Abstract

Purpose: Epidemiologic evidence concerning the effects of environmental factors and genetic susceptibility on the severity of asthma has been investigated. This study aimed to identify and evaluate risk factors according to asthma severity based on symptoms in South Korea children aged 6-7 years and 13-14 years.

Methods: The parents or guardians of 7,724 children who met the study criteria, i.e., had undergone a skin prick test (SPT) and had available International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood data were asked to participate. Of these 7,724 children, we selected all children who had ever had symptoms and had been diagnosed with asthma in their lifetimes (n=421). Then, we determined symptom severity using a scripted set of questions regarding the frequency of daytime and nighttime symptoms and any limitation in activities in the previous 12 months.

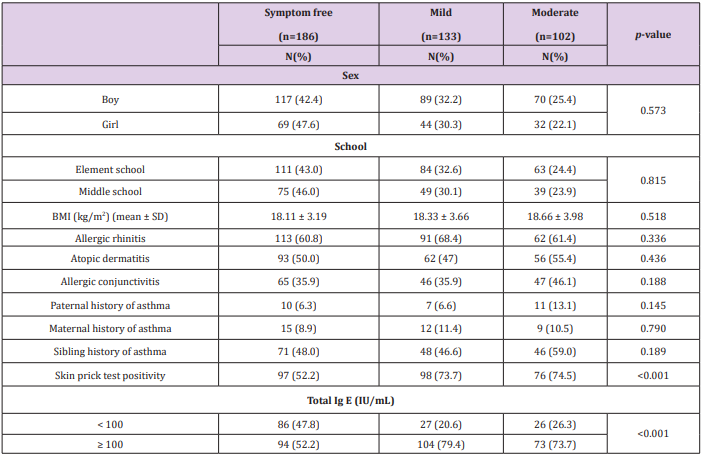

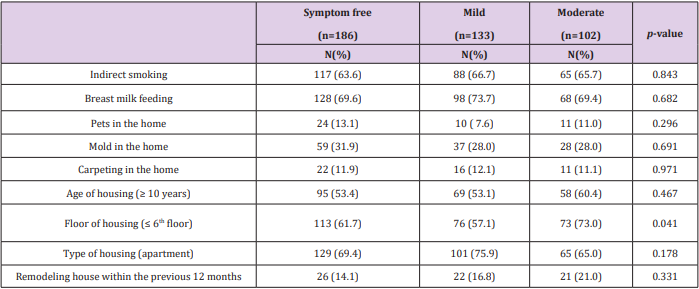

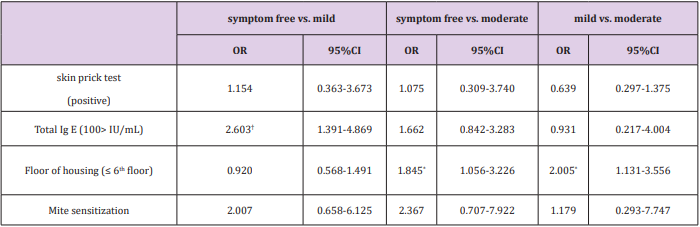

Results: Of the 7,724 children who were enrolled, 186 (2.4%) had symptom free group, 133 (1.7%), had mild symptoms, and 102 (1.3%) had moderate symptoms. The univariate analysis relating risk factors for symptom severity was significant for SPT positivity and total IgE ≥100 IU/mL (P < 0.001), living lower than the 6th floor (P = 0.041), and sensitization rate to the 3 mite allergens (P < 0.001). Multinomial logistic regression analysis for risk factors showed that total IgE ≥100 IU/mL was only risk factor for mild group compared with symptom free group (OR 2.603; CI:1.391-4.869) and living lower than the 6th floor was an independent risk factor for moderate group compared with symptom-free and mild group (OR, 1.845; CI:1.056-3.226 and OR, 2.005; CI:1.131-3.556, respectively).

Conclusion: Our data show what living environmental factor is the most important risk factor for symptom severity in children with asthma.

