Abstract

Introduction: As social media is commonly used among adolescents in recent years, new form of bullying, cyberbullying has been reported increasing. This study examined the association between being cyberbullied and emotional-behavioral problems using self-reported data.

Methods: A total of 4372 participants, aged from 13 to 18 years (mean age 15.20 ± 1.66 years) completed self-report web-based questionnaires through the Thai Youth Risk Behavior Survey. The Youth Self-Report was obtained from participants to assess emotional and behavioral problems.

Results: Seven hundred and fifty-nine participants (17.4%) have reported being cyberbullied, whereas 958 participants (21.9%) were school bullied. Co-occurring being cyberbullied and school bullied were found in 8.7%. Participants who were reported being cyberbullied or school bullied or both had significantly greater behavioral scores than those who were not (p<0.001). The highest behavioral scores were reported by participants who were being both cyber and school bullied. Being cyberbullied and school bullied, as well as age and gender of participants were significantly associated with greater behavioral problem scores from multiple linear regression analysis. After adjusting for covariates, being cyberbullied was found to be associated with reports of depression (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 2.77, 95% confidence interval, CI 2.32-3.30), suicidal ideation (aOR 3.92, 95% CI 3.02-5.08), and suicidal attempt (aOR 3.46, 95% CI 2.54-4.71).

Conclusion: Findings suggest that victims of cyberbullying with or without school bullying may be at a high risk of poor emotional-behavioral functioning. There is a need for intervention programs helping adolescents who suffer from being cyberbullied.

Keywords: Cyberbullying; Electronic bullying; Emotional problems; Behavioral problems; Adolescents

Abbreviations: YRBS: Youth Risk Behavior Survey; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; YSR: Youth Self-Report; ORs: Odds Ratios; AORs; Adjusted Odds Ratios; CI: Confidence Intervals

Introduction

As social media is commonly used among adolescents and has influenced their social interaction in recent years. Digital social media, especially mobile technologies, enable adolescents to explore relationships and communicate with each other without adult control. Conflicts between them can be easily staged since everybody can be reached at any time. Therefore, involvement in conflicts and bullying might be dependent on how adolescents use aggression online, a phenomenon known as cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is described as an aggressive, intentional act or behavior that is performed by an individual or a group, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend himself/herself [1-4]. It can occur through e-mails, Facebook, Twitter, text messaging, or other social networks. The number of adolescents who experience cyberbullying varies, ranging from 6.5% to 34.5% [5,6], depending on the age group, study setting and how cyberbullying is defined. The bullying messages can spread through the Internet to many other people at school or in the community, making this type of bullying very embarrassing.

The negative effects of traditional or school bullying victimization on adolescents’ emotional and behavioral problems are well documented [7,8]. Previous studies have shown that, similar to school bullying, cyberbullying can have adverse effects on victims [3,9,10]. Victims of cyberbullying are more likely to achieve lower grades and report other academic problems as a result of the experience [11]. Being cyberbullied is associated with higher levels of psychological distress and depression and lower self-esteem [2,12,13]. A meta-analysis found that victims of cyberbullying were at higher risk of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [14] whereas another study has found that cyberbullying was associated with moderate to severe depressive symptoms, substance use, and suicide attempts [5]. Furthermore, experience of cyberbullying in adolescence may be associated with later mental health problems extending into adulthood [15]. Therefore, this study aimed to study emotional and behavioral problems specifically in cyberbullied adolescents and the associations between being cyberbullied and depression and suicidal ideas. Factors predicting behavioral problems were also assessed.

Methods

Study Population

A cross-sectional survey of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years in a city in Northern Thailand was conducted. The data were collected using a two-stage stratified cluster sampling method from secondary and vocational schools. Parents were advised through school teachers that their child’s school had been invited to take part and that their child would decide whether or not to participate. Participants gave consent before completing webbased questionnaires which was responded to anonymously. Details of survey and participants are described elsewhere [16]. The Research Ethics Committee of Chiang Mai University approved the study.

Measurement

Information regarding health risk behaviors was obtained though the Thai Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Thai-YRBS) which was modified from the Youth Risk behavior Survey (YRBS) 2015 [17] developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The YRBS is a school-based survey, which monitors major health risk-taking behaviors. Being cyberbullied was identified by the following question “During the past 12 months, have you ever been electronically bullied?” (Count being bullied through e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging, websites, or texting.) The answer “yes” to the question is considered cyberbullied experience. Being school bullied was identified by the following question “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property?” The answer “yes” to the question is considered school bullied experience. Bullying is defined as one or more students tease, threaten, spread rumors about, hit, shove, or hurt another student over and over again. It is not considered as bullying when two students of about the same power argue or fight or tease each other in a friendly way.

