Abstract

Child birth is a happy event in a family and procreation is the wish of every society. However, when a Child is born with health problems or dies, it is a moral and social burden for the community. Child mortality is decreasing elsewhere in our global society, there is a lot aim to be done in developing countries, the DRC included. The main goal of this research for Assessment Was to the abnormality of neonatal mortality at the Kenge area health During the period from 2013 to 2016. The study used a descriptive and analytical design was based sample of 84 757 Amongst Deaths Recorded at the health area Kenge During. The Above period. Results show an average rate of 2.1% early neonatal mortality with a prevalence of 1.3%. Besides, the mean-standard deviation ratio or “Z-score” Indicated que la variations of normal newborn Deaths Were Effectively During the four years of the study, except for dystocia deliveries. Prematurity, choke and infections may be among the most significant causes of child deaths. These determinants of neonatal mortality need to be taken in gravement Addressing the sustainable development goal No. 3 That Promotes maternal child health and wellbeing.

Keywords: Child Mortality; Determinant; Neonatality; Normal Distribution

Summary

The birth of a healthy child in a family is a happy event and procreation is as desired in each company. However, when the child is born with a health problem or died at birth, this causes a moral and social disruption in the community. Although it has been observed that child mortality is declining in most parts of the world, it is still a major problem in developing countries, including the DRC. The main objective of this study was to analyze the abnormality of neonatal mortality in the ZS Kenge in the period from 2013 to 2016. The study used a descriptive and analytical estimate based on a sample of 84 deaths on 757enregistrés in SZ Kenge during the above period. The results indicate that the average of the early neonatal mortality rate was 2.1% with a prevalence rate of 1.3%. Moreover, the average-standard deviation ratio or “Z-Score” indicated that variations in neonatal deaths were normal during the 4 years of study, except for obstructed labor. Prematurity, asphyxia and infections could be among the most significant causes of death.

These determinants of neonatal mortality were expected to be taken seriously in order to achieve the objective of sustainable de velopment No. 3 for the promotion of welfare and maternal health and child. the mean-standard deviation ratio or “Z-Score” indicated that variations in neonatal deaths were normal during the 4 years of study, except for obstructed labor. Prematurity, asphyxia and infections could be among the most significant causes of death. These determinants of neonatal mortality were expected to be taken seriously in order to achieve the objective of sustainable development No. 3 for the promotion of welfare and maternal health and child. the mean-standard deviation ratio or “Z-Score” indicated that variations in neonatal deaths were normal during the 4 years of study, except for obstructed labor. Prematurity, asphyxia and infections could be among the most significant causes of death. These determinants of neonatal mortality were expected to be taken seriously in order to achieve the objective of sustainable development No. 3 for the promotion of welfare and maternal health and child.

Introduction

Approximately 4 million births are recorded as neonatal deaths each year worldwide. ¾ of them occur in the first week of life with the risk in the first day. The main causes of this mortality are prematurity, respiratory distress and neonatal infection (WHO, 2010) [1]. Early neonatal mortality in neonatal units in poor countries hospitals may brush against the slaughter in excess of 50% [2]. The neonatal mortality rate is an indicator of the quality of obstetric and neonatal care. It depends on the level of socio-economic development of a country (WHO, 2013) [3].

For SANIFO Hope Foundation [4], 82% of newborn deaths are the 58 developing countries classified as high risk, and each year 2 million newborns die within 24 hours of their existence. In 2015, neonatal deaths accounted for 45% of total deaths, a proportional increase of 5% compared to 2000 (UNICEF, 2016 According to WHO (2005) [5,6]. Africa has the neonatal mortality rate estimated as high 45 deaths per 1,000 live births against 5 deaths in developed countries. for Madagascar for example, the demographic and health surveys data (DHS 2003-2004) indicate a neonatal mortality rate of 32 per 1,000 live births. these neonatal deaths account for 55% of infant mortality (Madagascar, 2004) [7]. The challenge is particularly important in our country, and especially in the health Kenge zone which is exposed to the morbidity and mortality of mother and child. Indeed, maternal, newborn and child is alarming and marked by maternal and child mortality are among the highest in the world, for a ratio of 549 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, a child mortality rate to 158 to 1000, an infant mortality rate 97 to 1000 and a neonatal mortality rate of 42 to 1000 [8]. Despite the efforts, the health of mothers and children remains a concern. This requires effective neonatal mortality reduction programs that consider the interventions on modifiable risk factors. Of such interventions will focus on economic and health measures useful for the survival of newborns. Health facilities at the primary level recorded in most cases of pregnant women with limited financial resources, that is to say a low socioeconomic level.

