Abstract

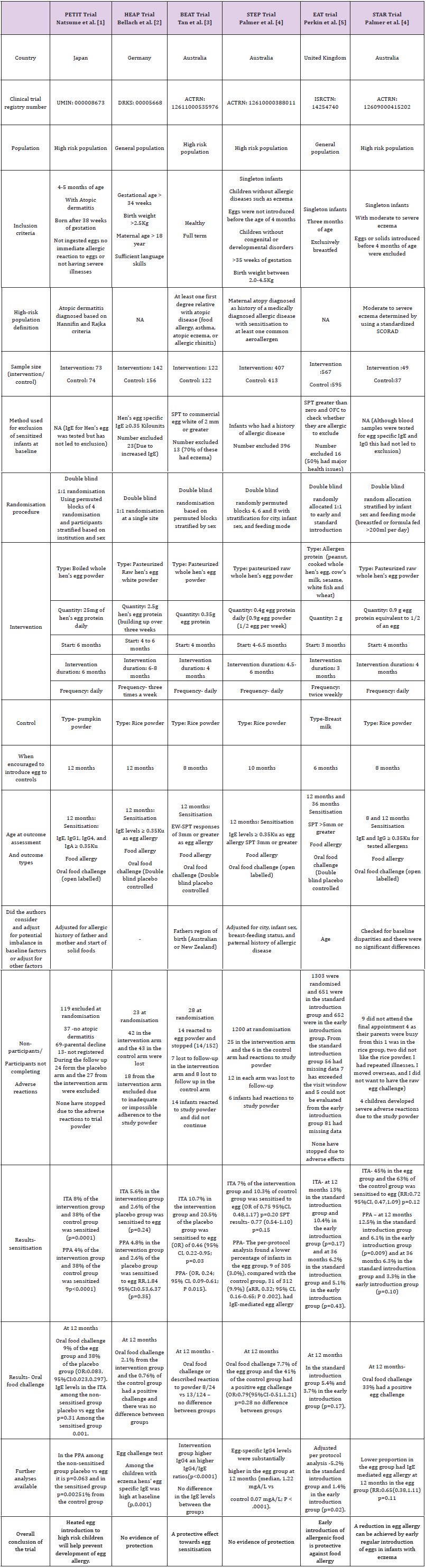

We refer to the six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (PETIT; Natsume et al, HEAP; Bellach et al, BEAT; Tan et al and STEP; Palmer et al, EAT; Perkin et al, STAR; Palmer et al, published within the last five years. These trials reported on early egg introduction and risk of later egg sensitization and egg allergy at 12 months of age. Based on these trial results, it is clear that RCT results need to be critically appraised and interpreted. We found that the methodological differences among the studies may have influenced the study results. Therefore, critical interpretation of RCT results is required to understand the evidence.

Keywords: Randomised controlled trials; Egg; Sensitisation; Allergy

Introduction

We refer to the six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) PETIT; Natsume et al. [1], HEAP; Bellach et al. [2], BEAT; Tan et al. [3] and STEP; Palmer et al. [4], EAT; Perkin et al. [5], STAR; Palmer et al. [6] published within the last five years. The trials reported on early egg introduction and risk of later egg sensitisation and allergy at 12 months of age. Although these six trials were very similar in several respects, we have concerns regarding the consistency of the findings. The Japanese PETIT trial was the only one to find a protective effect for egg allergy diagnosed using oral food challenge testing (OFC). Although the EAT and STAR trials concluded that early introduction of egg was protective against food allergy, neither showed good evidence on OFC testing. In terms of sensitisation, the BEAT trial found reduced sensitisation when whole egg was introduced to high risk infants. The STEP and HEAP found no protection for either sensitisation or food allergy.