The participants, both with and without cyberbullied experience, were asked to complete the Youth Self-Report form (YSR). The YSR is a self-administered survey and has been used widely to assess emotional and behavioral problems that have occurred within the past 6 months and are available in many languages [18,19]. It assesses internalizing (i.e., anxiety, depression and somatic complaints) and externalizing (i.e., aggressive, noncompliant) behaviors. The scale comprises internalizing, externalizing, and total behavior problems scores. It is divided into 8 subsets including anxiety/depression, social withdrawal, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, delinquent, and aggressive behaviors. Higher scores indicate more problems.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS program, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) for Windows. The percentage, mean, and standard deviation were calculated. A Chi-square test was used for the analysis of categorical variables and a student’s t test was used for continuous variables. The odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify predictors of internalizing, externalizing, total behavioral problem scores.

Results

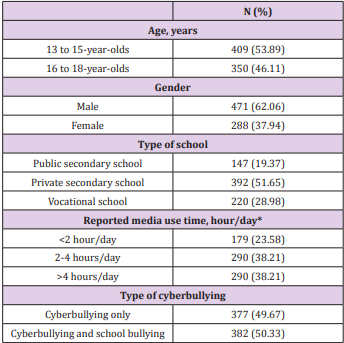

Four thousand, three hundred and seventy-two out of 5639 adolescents were randomly enrolled from the six schools which completed the web-based survey, giving a response rate of 77.53%. The average age of all participants was 15.20 ± 1.66 years. Seven hundred and fifty-nine participants reported being cyberbullied which was 17.36% of cases, whereas school bullied was found to be 21.91%. Co-occurring being cyberbullied and school bullied was found in 382 cases (8.74% of participants). Among those who reported being cyberbullied, 62% were male and 38% were female. Details of participants reporting being cyberbullied are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of participants who reported experience of being cyberbullied (n=759).

*Media use time other than school work or watching TV

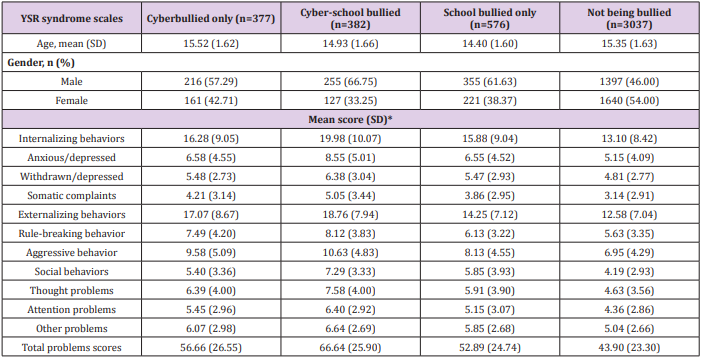

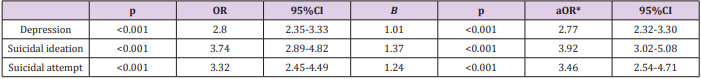

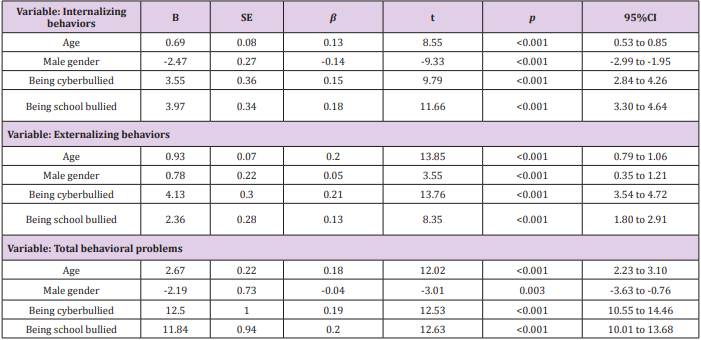

Participants who reported experience of being cyberbullied or school bullied or both had significantly higher internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral scores than those who were not being bullied. The highest behavioral scores were reported by participants with experience of being cyber-school bullied, as shown in Table 2. Being cyberbullied was found to be associated with reports of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempt when adjusting for covariates (adjusted odds ratio 2.77, 3.92 and 3.46, respectively), as shown in Table 3. From multiple linear regression analysis, being cyberbullied and school bullied, as well as age and gender of participants were significantly associated with higher internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral problem scores (Table 4).