Status Report

Neonatal mortality is defined as the probability that a newborn will die between birth and 28 days of life. The last of the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in 2004 about 3.7 million children died during the first 28 days of life (WHO, 2004). This mortality risk experiencing tremendous changes during the neonatal period (UNICEF, 2008) [9]. Each year 2,000,000 babies die within 24 hours of their existence, 99% of these deaths occur in low-income countries. It lacks 350,000 midwives worldwide (Sanofi Espoir Foundation, 2013) [4]. In Africa 70% of the population lives in rural areas and 50% below the poverty line, while 90% of qualified personnel is devoted in large urban centers, and only 60% of women receive prenatal care, half of deliveries take place at home without medical assistance.

A midwife formed African supports 500 mothers each year. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is ranked among the countries with the least progress in child survival. Its mortality rate of children under five years has remained virtually unchanged for twenty years, from the late 1980s [10,11]. According to WHO [1] 158 1000 newborns die every day at birth in the DRC, where only 76 pediatricians are deployed to support a population represented by 20% of children. Based on data from MICS 2010 and EDS from 2005 to 2006 and from 2013 to 2014, we note that the situation of maternal, newborn and child remains alarming. It is marked by high maternal and child mortality are among the highest in the world, for a ratio of 549 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, a child mortality rate of 158 per 1,000, an infant mortality rate to 971,000 and a neonatal mortality rate of 42 per 1,000 (DRC, 2015; 2007) [12,13]. Despite the efforts, the health of mothers and children remains a concern in the Congo (DRC) as shown by the levels of the indicators collected during the investigation on the state places the health sector in April 1998 (DRC 2001) [14]. For infants, the risk factors are closely related to the health and future mothers’ conditions. The intrauterine growth restriction, which is defined by insufficient fetal growth during pregnancy is a major risk of perinatal death highlights UNICEF (2003) [15]. Underweight is associated with malnutrition and poor health of the mother. Neonatal mortality follows the “2/3 rule” i.e. 2/3 of infant deaths occur in the first month;

The causes of neonatal mortality as its most important factors to risk are two-fold: the causes and factors of maternal and fetal order, firstly, and secondly, obstetric risk factors and the causes and sociocultural. The fundamental maternal causes of neonatal mortality include congenital uterine malformations, the contracted pelvis, incompatibility maternal fetal rhesus. Risk factors related to the mother include illegitimate pregnancies, unfavorable working conditions and transport, low socioeconomic class and unmonitored pregnancies, age and parity (Nzoko, 2017) [16]. As for obstetric risk factors, they are for the most part related to pregnancy, including abnormalities in the evolution of pregnancy; premature rupture of the membrane and dystocia; colored amniotic fluid, etc. Finally, socio-cultural factors are behavioral and environmental conditions.

For example, neonatal mortality can be attributed to the difficult working conditions and transport, illegitimate pregnancies, which in turn can be explained by parental poverty that forces many women and girls into prostitution to survive (Rachidatou 2009). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [17] observed that the rates of maternal and neonatal mortality are very high in developing countries reason particularly low utilization of maternity services. The latter is dependent on poor reception and overbearing attitude of care providers, medical practices conducted routinely, not based on scientific evidence that can be dangerous and/or ineffective. Otherwise, the main causes of fetal neonatal mortality are infectious diseases including sepsis, pneumonia, tetanus and diarrhea in 36% of cases.

