Introduction

Inflammatory Breast Cancer (IBC) is the most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer [1-3]. IBC represents ~2-4% of breast cancers in the USA [4] and accounts for ~7-10% of all breast cancer deaths [5]. The 5-year survival rate for IBC is less than 50%, significantly less than patients with non-IBC breast cancer (85%) [6,7]. Further, IBC affects young, African-American and AmericanIndian women at a higher rate than in other groups [8-10]. The diagnosis criteria used for IBC patients are based on clinical characteristics. In IBC, the tumor cells are typically distributed diffusely in the breast instead of forming a solid tumor. These cells cluster to form emboli that block the lymphatic vessels in the skin covering the breast, causing a characteristic red, warm and thickened appearance of the breast termed peau d’orange. Hence, IBC tumors are not easily detected by mammogram with detection typically after the cancer has spread [1,3].

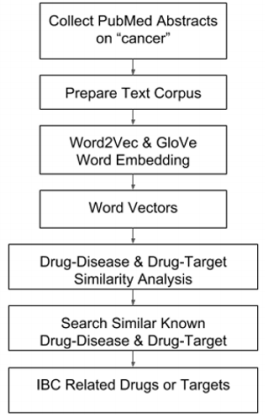

Despite polychemotherapy regimens, women with IBC continue to have worse survival outcomes than non-IBC breast cancer patients [11,12]. Most IBC tumors are negative for Estrogen Receptor (ER) and nearly 40% of IBC patients exhibit the triple negative phenotype (ER-/PR-/HER2-) rendering hormonal and HER2-targeted therapies ineffective. The major clinical challenges facing patients with IBC are the development of resistance to initially effective therapeutics, and metastatic spread of the disease [7,13-15]. To date, no therapeutics have been developed that target IBC specifically. Thus, novel research is required to identify effective therapies for treating IBC, among which repurposing existing drugs via word embedding analysis constitutes an attractive strategy. Word embedding technologies have emerged from the text mining field in recent years as a novel drug repurposing strategy in various therapeutic areas. For example, Ngo et al. [16] employed Word2Vec [17] to analyze a corpus of biomedical text that consisted of a subset of the PubMed abstracts filtered by the keyword “cancer”. From over 3 million abstracts, 14 million sentences were extracted. Using the Word2Vec embedding technology, over 1.7 M words were embedded into word vectors, including those for 2303 drugs and 3069 diseases. Combining the word vectors and known drug-disease relations from drugbank [17], machine learning technology was employed to build models to uncover new drug-disease relations. Their trained model achieved > 87% accuracy in the prediction of known drug-disease relations and succeeded in discovering novel drug-disease relations that were reported in the literature. Here, we report a perspective that describes a similar but unique approach that combines two text mining technologies to derive word vectors for drugs, cancers and their potential targets. Existing relations among drugs, diseases and targets will be extracted from Chem2Bio2RDF, a systems chemical biology database [18]; newer relations will be directly extracted from current version of Drug Bank [17]. Unknown relations that can potentially link various drugs to IBC will be predicted based on simple similarity principle.

Literature-Wide Association Study (LWAS) For IBC Drug Repurposing

Since the proposed approach conducts PubMed literature wide survey to identify associations between biological concepts, we term this approach LWAS (Literature-Wide Association Study). The overall workflow for LWAS-IBC drug repurposing is shown in Figure 1. The individual components are detailed as follows. Collecting and Preprocessing of PubMed Abstracts A search of the PubMed database with “cancer” as the search term revealed over 3 million abstracts. This body of literature will be periodically updated and further processed to construct sentences, which will be subject to the word embedding analyses by two complementary technologies below to derive word vectors for all the terms (vocabulary) in it. Performing Word Embedding Analyses First, the Word2Vec technology [17] originally developed by Google for semantic relationship analysis will be used to establish relationships among biological terms.

Figure 1: Frequency of different immune cell populations of Mr M. R’s PBMCs during the clinical study.

All these graph results were obtained from flow cytometry assay.

a) Frequency of CD3+ cells (black) and CD3- cells (white) in total PBMCs.

b) Frequency of different cell types in Mr M. R’s PBMCs: CD4 +, CD8 +, CD11c +, CD14+, CD19+ and CD335+.

c) Frequency of nTregs (in black) and iTregs (CD4+CD18+CD49b+ in white and CD4+Lag3+CD49b+ in grey) within CD4+ T lymphocytes. D) Frequency of dendritic cells (in black) and B lymphocytes (in white) in CD3- sub-population.