Table 2: Youth Self-Report scales in adolescents who were and were not cyberbullied (n= 4372).

*P<0.001 between being cyberbullied only and not being bullied; cyber-school bullied and not being bullied; school bullied only and not being bullied

Table 3: Association of depression, suicidal ideation, suicidal attempt and being cyberbullied..

*Adjusted for age, gender and type of school

Table 4: Prediction of internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral problems from multiple linear regression analysis (n= 4372).

Discussion

Findings from this study have revealed that adolescents who reported being cyberbullied or school bullied or both had significantly greater internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral scores than those who were not being bullied. Subscales of behavioral scores were also higher in adolescents who reported experience of being cyberbullied. Because cyberbullying messages can quickly spread through the Internet to many other people at school or in the community, this causes emotional problems including depression, embarrassment, or anger towards perpetrators who are able to be anonymous. Cyberbullying may achieve a vastly wider audience than traditional school bullying, since it occurs in the virtual space and, additionally, it has the potential to remain permanently on a website. The hurtful messages of a cyberbully can reach the adolescents anytime he or she uses a telephone or computer. Highest behavioral scores were reported by participants with experience of cyber-school bullying. This is consistent with the study which found that people who were exposed to cyberbullying in addition to traditional bullying displayed a significantly greater severity of psychiatric symptoms [20].

Being cyberbullied was found to be associated with reports of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempt at rates of 2.77, 3.92, and 3.46 times respectively, compared with those who were not being bullied. These findings were also consistent with previous meta-analysis which found that cyberbullying was more strongly related to suicidal ideation (OR, 3.12) compared to the impact of traditional bullying (OR, 2.16; 95% CI, 2.05–2.28) [14]. Another study found that being cyberbullied was strongly associated with suicide attempts (OR, 3.22) [21]. However, there have been reports that most of the victims were not psychologically affected by the cyber-attack and did not share the event with anyone [22].

The prevalence of cyberbullying victims was 17.36%, whereas those who were school bullied were 21.91%. Among those who reported experiences of being cyberbullied, 62% were males and 38% were females and the experience was more common in private school students. These findings were different from a study which found that 9.1% of students grade 6-12 reported cyberbullying, of which 39% were male [23]. Boys were reported as being more likely to be cyber perpetrators, whereas girls were reported to be more likely to be cyber victims [24]. From a systematic review, the prevalence rates of cyberbullying victimization in US adolescents of middle and high school age ranged from 3 to 72%. This study found co-occurring cyberbullying and school bullying of 8.74% which is different from another study which reported the overlapping of cyberbullying and other types of bullying of which only 4.6% of adolescents grade 9-12 reported being only cyberbullied [25]. In another study 62% of high school students experienced cyberbullying, the main channel for the bullying being by cell phone, the highest frequency occurring in public school students [22].

The age of participants, gender and being cyberbullied as well as school bullied were associated with internalizing, externalizing, and total behavioral problems. Females were more highly associated with internalizing behavior problems whereas males were more frequently associated with externalizing behavior problems. This is consistent with the study by Kim et al. [23] who found that cyberbullying was associated more strongly with emotional problems in female adolescents and with behavioral problems in male adolescents [23]. In another study, girls and boys were found to differ not only according to their online communication use but also in their cyberbullying involvement. Girls had more intensive online social activities whereas boys had higher exposure to antisocial media content predictive of higher levels of victimization over time [26].

Limitations

In this study a representative sample of participants in the city were enrolled and the web-based anonymous questionnaires increased the level of confidentiality for the adolescents enabling accurate and useful data to be obtained. The Youth Self-Report, a verified analytical tool, was used to assess emotional and behavioral problems. However, some limitations need to be addressed. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of this study limited the ability to explore the cause and effects of the findings for example why there was a high prevalence of cyberbullying in public schools. A longer term, more in-depth study may provide more information. Secondly, the data were self-reported, and although the responses were anonymous encouraging honesty in the answer, multi information gathering strategies would provide more details concerning emotional-behavioral functioning. Thirdly, participants were from secondary and vocational schools in a city in Northern Thailand, so the findings could not be generalized. Also, adolescents 13-18 years of age who had dropped out of school were not included in this study. Lastly, details of cyberbullying were not explored such as being bullied only or being both the bully and perpetrator. Type of online aggression and how the young people deal with bullying should be examined so that intervention could be provided appropriately.