Premature births and complications attributable to that account for 27% of deaths, while neonatal asphyxia accounts for 23% of cases. Of the remaining 14%, 7% of all deaths are associated with a birth defect. From one year to another, prematurity presented in general more than 40% of neonatal deaths (UNICEF (2003) [15]. According to Nguyen Ngoc-study (2006) conducted in 6 countries and those Cissé [18] conducted Senegal, prematurity and its complications belong to three main causes of neonatal mortality in developing countries and occupies the first position, while asphyxiation comes second. The third position is occupied by respiratory distress. On the etiological, conditions usually responsible for respiratory distress of newborn are perinatal asphyxia by inhalation of amniotic fluid or resorption delay; pulmonary immaturity and perinatal infection; the affections of surgical origin [19]. To these different causes are added acute fetal distress is a condition that threatens the life, health and psychomotor future of the fetus and newborn. The characteristics of this suffering are: metabolic acidosis, persistent APGAR score below 3 beyond 5 minutes life; neurological consequences in the immediate neonatal period including seizures, hypotonia, coma, or hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, the obvious dysfunction of multiple organs in the immediate neonatal period (SANIFO Hope Foundation, 2013) [4]. Neonatal infection is a worldwide public health problem and is also among the causes of neonatal mortality. Its incidence is close to 1% of births in industrialized countries but higher in developing countries [20]. These infections are most often secondary to antenatal contamination by amniotic fluid, colonized from a germ from the vaginal flora. Three nuclei dominate neonatal bacterial infections: B Streptococcus, Listeria and Escherichia coli.

The B streptococcus is responsible for 25 to 40% of infections of the newborn and over half of maternal-fetal infections (Nguyen Ngoc-2006) [21]. To these different causes befits add birth defects, the most common being the polymalformations, cleft palate (cleft lip and slots), and cleft lip (cleft lip) followed by congenital heart disease, malformations in small proportions but as serious digestive malformations, hydrocephalus and anencephaly. Originally hypoxia and anemia, placenta previa is also cited among the causes of fetal neonatal deaths (UNICEF, 2003) [22].

Materials and Methods

Description of the Study Environment

Our study is among the Rural Health Zone (Kenge Kenge ZS). She is one of 14 health zones of the Provincial Health Division Kwango (DPS-Kwango). The health zone covers an area of 5559 km2 on the 89,458 km2 that account Province Kwango. The ZS Kenge has a population of 300,207 inhabitants with a density of 54 inhabitants / km2 divided into 28 health areas of 28 health centers each, while the provincial density was 28 inhabitants / km2 in 2014 (DPS Kwango, 2018) [23]. The Kenge health zone was delineated in October 1984, in the former province of Bandundu, in the first the first regional conference on the promotion of care. The ZS Kenge is currently found in the Province of Kwango and specifically in the town of Kenge. It is located 275 km from the city of Kinshasa, on National Highway No. 1 (Kinshasa-Kikwit).

It is bounded to the north by the Kikongo health zone and Bonga-Yassa, south by the Kimbao health zone and Moanza, to the west by the Boko health zone, to the east by the Health Zone of Masimanimba (City of Kenge, 2018) [24]. Province Kwango along with wide a tropical climate zone with two rainy seasons (September- January, and March-May) and two dry seasons (May to September; January-March). This partly explains the presence of the herbo-boiseuse savannah. The City of Kenge is entirely on plateaus intersected by valleys, and sometimes the hills between Wamba rivers to the west and east Bakali (Figure 1). The soil is sandy type Kenge Kalahari Karoo. The vegetation consists mainly of grassland, woodland and gallery forests found along rivers. Populationthe ZS Kenge is 80% rural and agricultural activities are the main source of income. The trading companies also provide employment in the trading areas, small and medium enterprise, mototaxis well as education, health and public administration. This population is essentially from the Yaka ethnic group but can be cosmopolitan in urban areas. It includes the populations of ethnic groups and tribes Yaka Pelende, Mbala, Suku, Hungani, Kongo, Ngala, Swahili and phones. The Pelende tribe is the majority in the health areaed [25]. Kwango in general, and Kenge Health Zone in particular, lags behind in almost all areas are among the most affected by neonatal mortality provinces. In 1984, only 13 doctors had charge of the entire district, a doctor for more than 65 000 inhabitants, on an area covering about 97 000 km2 . The territories of Kasongo Lunda and Kenge proved particularly poor. Depending on whether one considers the official population estimates or projections for the year 2006 on the basis of electoral lists, that represents barely one doctor for more than 186 000 inhabitants or doctor for 114,000 people instead of 5000 recommended persons [25].

