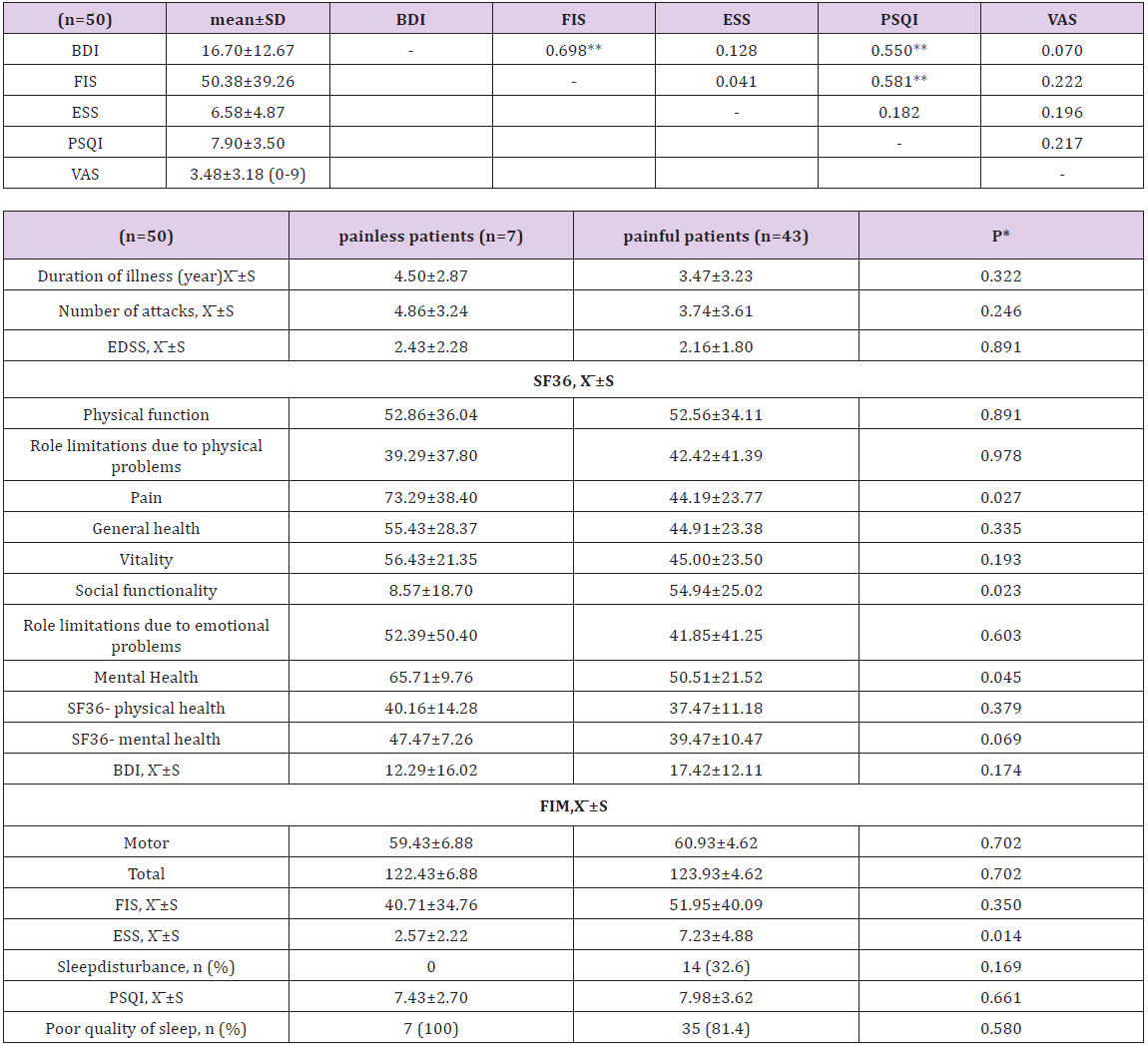

The patients and healthy volunteers included in this study consisted of both females (68%) and males (32%). The mean age was 33.72±9.88 in the patient group, and 29.72±8.67 in the healthy volunteer groups. The patient and control groups were comparable in terms of age and sex. Table 1 presents the clinical features of the patients. Mean FIS scores of MS patients were significantly higher than healthy controls (p<0.05). SF-36 physical function, role limitations due to physical problems, pain, general health, vitality, social functionality, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health factor scores and physical health main factor score of MS patients were determined to be significantly lower than those of the healthy individuals in the control group (p<0.05). BDI scores were also significantly higher in MS patients (p<0.05). According to the results of the BDI, depression was present in 44% of the patient group whereas this rate was 14% in the control group. The percentage of patients with severe depression (26%) among MS patients was significantly higher than the healthy subjects (4%) in the control group (p <0.05).When daytime sleepiness was evaluated using the ESS, 28% in the patient group had daytime sleepiness, while 18% had it in the control group; however, this was not found to be statistically significant. Evaluation of night time sleep quality showed a significantly higher PSQI scores in MS patients compared with healthy individuals and it was pathological in 84% of the patients (p<0.05) (Table 2). The relationship between disease duration, the total number of attacks, EDSS score, SF-36 and function alin dependence and mood, fatigue, sleep disorder and pain severity was examined in MS patients.