RCTs provide the highest level of evidence for a causal effect from an intervention [7]. However, belief in the RCT as a study design may lead to the results being accepted as unarguable evidence and a failure to critically appraise individual studies. This can lead to confusion when similar RCTs present conflicting results as is the case here. There are several methodological differences between the studies which may have influenced the results. PETIT was based on high risk children in Japan. The other studies on high allergy risk populations, the BEAT, STEP and STAR, all used Australian birth cohorts, and the allergy risk was defined differently. In the BEAT study, high risk was defined as any immediate family member (father, mother, older sibs) with food allergy, asthma, atopic eczema or allergic rhinitis. In STEP it was based on the “atopic status” of the mother only (medically diagnosed allergic disease with sensitisation to at least one common aero allergen), and results were adjusted for paternal allergic disease. The STAR trial recruited babies with severe eczema. In all three trials the intervention was similar (whole egg) and, all assessed the outcome at 12 months. However, the intervention timing and duration differed. In STAR and BEAT the intervention began at 4 and ended at 8 months with a duration of 4 months. In STEP, the intervention began at 4.5- 6 months continuing until 10 months with a variable duration of 4.5-6 months. They also differed with respect to analysis. Although both BEAT and STEP provided an intention-to-treat analysis, STEP adjusted for baseline factors which appeared different between the groups while BEAT controlled only for region of origin of parents. All 3 trials may have been underpowered (Table 1). The STEP trial which reportedly failed to reach the planned sample size was almost twice the sample size of BEAT and 10 times the size of STAR.

In contrast, the HEAP and EAT trials were selected from the general population. The intervention in HEAP was egg white, as opposed to whole egg, and in EAT it was a combination of 6 allergenic foods, making it distinctly different from all the other trials. In HEAP egg introduction commenced at 4-6 months and continued until 12 months of age with an intervention duration of 6-8 months, substantially longer than the other trials, and extending into a different developmental period of infancy (12 months as opposed to 8 or 10 months in BEAT and STEP and 4 to 8 months in STAR).

Results from HEAP, although not significant at the 5% level, suggested an increased risk of sensitisation to egg in the intervention group. Similarities in results from STEP and HEAP (no associations found) may be related to the longer duration of the intervention in these two trials.

A major difference between the trials which may explain the different outcomes is the timing of egg introduction to the control groups with respect to the commonly measured outcome time of 12 months. BEAT and STAR controls were encouraged to consume egg from 8 months, STEP controls from 10 months, and HEAP and PETIT controls from 12 months. This difference may have influenced the timing of IgE response to egg introduction in the controls which may in turn have changed the magnitude and direction of association when compared to the intervention group. For example, if children in the HEAP trial had not been exposed to egg prior to egg allergy testing, then they may appear less “sensitised” compared to exposed populations.

In summary, the methodological differences which may have resulted in different findings include: the trial population, the sample size, the start and end date of the intervention, the treatment of the control group with respect to the intervention and how the outcomes were analysed.

The main drawback of RCT’s is external validity or how generalizable the trial results are [7]. The best way to overcome questions related to external validity is to recruit a representative sample form the general population. Therefore, a random selection of a sample from the general population is the first step followed by randomisation of the enrolled participants. Based on these two factors it can be decided whether the results are truly generalizable and how the results could be incorporated into policy. Furthermore, there is evidence that the external validity determines where the trial sits truly in the evidence hierarchy [7].

Evidence from RCTs cannot be taken at face value. All evidence, regardless of study type, needs to be critically evaluated with respect to methodology even though RCT’s are considered the highest level of evidence. We suggest that the evidence presented by these RCTs is insufficient to confirm that early egg consumption reduces future egg sensitisation and allergy. Larger trials based on the general population accounting for baseline disparities among the trial arms should be our future focus.

References

- Natsume O, Kabashima S, Nakazato J, Yamamoto Hanada K, Narita M, et al. (2017) Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (PETIT): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet 389(10066): 276-286.

- Bellach J, Schwarz V, Ahrens B, Trendelenburg V, Aksünger Ö, et al. (2017) Randomized placebo-controlled trial of hen’s egg consumption for primary prevention in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 139(5): 1591- 1599.

- Wei-Liang Tan J, Valerio C, Barnes EH, Turner PJ, Van Asperen PA, et al. (2017) A randomized trial of egg introduction from 4 months of age in infants at risk for egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 139(5): 1621-628.

- Palmer DJ, Sullivan TR, Gold MS, Prescott SL, Makrides M (2017) Randomized controlled trial of early regular egg intake to prevent egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 139(5): 1600-1607.

- Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, Bunmi Raji, Salma Ayis, et al. (2016) Randomized Trial of Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Breast-Fed Infants. New England Journal of Medicine 374: 1733-1743.

- Palmer DJ, Metcalfe J, Makrides M, Gold MS, Quinn P, et al. (2013) Early regular egg exposure in infants with eczema: A randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132(2): 387-392.

- Stuart EA, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ (2015) Assessing the Generalizability of Randomized Trial Results to Target Populations. Prevention science : the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research 16(3): 475-485.

Mini Review

Mini Review