Sampling Method and Techniques Data Collection

Methods and Data Collection Techniques: This study is to identify the causes of neonatal mortality in the ZS Kenge in the period from 2013 to 2016. The study used an analytical method on a non-random sample of 84 comprehensive neonatal deaths of 757 registered in the ZS Kenge during the above period. The choice of non-probability sampling method but comprehensive was dictated by the occurrence random cases of neonatal deaths. As for the data collection techniques, the study is based on data from a surveysanitary Quantitative cross descriptive and analytical estimates. Data collection instruments were the registry, partographs mothers who gave birth to dead babies and newborns sheets died before the 7th day of their births.

Selection Criteria: Before including a child in the study sample, the researchers considered two following criteria:

a) newborns died in the maternity;

b) newborns died on the 7th day before the 7th day of birth in the service of pediatrics and health centers.

Exclusion Criteria: Were excluded from the sample this study, all new life born, and newborns died after 7 days of their births.

Data Analysis Techniques: The study made use of descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze thefrom datapartographs and cards containing the ad hoc information. Descriptive statistics alloweddetect the prevalence of neonatal mortality through thecalculation of the frequency, mean, mode, median, standard deviation, and the Z-score. The calculation of the frequencies has been to describe the sample workforce by age and sex based on Equation 1:

Or,

Relative frequency f =

FO = Observed frequency

FA = expected frequency

The statistics Z (Z-score) has been used to derive the sample normalcy comparing the average obtained in the following the standard differential Equation 2:

Or,

= Respectively from the sample and that of the population for N observations of the variable x, if obtained according to Equation 3: X et µµ = 0

σ = Standard deviation of the variable x medium X obtained according to Equation 4:

Inferential statistics was essentially based on the hypothesis test average. The statistics Z was testede at the 5% significance level (p = 0.05), using computer software SPSS 12.0 and MS Excel 2010, for detect neonatal mortality normality of the following assumptions:

H0: = 0, the reference population is not normally distributed since there is noμμ

H1: ≠ 0, the reference population is normally distributed as is and it is significantly equalμμat the average of the sample.

After this test, the reference population was declared normally distributed if the null hypothesis was rejected95% confidence level (withaz-score greater than or equal to 1.96) or 99% confidence level (with a z-score greater than or equal to 2.58). Below a z-score of 1.96, the reference population was declared abnormally distributed. It was in that time that could declare abnormal neonatal mortality in the ZS Kenge.

Analysis Results

This study has identified both the prevalence of neonatal mortality and its root causes in Kenge health zone during the period from 2013 to 2016.

Prevalence of Neonatal Mortality in the Health Zone Kenge

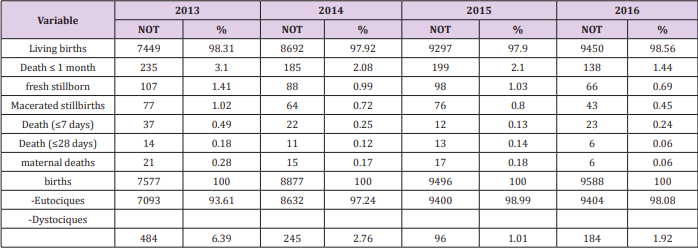

Prevalence of Neonatal Mortality in Kenge: Neonatal mortality is a real problem in the health zone of Kenge. Looking through the statistics of the 2013 to 2016 area, we found that a total of 35,538 births there are 34,529 and 1,009 eutocia dystocia. Neonatal deaths this amounted to 757 during the same period 2.1%. In 2013, there were 7577 births including 235 deaths 3%. In 2014, 8,877 births including 185 deaths or 2.08%. In 2015, 9,496 births including 199 deaths and 2.1% in 2016, including 138 deaths 9588 births is 1.44%. Of all deaths in the year 2016, we noticed the following: 0.69% of infants died at birth; 0.45% were born macerated; 0.24% died before the 7th day of birth; 0.06% are deaths before 28 days after birth (Table 1).