The Gensim implementation of this algorithm is used in this analysis. According to this technology, each biological term will be converted and represented by a high dimensional vector (e.g. 200 dimension), and the similarity (relatedness) among different terms will be captured by the cosine similarity for any two terms. This analysis will generate potential relatedness between IBC and other biological concepts, such as gene/protein names, clinical parameters, diseases and drugs. This “relatedness” information will be used to generate new hypotheses for drug repurposing. Secondly, the word association tool GloVe [19], originally developed by the Stanford natural language processing group, will be employed to analyze the same textual corpus. Like how Word2Vec works, GloVe will generate word associations based on the frequency of co-occurrence between all pairs of interested biological concepts. The co-occurrence information will then be used to derive word embedding vectors.

Both techniques are based on the intuitive notion that biomedical terms (drug names, disease names and target names) co-occur frequently in the same contextual environment (in proximity in sentences) often imply their inter-relatedness and are combined with neural network learning to discover highly related drugs and targets.

Similarity Analysis of Drug Vectors, Disease Vectors and Target Vectors

Our approach will be to first generate critical terms that will allow us to explore the above embedding results related to IBC. For example, a clinical hallmark of IBC is dermal lymphatic invasion by clusters of tumor cells which migrate collectively, termed tumor emboli. These emboli block the lymphatic vessels in the skin covering the breast, causing a characteristic red, warm and thickened appearance termed peau d’orange. These terms (e.g. tumor emboli, dermal lymphatic invasion, peau d’orange) can be explored by similarity search in the embedded (both Word2Vec and GloVe) space to identify related concepts such as drugs, targets and other diseases, which in turn provide additional hypotheses for mechanism studies and drug repurposing. Other molecular markers/genes, clinical features and pathological features/terms directly related to IBC [12,20-26] can be explored as well by similarity analysis based on the embedded word vectors.

Database Search for Known Drug-Disease and Drugtarget Relations

Systems biology database such as Chem2Bio2RDF [18] has integrated data from different sources. Web based resources such as Drug Bank [17] also provide useful information for drug repurposing efforts. For example, we have identified > 10,000 known drug-target pairs from Chem2Bio2RDF, and over 1000 drug-disease pairs from combined Drug Bank and KEGG. Similarity analysis from the previous step can reveal which drugs are like each other based on drug vectors and which diseases may be similar based on disease vectors. We can search the known drug-target pairs and drug-disease pairs to identify which diseases and drugs may be useful for IBC. This combined word embedding analysis and database search can afford interesting hypotheses for follow-up experiments. For example, if we find that IBC is related to “ovarian cancer”, then drugs known for “ovarian cancer” can be tested for their potential use in treating IBC, which serves as a new starting point for drug discovery programs [27-39].

Concluding Remarks

Currently there is a lack of therapeutics for IBC. We described a perspective that a text mining approach may help discover novel relations that can establish potential links between IBC and other diseases, targets and existing drugs. The outcome of the proposed analyses includes [1] potential targets for IBC mechanism research and [2] a list of drugs that can be tested for their efficacy in in vitro and in vivo IBC models [40-44]. To our best knowledge, this work would be the first to employ Natural Language Processing (NLP) technologies to generate word embedding models that allow us to mine for IBC-specific topics. The software used in this proposed study has been previously published, verified and is broadly applicable; thus, it also provides a generic protocol that can be applied to other cancers (other diseases) as well.

With the new experimental data, we can then validate and refine the word embedding models. In addition, various novel machine learning techniques in scikit-learn will be employed to analyze the new data. We will also perform drug similarity analysis based on chemical descriptors (rather than embeddings), which further expands the approach to enable the discovery of New Chemical Entities (NCE) beyond just drug repurposing for IBC. This combined text mining and cheminformatics approach should afford a greater opportunity for IBC therapeutic discovery

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by NIH awards P20CA202924 and U54CA137844, and Komen Graduate Training in Disparities Research award GTDR16377604 (KPW). It was also supported in part by the subaward from UNC-CH to WZ (via NIH U01CA207160).

References

- NCI (2015) Inflammatory Breast Cancer. National Cancer Institute Web site.

- NW Houchens, SD Merajver (2008) Molecular determinants of the inflammatory breast cancer phenotype. Oncology 22(14): 1556-1561.