Keywords: Asthma; Environmental Factors; Children; Symptom Severity

Introduction

It is estimated that approximately 300 million people of all ages worldwide are asthmatic, with significant variations in prevalence between different countries and regions [1-3]. Asthma that persists throughout childhood and into adulthood is the greatest burden; therefore, it is the primary target for prevention programs [4]. Because the severity of asthma fluctuates over time and is influenced by various triggers, reducing exposure to modifiable risk factors is essential [5]. The majority of studies conducted on 6- to 14-year-old children have identified the following risk factors for asthma: parental history of asthma, history of eczema, allergic rhinitis, allergic sensitization to aeroallergens, increased serum IgE concentrations, living in a residential area, and wheezing related to high body mass index; the effects of some factors vary between studies [2,4,6-9]. Previous studies focused only on genetic or environmental factors [10,11]. Usually, asthma severity is determined according to the guidelines for classifying asthma severity, which divides patients into intermittent or persistent asthma groups and into mild, moderate, or severe groups [12]. However, the same criteria are difficult to apply to young children and adolescents who have not undergone pulmonary function tests in actual clinical practice. Generally, people are concerned only about the patterns of symptoms, without classifying asthma severity based on tests. Therefore, we evaluated risk factors according to asthma severity based on symptoms for general population can easily recognize symptom state and risk factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Potential participants were identified by a review of data collected by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Using a stratified two-stage cluster sampling design, the ISAAC has surveyed the parents or guardians of a representative sample of children aged 6-7 years and 13-14 years attending 45 elementary schools and 40 middle schools in South Korea between October and November 2010. The parents or guardians of 8,696 students provided informed consent for their children’s participation, yielding a response rate of 92.1-93.8%. Of these 8,696 children, 7,724 met the study criteria, which included having had a skin prick test (SPT) and the availability of ISAAC because their parents or guardians completed the standard ISAAC questionnaire on their behalf. Of these 7,724 children, we selected all children who had ever had symptoms and had been diagnosed with asthma in their lifetimes (n=421). A diagnosis of asthma was identified when the parent recorded on the survey that asthma had been diagnosed by a physician within the child’s lifetime.

Symptom severity was determined according to the number of asthma attacks and effect on social or academic life. The symptom-free group (n=186) was defined as those children who had not experienced wheezing for 12 months; the mild group (n=133) was defined as those who experienced wheezing ≤12 times a year and had an absence of nocturnal symptoms and any limitation in activities (e.g., difficulty speaking due to wheezing or school absenteeism); the moderate group (n=102) was defined as those who experienced wheezing ≥13 times a year, had nocturnal symptoms ≥1 time a week, and suffered from any sorts of limitations in activities. Written informed consent from a parent or guardian was obtained at the time of enrollment.

Measures

The parents or guardians of the participating children were asked to complete a validated questionnaire containing items regarding risk factors, and their children answered the ISAAC questionnaire on allergic diseases including asthma. The questionnaire included questions on basic demographic information, early and current home environmental exposure to asthma triggers, and diseases or symptoms experienced by the children and their family members. The definition of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke included exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke in the home, and the definition of exposure to home dampness and mold included exposure to visible mold and/or wet or damp spots on indoor surfaces in the home. Residential floors were categorized as the 6th floor or lower vs. higher than the 7th floor, and determination of the age of a housing structure was based on the year of its construction. Recent exposure to remodeling was scored based on the response to the question, “Has any remodeling been performed over the last 12 months in the dwelling in which your child lives?”

Recent exposure to newly-built furniture was scored based on the response to the question, “Have you placed newly-built furniture in the area in which your child usually resides over the last 12 months?” Habitation in a new or remodeled house before 1 year of age was based on the response to the question, “Did you move to a new or remodeled house within the first year after your child’s birth?” All subjects underwent a standard SPT panel to detect exposure to the following 18 inhalant allergens: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p), Dermatophagoides farinae (Der f), Tyrophagus putrescentiae (Tyr p), cockroaches, cats, dogs, alder, birch trees, oak trees, Japanese cedar (Lofarma, Milan, Italy), orchard grass, Bermuda grass, Timothy grass, mugwort, ragweed, Japanese hop, Alternaria alternata, and Aspergillus fumigatus. Histamine was used as a positive control and normal saline was used as a negative control. A mean wheal diameter ≥3 mm greater than that of the negative control was considered a positive reaction. Unless otherwise stated, the allergens were provided by Allergopharma (Reinbek, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Chi-squared tests were used to compare the prevalence of risk factors between the 3 groups. A multinomial logistic regression model assessed the relative effect of each risk factor on the presence of symptom severity (symptom free, mild, and moderate), giving the 95% confidence interval (CI) at a 5% level of significance.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at Dankook University Cheonan (IRB approval number: DKUH IRB 2010-09-0260). Written informed consent was confirmed by the IRB and obtained from all parents prior to participation in this study.