Conclusion

In summary, findings from this study have revealed that victims of cyberbullying concurrent with or without school bullying may be at high risk of poor emotional-behavioral functioning. Those experiencing both cyberbullying and school bullying may be the highest risk group. There is a need for intervention programs helping adolescents who suffer from being cyberbullied.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (Code number 453/2515). The authors would like to acknowledge Associate Professor Sarita Teerawatsakul from the Department of Epidemiology, for helping us with the study sample stratification. We would also thank the teachers and students from the six schools in Chiang Mai for their contribution and participation to this study.

References

- Dehue F, Bolman C, Vollink T (2008) Cyberbullying: youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychol Behav 11(2): 217- 223.

- Hutson E (2016) Cyberbullying in Adolescence: A Concept Analysis. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 39(1): 60-70.

- Pham T, Adesman A (2015) Teen victimization: prevalence and consequences of traditional and cyberbullying. Curr Opin Pediatr 27(6): 748-756.

- Garett R, Lord LR, Young SD (2016) Associations between social media and cyberbullying: a review of the literature. Mhealth 2: 46.

- Bottino SM, Bottino CM, Regina CG, Correia AV, Ribeiro WS (2015) Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Cad Saude Publica 31(3): 463-475.

- Selkie EM, Fales JL, Moreno MA (2016) Cyberbullying Prevalence Among US Middle and High School-Aged Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Quality Assessment. J Adolesc Health 58(2): 125-133.

- Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, et al. (2017) Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 7(1): 60-76.

- Lamb J, Pepler DJ, Craig W (2009) Approach to bullying and victimization. Can Fam Physician 55(4): 356-360.

- Landstedt E, Persson S (2014) Bullying, cyberbullying, and mental health in young people. Scand J Public Health 42(4): 393-399.

- Suzuki K, Asaga R, Sourander A, Hoven CW, Mandell D (2012) Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health. Int J Adolesc Med Health 24(1): 27-35.

- Moreno MA (2014) Cyberbullying. JAMA Pediatr 168(5): 500.

- Cenat JM, Hebert M, Blais M, Lavoie F, Guerrier M, et al. (2014) Cyberbullying, psychological distress and self-esteem among youth in Quebec schools. J Affect Disord 169: 7-9.

- Olenik-Shemesh D, Heiman T (2017) Cyberbullying Victimization in Adolescents as Related to Body Esteem, Social Support, and Social SelfEfficacy. J Genet Psychol 178(1): 28-43.

- van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J (2014) Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 168(5): 435-442.

- Sigurdson JF, Undheim AM, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Sund AM (2015) The long-term effects of being bullied or a bully in adolescence on externalizing and internalizing mental health problems in adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 9: 42.

- Boonchooduang N, Louthrenoo O, Charnsil C, Narkpongphun A (2017) Alcohol use and associated risk behaviors among adolescents in Northern Thailand. ASEAN J Psychiatry 18(2): 199-205.

- (2015) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2000) Manual for the ASEBA preschool form & profiles. Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT

- Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM (2000) The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev 21(8): 265-271.

- Tural Hesapcioglu S, Ercan F (2017) Traditional and cyberbullying cooccurrence and its relationship to psychiatric symptoms. Pediatr Int 59(1): 16-22.

- Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, Milne A, et al. (2015) Prevalence and Effect of Cyberbullying on Children and Young People: A Scoping Review of Social Media Studies. JAMA Pediatr 169(8): 770-777.

- Gkiomisi A, Gkrizioti M, Gkiomisi A, Anastasilakis DA, Kardaras P (2017) Cyberbullying Among Greek High School Adolescents. Indian J Pediatr 84(5): 364-368.

- Kim S, Colwell SR, Kata A, Boyle MH, Georgiades K (2017) Cyberbullying Victimization and Adolescent Mental Health: Evidence of Differential Effects by Sex and Mental Health Problem Type. J Youth Adolesc 47(3): 661-672.

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR (2009) School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J Adolesc Health 45(4): 368-375.

- Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP (2015) The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health 56(5): 483-488.

- Festl R, Quandt T (2016) The Role of Online Communication in LongTerm Cyberbullying Involvement Among Girls and Boys. J Youth Adolesc 45(9): 1931-1945.

Mini Review

Mini Review