Table 1: Clinical features of MS patients

Table 2: Mean scores of fatigue, depression, daytime sleepiness, nighttime sleep quality and SF SF-36.

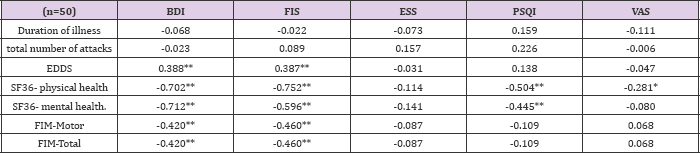

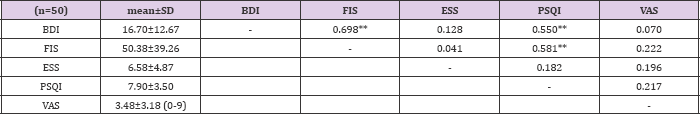

A significant negative correlation was identified between the quality of life and fatigue, depression, poor sleep quality and severity of pain. However, increased EDSS and decreased function alin dependence were associated with fatigue and depression, but not with poor sleep quality or pain. No significant correlation was identified between disease duration and the number of attacks and mood, fatigue, pain and sleep quality (Table 3). The presence of fatigue and depression were positively correlated in MS patients, and an increase in both BDI and FIS was associated with an increase in the patient's PSQI score, which is associated with the additional presence of poor night time sleep quality in depressive or fatigued patients (Table 4). Of the MS patients, 86% (n=43) suffered from pain. When pain localization, type and severity of these 43 patients were reviewed, it was determined that 58.1% had pain in the head region, 37.2% had it in the upper extremities and 32.6% in the lower extremities. Pain type was continuous/steady/constant in 23.3%, rhythmic/periodic/intermittent in 44.2% and brief/momentary/ transient in 32.6%. Pain severity was mild in 18.6%, discomforting in 65.1%, horrible in 7% and excruciating in 9.3%. Of the patients examined, 60% had neuropathic pain, 76% had nociceptive pain, and 16% had mixed pain and 46% pain induced due to treatment. Mean VAS score of the patients was 3.48±3.18 (min: 0 - max: 9). The VAS score of those MS patients who had nociceptive sub-type pain was significantly higher than those who did not have such pain (p<0.05). A statistically significant difference was noted between the MS patients who had pain and those who did not have pain in terms of SF-36 pain and social functionality factors and ESS score (p<0.05). While the ESS score of the MS patients who had pain was significantly higher than in those who did not have pain, their SF- 36 pain and social functionality scores were significantly lower. Of those patients who suffered from pain, 32% had a sleep disorder. The ESS scores of the MS patients who did not complain of pain were within normal ranges and they did not suffer from a sleep disorder (Table5).

Table 3: Relationship between disease duration, the total number of attacks, EDSS score, SF-36 and functional independence and mood, fatigue, sleep disorder and pain severity.

Table 4: Relationship between BDI, FIS, ESS, PSQI and VAS.

Table 5: EDSS, SF-36, Function alin dependence, quality of sleep, sleepiness, depression and fatigue in MS patients with and without pain.

This study, in which we investigated the impact of multiple sclerosis on patients has revealed that the quality of life has deteriorated in these patients, that they are more depressed, frequently feel fatigued, lead a painful life and that their quality of sleep has deteriorated as well. Inaddition, a significant correlation was also determined between depression, fatigue and impaired night time sleep quality. Psychiatric disorders are commonly encountered during the course of MS. Depression is the most common one [3,4]. Levels of depression identified and reported in MS patients range from depression symptoms to major depression [5]. We identified 44% of our patients to be suffering from depression; with it being severe in 26% of those, moderate in 8% and mild in 10% of patients. According to the studies conducted with MS patients, lifelong prevalence of major depression ranges from 22.8% to 54%. It is also reported that compared to those suffering from other chronic diseases that cause physical disability, depression is more frequently encountered in MS patients [6]. This may be due to daily life hardships that are intensified due to disability, a feeling of psychosocial helplessness, desperation, the notion that "nobody understands me" and, alongside physical dependency, it may also be a manifestation of deteriorated cerebral functions due to the nature of the disease [7]. The presence of depression showed an association with fatigue and deterioration in night time sleep quality, an increase in EDSS scores, and a decrease in functional independence and quality of life. Depression symptoms increase fatigue either directly or through psychological impact. Also, fatigue could be considered as a symptom of depression [8]. We also observed a positive correlation in our study between depression and fatigue in MS patients. Those patients who were identified as suffering from depression according to BDI had higher levels of fatigue according to FIS. In the study conducted by Roelcke et al., a significant correlation was observed between depression and fatigue as well [9].