Results

Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors on the Severity of Asthma

Of the 7,724 children who were enrolled, 186 (2.4%) made up the symptom-free group, 133 (1.7%) made up the mild group, and 102 (1.3%) made up the moderate group. The risk factors significantly affecting symptom severity were SPT positivity and total IgE ≥100IU/mL (P< 0.001) (Table 1). The prevalence of SPT positivity (74.5%) was higher in the moderate group than in the symptom-free (52.2%) and mild (73.7%) groups.

Environmental Factors are Associated with Symptom Severity

Children who lived lower than the 6th floor were more likely to have moderate asthma (73%) than to be symptom-free (61.7%) or have mild asthma (57.1%) (P = 0.041). However, there were no statistical differences in other environmental risk factors, including exposure to secondhand smoke, pets, mold, age of housing, and remodeling (Table 2).

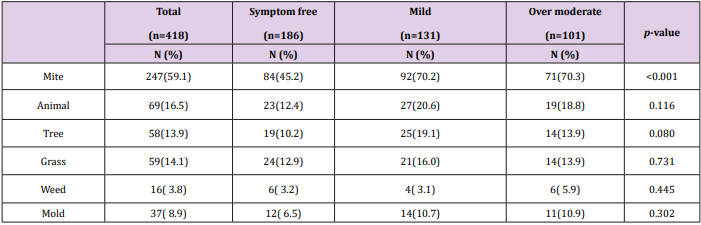

The Relationship of Inhalant Allergen Sensitization Rate to Symptom Severity

Sensitization rate to the 3 mite allergens (Der p, Der f, and Tyr p) was much higher in those in the moderate group compared to those in the symptom-free and mild groups, and this difference was statistically significant (70.3%, 45.2% and 70.2%, respectively; P < 0.001) (Table 3). Sensitization to pollen and mold was also higher in those in the moderate group than in those who were in the symptom-free and mild groups, but this was not statistically significant.

Table 3: Relation of inhalant allergen sensitization rate to asthma symptom severity.

Note:Mite antigens, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p), Dermatophagoides farinae (Der f), Tyrophagus putrescentiae (Tyr p); Animal antigens, cockroaches, cats, dogs; Tree antigens, alder, birch trees, oak trees, Japanese cedar (Lofarma, Milan, Italy); Grass antigens, orchard grass, Bermuda grass, Timothy grass; Weed antigens, Mugwort, Ragweed, Japanese hop; Mold antigens, Alternaria alternate and Aspergillus fumigatus.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis for Risk Factors Associated with Symptom Severity

Total IgE 100 IU/mL was the only risk factor associated with the mild group compared with the symptom-free group (OR, 2.603; 95% CI:1.391-4.869) (Table 4). Living lower than the 6th floor was an independent risk factor for the moderate group compared with the symptom-free and mild groups (OR, 1.845; 95% CI:1.056-3.226; and OR, 2.005; 95% CI:1.131-3.556) (Table 4).

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis assessing the risk factors associated with asthma symptom severity.

Note: *p < 0.05; †p < 0.01

Discussion

This was a population-based study on risk factors for asthma in Korea that included 7,724 children from 85 randomly selected schools. Asthma severity is measured by the degree of impairment in physical, social, and academic life. However, it is difficult to assess asthma severity in children because young children can’t perform lung function tests. Therefore, physicians usually classify severity according to clinical symptoms. Thus, we classified severity into three groups, symptom-free, mild, and moderate, with clinical symptoms from reference guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma [12]. Multiple risk factors impact asthma severity; therefore, it is important that we identify the most important risk factors and maintain a well-controlled environment that will reduce the severity of asthma [10]. This study is significant in that it analyzed risk factors for asthma in a representative population of Korean children; it used a well-designed, stratified two-stage cluster sampling method and classified severity using clinical symptoms without pulmonary function tests.