- M Cristofanilli, AU Buzdar, GN Hortobagyi (2003) Update on the management of inflammatory breast cancer. Oncologist 8 (2) 141-148.

- Chang S, Parker SL, Pham T, Buzdar AU, Hursting SD (1998) Inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program of the National Cancer Institute, 1975-1992. Cancer 82(12): 2366-2372.

- Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine PH (2005) Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program at the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(13): 966-975.

- Cristofanilli M, Valero V, Buzdar AU, Kau SW, Broglio KR, et al. (2007) Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) and patterns of recurrence: understanding the biology of a unique disease. Cancer 110 (7): 1436- 1444.

- WF Anderson, C Schairer, BE Chen, KW Hance, PH Levine (2006) Epidemiology of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) Breast disease 22: 9-23.

- WA Woodward, M Cristofanilli (2009) Inflammatory breast cancer. Semin Radiation Oncology 19 (4) 256-265.

- Schlichting JA, Soliman AS, Schairer C, Banerjee M, Rozek LS, et al. (2011) Association of Inflammatory and Non-Inflammatory Breast Cancer with Socioeconomic Characteristics in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Database, 2000-2007. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 21(1): 155-165.

- S Dawood, K Broglio, AU Buzdar, GN Hortobagyi, SH Giordano (2010) Prognosis of women with metastatic breast cancer by HER2 status and trastuzumab treatment: an institutional-based review. J Clin Oncol 28(1): 92-98.

- WA Woodward (2015) Inflammatory breast cancer: unique biological and therapeutic considerations. The Lancet Oncology 16(15): e568-e576.

- Charafe Jauffret E, Tarpin C, Bardou VJ, Bertucci F, Ginestier C, et al. (2004) Immunophenotypic analysis of inflammatory breast cancers: identification of an ‘inflammatory signature. J Pathol 202(3): 265-273.

- Lee WY1, Su WC, Lin PW, Guo HR, Chang TW, et al. (2004) Expression of S100A4 and Met: potential predictors for metastasis and survival in early-stage breast cancer. Oncology 66(6) 429-438.

- K Crane (2011) Elucidating an Uncommon Disease: Inflammatory Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(18): 1358-1360.

- DL Ngo, N Yamamoto, VA Tran, NG Nguyen, D Phan, FR Lumbanraja, et al. (2016) Application of Word Embedding to Drug Repositioning J BiomedSci Engineering 09: 7-16.

- Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, et al. (2018) DrugBank 50: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 46(D1): D1074-D1082.

- Chen B, Dong X, Jiao D, Wang H, Zhu Q, et al. (2010) Wild DJ Chem2Bio2RDF: a semantic framework for linking and data mining chemogenomic and systems chemical biology data BMC Bioinformatics 11: 255

- HB Adkins, C Bianco, SG Schiffer, P Rayhorn, M Zafari, et al. (2003) Antibody blockade of the Cripto CFC domain suppresses tumor cell growth in vivo. J Clin Invest 112(4): 575-587.

- R Costa, CA Santa Maria, G Rossi, BA Carneiro, YK Chae, et al. (2017) Developmental therapeutics for inflammatory breast cancer: Biology and translational directions. Oncotarget 8(7): 12417-12432.

- SV Fernandez, FM Robertson, J Pei, L Aburto Chumpitaz, Z Mu, et al. (2013) Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC): clues for targeted therapies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140(1): 23-33.

- MK Jolly, M Boareto, BG Debeb, N Aceto, MC Farach Carson, et al. (2017) Inflammatory breast cancer: a model for investigating cluster-based dissemination. NPJ breast cancer 3: 21.

- D Van Uden, H van Laarhoven, A Westenberg, J De Wilt, C Blanken Peeters, et al. (2015) Inflammatory breast cancer: an overview, Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 93(2): 116-126.

- RJ Morrow, N Etemadi, B Yeo, M Ernst (2017) Challenging a misnomer? The role of inflammatory pathways in inflammatory breast cancer. Mediators of inflammation.

- F Bertucci, N Ueno, P Finetti, P Vermeulen, A Lucci (2013) Gene expression profiles of inflammatory breast cancer: correlation with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and metastasis-free survival. Annals of oncology 25(2): 358-365.