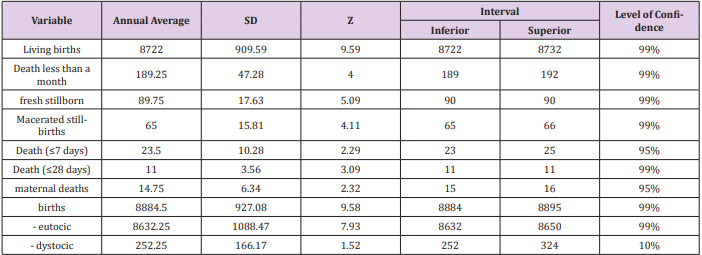

Normality of Neonatal Mortality in Kenge

According to the analysis of Table 2 that all variables under study had normal statistical distribution, at except dystocia whose Z statistic was less at1.96. Other variables were normally distributed to 99%, except death or more than 7 days and maternal deaths were normal at 95% (less than Z at 3 but greater than 2). Thus, the recorded annual average between 2013 and 2016 rotates about 8632 eutocic deliveries (Standard Deviation = 1089; Z = 7.93) and 252 dystocia (SD = 166, Z = 1.52) with 8722 live births (Standard Deviation = 910, Z = 9.59). Regarding the deaths, there were 90 stillbirths costs (SD = 18, Z = 5.09), 65 macerated stillbirths (SD = 16, Z = 4.11), 24 deaths ≤7 jrs (SD = 10, Z = 2.29), 11 ≤28 dys death (SD = 4, Z = 3.09) and 15 maternal deaths (SD = 6, Z = 2.32).

Discussion of Results on Neonatal Mortality in Kenge

The figures on the prevalence of neonatal mortality in the ZS Kenge indicate slight deviations from the national and regional averages in Africa. Balaka et al. [26] present a bleak picture of the university hospital of Lome (Togo). Nagalo and Dao [27] indicate that the morbidity and mortality of infants in hospital center of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) was of the order of 91 deaths or 13.1%, respectively Chelo et al. [28] report that in Yaoundé, the mortality and morbidity is 0.5. In the same line of ideas Cissé et al. [29] present a comprehensive high neonatal mortality rate of 50 deaths (for infant morbidity) and 50 deaths in 1000 (for infant mortality in Dakar (Senegal) and neonatal mortality early 45.5 per 1,000.

Therefore, neonatal mortality should be a major concern of African governments, especially in the confines of the remotest territories. It can be considered as an indicator of how treatments are given to newborns in a facility. In the absence of reliable statistics on fetal deaths, neonatal mortality is one of the indicators of development of a given community and reflects the quality of obstetric and neonatal care in a health facility. It is therefore necessary to see our health zones to bring well-equipped neonatal units to deal with this gangrene (Cissé et al. 1996). Community animators of reproductive health sector must work harder to reduce the exposure of pregnant women and new mothers about the most recurrent risk factors, including obstructed labor, premature rupture of membranes, the ‘maternal age, parity, education level, underweight, gestational age and pathologies during pregnancy (WHO, 2005; Berthin 2004; UNICEF, 2003; WHO 1997) [7,15,20,31-37].

Conclusion

The descriptive and analytical design used in this study to determine the normality of neonatal mortality in Kenge health zone to help reduce early mortality of our children. It is proposed to answer the question of whether neonatal mortality was normal or abnormal in that area. The target population consisted of infant’s dead children from birth until the 7th day of birth between 2013 and 2016 in Kenge health zone. The total population was 757 cases and the sample of 84 cases. The results of the analysis indicate that 97% of births were eutocic against 3% dystocic; 7 to 14 per 1,000 births are stillborn and 5 to 10 births are born dead macerated. There were also between 1-5 deaths from roughly 7 days and at least 2 deaths of roughly 28 days 1000 deliveries in the study period. Under-average standard deviation quotient, commonly known by the name “Z-Score” or “statistical Z”, variations of newborn deaths led to conclude that they were normal during the 4 years of study, except for obstructed labor. And neonatal mortality was established around 1.3% or 13 deaths from less than one week in 1000 births. changes in newborn deaths led to conclude that they were normal during the 4 years of study, except for obstructed labor. And neonatal mortality was established around 1.3% or 13 deaths from less than one week in 1000 births. changes in newborn deaths led to conclude that they were normal during the 4 years of study, except for obstructed labor. And neonatal mortality was established around 1.3% or 13 deaths from less than one week in 1000 births.