In the present study, more extreme allergen sensitization was a risk factor for symptom severity. SPT positivity was higher in the moderate group than in the symptom-free and mild groups, and total IgE ≥100 IU/mL was more prevalent in the mild and moderate groups than in the symptom-free group. Others studies suggested that total IgE concentration and combined sensitivity to cats, dogs, dust mites, and cockroaches contributed to disease severity [10,13]. In addition, there are studies showing that asthma severity increases with increasing sensitization to dust mites and that reduced pulmonary function is correlated with dust mitespecific IgE titer [14,15]. We identified an association between sensitivity to dust mites and symptom severity in our univariate analysis. However, genetic predisposition and sibling and parental history were not associated with symptom severity in the present study. Environmental factors such as air pollution and smoking are well-known risk factors for asthma severity [10,11,16]. Living below the 6th floor was determined to be a risk factor for symptom severity in our study. However, there were no statistical differences in other environmental risk factors, including exposure to secondhand smoke, pets, mold, age of housing, and remodeling. Multinomial logistic regression analysis for risk factors associated with symptom severity showed that living lower than the 6th floor was an independent risk factor for the moderate group compared with the symptom-free and mild groups.

These results are very interesting because well-known risk factors including secondhand smoke, mold, and pets were not associated with symptom severity. We inferred that natural ventilation in high-rise apartment buildings is greater than in lowrise buildings. Low ventilation rates increase the effects of indoor air pollutants [18]. Deger, reported that living on the basement level was the strongest risk factor for poor asthma control [8]. At lower levels within apartment buildings, the slower frequency of air turnover may result in higher levels of pollutants produced indoors, as well as increased humidity levels, favoring an indoor climate that may be associated with adverse health effects and recurrent wheezing [18,19]. Others studies also concluded that the prevalence of asthma and skin reactions to dust mites and aeroallergens were much lower in those living at high altitude than those living at sea level [20-23]. Therefore, superior ventilation at higher levels may act to decrease aeroallergen concentrations and sensitization. In the present study, sensitization to aeroallergen was also higher in those living lower than the 6th floor than those living higher than the 7th floor (60.6% vs 39.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant. We suggest that the reason for the absence of statistical significance is an inadequate sample size.

Our results suggest that living lower than the 6th floor is a significant risk factor for increased asthma symptom severity because of a difference in sensitization to dust mites and other aeroallergens. We showed that living environment is the most important risk factor for moderately severe asthma in children. However, the present data do not clarify which underlying conditions or exposures might fully explain the results. Therefore, further investigation is needed, including measurements of homes infested with dust mites and aeroallergens or humidity levels by building height. This study has several limitations. First, the asthma severity classification was based solely on self-reported information and did not include lung function test results or medication history. Therefore, we classified severity based on symptoms. Second, as the parents and guardians retrospectively completed the items on the ISAAC survey, their responses may have been affected by recall bias. In particular, the extent of their child’s environmental exposure to such factors as dampness and mold, chemicals in newly-built housing during infancy, and secondhand tobacco smoke could have been affected. However, this population-based study included a representative sample of the general population in Korea, which allowed for multivariate and subgroup analyses, including analysis of a wide range of asthma-related risk factors. This study suggests that living on lower floors is an important risk factor for children with moderate asthma. Furthermore, the association between this environmental factor and asthma severity should be studied with more subjective classification of severity and tests which measure the concentration of aeroallergens.

References

- Cooper P, Rodrigues L, Cruz A, Barreto M (2009) Asthma in Latin America: a public heath challenge and research opportunity. Allergy 64(1): 5-17.

- Suh M, Kim H, Choi DP, Kim KW (2011) Association between body mass index and asthma symptoms among Korean children: a nation-wide study. Journal of Korean Medical Science 26(12): 1541-1547.