- SJ Van Laere, NT Ueno, P Finetti, P Vermeulen, A Lucci, et al. (2013) Uncovering the molecular secrets of inflammatory breast cancer biology: an integrated analysis of three distinct affymetrix gene expression datasets. Clinical cancer research 19(17): 4685-4696.

- J Arora, SJ Sauer, M Tarpley, P Vermeulen, C Rypens, et al. (2017) Inflammatory breast cancer tumor emboli express high levels of anti-apoptotic proteins: use of a quantitative high content and highthroughput 3D IBC spheroid assay to identify targeting strategies. Oncotarget 8(16): 25848-25863.

- . JZ Sexton, PV Danshina, DR Lamson, M Hughes, AJ House, et al. (2011) Development and Implementation of a High Throughput Screen for the Human Sperm-Specific Isoform of Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDHS). Current Chemical Genomics 5: 30-41.

- JZ Sexton, Q He, LJ Forsberg, JE Brenman (2010) High content screening for non-classical peroxisome proliferators. Int J High Throughput Screen 10(1): 127-140.

- JZ Sexton, TJ Wigle, Q He, MA Hughes, GR Smith, et al. (2010) Novel inhibitors of E coli RecA ATPase activity. Curr Chem Genomics 4: 34-42.

- T Mikolov, K Chen, G Corrado, J Dean (2013) Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv: 13013781.

- J Pennington, R Socher, C Manning (2014) Glove: Global vectors for word representation. Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP) pp. 1532-1543.

- Saloman DS, Bianco C, Ebert AD, Khan NI, De Santis M, et al. (2000) The EGF-CFC family: novel epidermal growth factor-related proteins in development and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 7(4): 199-226.

- Thomas ZI, Gibson W, Sexton JZ, Aird KM, Ingram SM, et al. (2011) Targeting GLI1 expression in human inflammatory breast cancer cells enhances apoptosis and attenuates migration, Br J Cancer, 104(10): 1575-1586.

- W Janzen, P Bernasconi, L Cheatham, P Mansky, I Popa Burke, et al. (2004) Optimizing the chemical genomics process. Chem Genomics p. 59-100.

- J Norris, K Williams, W Janzen, C Hodge, L Blackwell, et al. (2005) Selectivity of SB203580, SB202190 and other commonly used p38 inhibitors: profiling against a multi-enzyme panel. LETTERS IN DRUG DESIGN AND DISCOVERY 2(7): 451-455.

- K Williams, J Scott, Enzyme assay design for high-throughput screening, Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ), 565 (2009) 107-126.

- KP Williams (2006) A Chemogenomic Approach to Kinase Drug Discovery. EuroConference on Protein KinasesPasteur Institute France.

- KP Williams (2006) Rational Approaches to Targeted Drug Design, 1st Targeted Therapies Workshop of the Duke Comprehensive Cancer CenterPinehurst, NC.

- HO Oladapo, M Tarpley, SJ Sauer, KA Addo, SM Ingram, et al. (2017) Pharmacological targeting of GLI1 inhibits proliferation, tumor emboli formation and in vivo tumor growth of inflammatory breast cancer cells. Cancer letters 411: 136-149.

- SJ Sauer, M Tarpley, I Shah, AV Save, HK Lyerly, et al. (2017) Bisphenol A activates EGFR and ERK promoting proliferation, tumor spheroid formation and resistance to EGFR pathway inhibition in estrogen receptor-negative inflammatory breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 38(3): 252-260.

- ZI Thomas, W Gibson, JZ Sexton, KM Aird, SM Ingram, et al. (2011) Targeting GLI1 expression in human inflammatory breast cancer cells enhances apoptosis and attenuates migration. British Journal of Cancer 104(1): 1575-1586.

- KP Williams, JL Allensworth, SM Ingram, GR Smith, AJ Aldrich, et al. (2013) Quantitative high-throughput efficacy profiling of approved oncology drugs in inflammatory breast cancer models of acquired drug resistance and re-sensitization. Cancer Lett 337(1): 77-89.

- MS Dixon, L Chdid, D Lamson, M Tarpley, JM Fleming, et al. (2018) Determining the role of novel GLI1 splice variants in breast cancer, AACR, 2018.

- R Costa, CA Santa Maria, G Rossi, BA Carneiro, YK Chae, et al. (2017) Developmental therapeutics for inflammatory breast cancer: Biology and translational directions. Oncotarget 8(7): 12417-12432.

Mini-Review

Mini-Review