Recommendations

Neonatal death is a problem that does not only concern the health staff but also parents and administrative authorities. Among other things, we recommend politico-administrative and health authorities to provide hospitals and health centers with adequate means to intervene in time on women in labor and delivery and or newborns with serious risk of death. Medical personnel, we recommend observing the rules of asepsis during delivery and standards of the refocused prenatal visit. They have to ensure good care for sick newborns and premature.pregnant women and new mothers to reduce their exposure to promiscuity and to voluntarily accept public action to promptly adhere to the instructions of the health authorities, including the start time of the EIC, compliance with appointments, the personal and food hygiene, ect.

The Ministry of Health will instruct the provincial health authorities to ensure the risk factors for neonatal mortality in the most remote health facilities in each province. These includeobstructed labor, premature rupture of membranes, maternal age, gender, educational level, underweight, gestational age and the pathologies during pregnancy. This is how they can facilitate the implementation of the national policy of waiting 0% of neonatal mortality. It goes without saying that such action can only succeed if health areas are strongly committed to support health structures in terms of staff training, and monitoring and evaluation of the practical implementation of the national policy on fight against infant mortality in the DRC.

Suggestions for Future Research

This study was unable to determine the real causes and risk factors targeted by policies in the ZS Kenge. Such study will determine the causes of the normality of neonatal mortality in the health area. It will validate the suspected risk factors such as maternal age, parity, education level, obstructed labor, premature rupture of membranes, sex, underweight, gestational age. It is also important to assess the socio-economic and spatial factors affecting the accessibility of pregnant mothers in the NPC and SPC services to facilitate distribution and equipping neonatal units throughout the whole of the Republic.

Thanks

We acknowledge all those who provided their valuable contributions to various levels drafting of this article, including the anonymous reviewers, secretaries and members of the editorial board of this special edition and its academic editor. We are particularly grateful to the Academic Secretary General of the “Higher Institute of Medical Technologies - Mary Queen of Peace Kenge (ISTM-MRP Kenge)” Prof. Dr. Cush Ngonzo Luwesi for having informed us and motivated to write this publication.

Author Contributions

This research is part of the license memory the Assistant Wivine Nzoko Ngana, memory realized Division of Nursing ISTMMRP Kenge, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), during the academic year 2016 -2017, under the direction of Prof. John Inipavudu Baelani and Head of Works Dr. Chiara Castelani. The authors much appreciate their contributions and those of the other co-authors in finalizing this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest in this study, because no donor or investigated has played a leading role in the interpretation of study results. The writing of the manuscript and the decision to publish exclusively the responsibility of the author.

References

- (2010) WHO Bulletin of the WHO health. WHO Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Bezzaoucha A Kebboul A, El Kebboub A, Aliche A (2008) The evolution of neonatal mortality at the University Hospital of Blida (Algeria), from 1999 to 2006. In Blondel B, Breart J 103(1): 29-36.

- (2013) UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, United Nations. 2013 Report: Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Secretariat of UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland.

- (2013) Sanofi Hope Foundation Award for Midwives. Fight against infant mortality in developing countries. London, United Kingdom.

- (2016) UNICEF: 70 years for each child - The situation of children in the world. Secretariat of UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland.

- (2016) UNICEF: 70 years for each child - The situation of children in the world. Secretariat of UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Berthin A (2004) Factors of early neonatal mortality in obstetrics gynecology CHU Befelatanana. of final dissertation. National Institute of Public and Community Health, Antananarivo, Madagascar.

- (2012) DRC Democratic Republic of Congo Standards for health zone on integrated interventions for maternal health, newborn and child in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Secretariat General for Health, Kinshasa, DRC.

- (2012) DRC Democratic Republic of Congo Standards for health zone on integrated interventions for maternal health, newborn and child in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Secretariat General for Health, Kinshasa, DRC.

- Nzoko NW (2017) Problems of neonatal mortality in Kenge health zone (2016-2017) License Memory Education and Nursing Administration. Division of Nursing, ISTM-MRP Kenge Kenge, DRC.

- (2014) Save the Children: The situation of the World’s Mothers 2014 Saving mothers and children in humanitarian crises. London, United Kingdom.