Although its cause is not fully elucidated, fatigue is one of the most serious symptoms observed in MS patients. While the definition may vary, the most commonly used definition is "a feeling of lack of energy and physical tiredness distinct from weakness". We also found a statistically significant difference in our study when comparing MS patients with healthy controls in terms of fatigue. It is also reported in the literature that more than 75% of patients display signs of fatigue [10]. Analgesics, anti spasticity drugs, sedatives, anticonvulsants and interferons used in the treatment of patients can also cause fatigue as a side effect [11]. This affects both the daily and professional lives of patients, and in turn, increases the risk of depression in patients with fatigue. Well, of course, the quality of life will also be affected negatively. In our study, we noted a negative effect in all subgroups of the SF- 36 quality of life scale for those MS patients with high FIS scores. Sleep disorders are also more commonly seen in MS patients compared to a healthy population and it is reported that it affects approximately 24% - 54% of patients [12,13].While quality of sleep can deteriorate secondary to immobility, spasticity and sphincter problems, it can also manifest as a primary problem as a result of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which impacts sleep-wake cycle, being affected by the disease [14,15]. In our study, while no statistically significant difference was noted in terms of ESS between MS patients and healthy controls, a statistically significant difference was noted in PSQI results. ESS is a scale that evaluates sleepiness, whereas PSQI is a scale that evaluates quality of sleep. Regarding the patients we evaluated, we noted deterioration in their quality of sleep rather than an increase in their overall daytime sleepiness levels. It may be difficult to make distinctions in the relationship between sleepiness and fatigue because deterioration in quality of sleep may lead to daytime fatigue or naps [16]. Similar to such circumstances, in our study according to PSQI those who suffered from sleep disorder were also more fatigued.

It should not come as a surprise that a sleep disorder naturally leads to deterioration in a patient's quality of life. In our study we found the low scores in patients’ SF-36 to be associated with poor quality of sleep.

There were significant differences between MS patients and the healthy individuals in the control group with regard to SF-36 physical function, role limitations due to physical problems, pain, general health, vitality, social functionality, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health factor scores and physical health main factor score. Since MS is a progressive chronic disease and such patients have a multitude of additional problems, it is rather an expected result for quality of life to be negatively impacted in such patients. Henriksson et al., in the study they conducted, indicated a strong impact on the severity of the disease and quality of life [17]. In a study conducted on 103 MS patients, the effects of depression and fatigue on the quality of life were investigated and in conclusion, it was stated that depression, disability and fatigue are independent factors negatively affecting the quality of life [18]. In a similar fashion, in our study, a negative correlation was observed between BDI and FIS, and all subgroups of the SF-36 scale. While pain, which affects daily activities and quality of life, is commonly seen in the advanced stages of MS, a chronic disease, in some patients it may be the initial symptom [19]. Numerous classifications can be done for pain. We investigated pain under four main groups; neuropathic pain, nociceptive pain, mixed pain and pain induced due to treatment. 60% of the patients had neuropathic pain, 76% had nociceptive pain, 16% had mixed type pain and 46% had treatment-induced pain. VAS scores were higher in patients who had nociceptive pain.

According to the McGill pain scale, 86% of the MS patients had pain. Most often the pain was in the form of a headache and it was usually rhythmic. In many of the patients, it was at a discomforting level. Studies investigating MS disease and headaches revealed that headaches occur in MS patients three times more often than in the normal population [20]. While our patients mostly indicated that the pain was localized in the head region, leg pain is the most frequently identified kind in the literature [21]. SF-36 pain and social functionality factors were significantly higher in those patients who had no pain. It was argued that pain and depression are directly and indirectly associated with fatigue and that a sleep disorder is the indirect effect [22]. Using ESS, we established a sleep disorder in those patients who suffered from pain. In a study done by O'Connor et al., pain was determined to be associated with fatigue [23]. We could not establish a significant relationship between pain and fatigue. While the life expectancy of MS patients is similar to that of the normal population, patients sometimes lead a partially dependent or fully dependent life physically and functionally. This disability is what underlines the importance of this disease. Although it has certain limitations, the EDSS has become an indispensible scale in monitoring the progression of the disease. The EDSS is useful in identifying disability, but it has its own limitations. The most commonly acknowledged current definition of benign MS requires an EDSS score of 3.0 or lower, and this precisely defines an ambulatory patient; meaning, a patient with a low EDSS score does not have an apparent disability. However, as set forth in a series of studies, which we also mentioned above, cognitive disabilities, fatigue, sleep and behavioural disorders, depression and deterioration in quality of life is established in MS patients, and even in the early stages. This in turn shows that EDSS scoring overlooks some of the functional effects caused by the disease.

In conclusion, this study revealed that sleep quality, social functionality and the quality of life are impaired, and patients feel more depressed and often suffer fatigue and pain, even at low EDSS levels, which points to low disability. Accordingly, a deliberate effort should be made to inquire about such factors as fatigue, pain, depression, social functionality, sleep disorders and cognitive impairment, as these may not be reflected in EDSS scores, but mayhave a negative effect on patients in terms of functionality, and replies to such in quiries should be assessed objectively using practical test batteries and included in treatment plans.

All authors make important and valuable contributions all steps of this article such as conception and design of the study, acquisition and interpretation of data, revising content and final approval.