- Ahn K, Kim J, Kwon H, Chae Y (2011) The prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in Korean children: Nationwide cross-sectional survey using complex sampling design. Journal of Korean Medical Association 54(7): 769-778.

- Sly PD, Boner AL, Björksten B, Bush A (2008) Early identification of atopy in the prediction of persistent asthma in children. The Lancet 372(9643): 1100-1106.

- Calhoun WJ, Sutton LB, Emmett A, Dorinsky PM (2003) Asthma variability in patients previously treated with beta2-agonists alone. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 112(6): 1088-1094.

- Ahni YO (2001) Prevalences of symptoms of asthma and other allergic diseases in Korean children: a nationwide questionnaire survey. Journal of Korean Medical Science 16(2): 155-164.

- Hong S, Lee M, Sohn M, Shim J (2004) Self‐reported prevalence and risk factors of asthma among Korean adolescents: 5-year follow-up study, 1995-2000. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 34(10): 1556-1562.

- Deger L, Plante C, Goudreau S, Smargiassi A (2010) Home environmental factors associated with poor asthma control in Montreal children: a population-based study. The Journal of Asthma 47(5): 513-520.

- Panettieri Jr RA, Covar R, Grant E, Hillyer EV (2008) Natural history of asthma: Persistence versus progression—does the beginning predict the end? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 121(3): 607-613.

- Awasthi S, Gupta S, Maurya N, Tripathi P (2012) Environmental risk factors for persistent asthma in Lucknow. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 79(10): 1311-1317.

- Higgins PS, Wakefield D, Cloutier MM (2005) Risk factors for asthma and asthma severity in nonurban children in Connecticut. CHEST 128(6): 3846-3853.

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (2007) Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. ournal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 120(5 Suppl): S94-138.

- Sarpong SB, Karrison T (1998) Skin test reactivity to indoor allergens as a marker of asthma severity in children with asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 80(4): 303-308.

- Leung TF, Lam CW, Chan IH, Li AM (2002) Inhalant allergens as risk factors for the development and severity of mild-to-moderate asthma in Hong Kong Chinese children. The Journal of Asthma 39(4): 323-330.

- Choi SY, Sohn MH, Yum HY, Kwon BC (2005) Correlation between inhalant allergen-specific IgE and pulmonary function in children with asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology 39(2): 150-155.

- Yuenyongviwat A, Koonrangsesomboon D, Sangsupawanich P (2013) Recent 5-year trends of asthma severity and allergen sensitization among children in southern Thailand. Asian Pacific Journal of Allergy and Immunology 31(3): 242-246.

- Lin S, Gomez MI, Hwang SA, Munsie JP (2008) Self-reported home environmental risk factors for childhood asthma: a cross-sectional study of children in Buffalo, New York. The Journal of Asthma 45(4): 325-332.

- Oie L, Nafstad P, Botten G, Magnus P (1999) Ventilation in homes and bronchial obstruction in young children. Epidemiology 10(3): 294-299.

- Lindfors A, Wickman M, Hedlin G, Pershagen G (1995) Indoor environmental risk factors in young asthmatics: a case-control study. Archives of Disease in Childhood 73(5): 408-412.

- Emenius G, Svartengren M, Korsgaard J, Nordvall L (2004) Building characteristics, indoor air quality and recurrent wheezing in very young children (BAMSE). Indoor Air 14(1): 34-42.

- Charpin D, Kleisbauer JP, Lanteaume A, Razzouk H (1988) Asthma and allergy to house-dust mites in populations living in high altitudes. Chest 93(4): 758-761.

- Charpin D, Birnbaum J, Haddi E, Genard G (1991) Altitude and allergy to house-dust mites. A paradigm of the influence of environmental exposure on allergic sensitization. The American Review of Respiratory Disease 143(5pt 1): 983-936.

- Ozkaya E, Sogut A, Kucukkoc M, Eres M (2015) Sensitization pattern of inhalant allergens in children with asthma who are living different altitudes in Turkey. International journal of biometeorology 59(11): 1685-1690.

Research Article

Research Article