- (2015) DRC Democratic Republic of Congo Second Demographic and Health Survey (DHS-RDC II 2013-2014) MINIPLAN and MOH, Kinshasa, DRC.

- (2007) DRC Democratic Republic of Congo Demographic and Health Survey (DHS-RDC I 2005-2006) MINIPLAN and MOH, Kinshasa, DRC.

- (2003) UNICEF Opportunities for every newborn in Africa. Secretariat of UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Nzoko NW (2017) Problems of neonatal mortality in Kenge health zone (2016-2017) License Memory Education and Nursing Administration. Division of Nursing, ISTM-MRP Kenge Kenge, DRC.

- (2000) Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Session: The humanizes care. Olath and Liverpool Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK.

- Cissé CT, Yacoubou Y, O Ndiaye, R Diop Mbengue (2006) Changes in early neonatal mortality between 1994 and 2003 at the University Hospital in Dakar. National School of Public Health, Dakar, Senegal 35(1): 46-52.

- Geneviève (2002) Proposal Paper for the 21st century - Reproductive health and public policy. Research Unit in Reproductive Health and Society, Institute of Research for Development (IRD) in Montpellier, France.

- Gentilini Mr, Duflo B (1992) Tropical Medicine. Ed. Flammarion Medecine-Sciences, Paris, France.

- (2018) DPS, Provincial Directorate of Health Kwango Health Screenings 2018. DPS -Kwango, Kenge, DRC.

- (2018) City of Kenge Kenge administrative Census 2017: Mayor of the City of Kenge, Province Kwango DRC.

- Omasombo J Zenga J William L M’pene Z, Mr Zana, Edwine S, et al. (2012) Kwango, the Land of Bana Lunda. Ed. The Scream, Tervuren, Belgium.

- (2013) UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, United Nations. 2013 Report: Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Secretariat of UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Balaka B, Agbere AD, And Kpemissi E (1998) The evolution of early neonatal mortality in 10 years 1981-1982, 1991-1992, at the University Hospital of Lome. What health policy for tomorrow? Journal of Medicine in Black Africa.

- Nagalo K, Dao F (2013) Morbidity and mortality of newborns hospitalized on 10 years at the El Fateh Suka Clinic, Ouagadougou. of final dissertation. University of Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

- Chelo David Francisca Monebenimp (2008) Neonatal mortality and its determinants in a tertiary maternity in Yaoundé. National Statistics Institute, Yaounde, Cameroon.

- Cisse CT Martin SL, Ngoma SJ (1996) Early neonatal mortality at the maternity of the CHU of Dakar: current status and development trends between May 1987 and 1994. Journal of Medicine in Black Africa.

- (2013) SEED. Knowledge Attitude and Practice Survey Mbujimayi. Kinshasa: Secretariat of the Ministry of Planning, DRC.

- Lawn JE, Cousens SN Zupan RL (2013) Lancet Neonatal Survival steering team + 4000000 Deaths When, Were, why?

- (2005) WHO The survival of the newborn. WHO Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland.

- (1997) WHO, UNESCO, UNICEF Facts for Life. WHO Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Luwesi CN (2018) How the changing environmental trends lead to chronic undernutrition and foodshortage in Kenge Municipality, DRC. Proposal Submitted to The Friedman School of Nutrition at Tufts University, USA and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK.

- Moulkhaloua Belkheir NS (2016) Neonatal mortality. Abubakr Belkaïd University, Tlemcen, Algeria.

- Amon Tanoh Dick F, JP Yenan, Lasme Guillao E, Akafou AE, N’Guessan AR, et al. (2009) neonatal mortality risk factors in a tertiary hospital in Abidjan (Ivory Coast) African J Anesthésie- Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine.

- (2007) WHO Neonatal mortality in the Region Eastern Mediterranean determinants and strategies for achieving the fourth Millennium Development. Technical document. WHO Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Papiernik E, Pons JC, Goffinet F (2003) Prevention of prematurity. Flammarion medical science, Paris, France.

- Ravaoarisoa, Matangtoy, Rakotonirina. (2011) Determinants of early neonatal mortality in maternity Bafelatanana, Antananarivo. African Journal of Anesthésie.

- Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine.

Research Article

Research Article