Abstract

Hydrocephalus consists of a clinical entity characterized by accumulation of fluid in the cerebral ventricles and in the subarachnoid space. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPHP) is a neurological syndrome usually characterized by a clinical triad: gait apraxia, dementia and urinary incontinence, associated with ventriculomegaly (radiologically detected by cranial tomography and / or magnetic resonance imaging) and normal cerebrospinal fluid. However, the absence of one or more of these symptoms does not rule out the diagnostic hypothesis of hydrocephalus, as observed in the case in which the patient presented only urinary incontinence and auditory hallucinations. Hydrocephalus is primarily a manifestation of some underlying morbid state, such as tumors, infections, or intracranial hemorrhages. The fact that auditory hallucination is not an initial symptom and does not form part of the diagnostic clinical triad, demonstrates the importance of anamnesis and the correct documentation of the case when it is associated with the patient’s age, absence of trauma or absence of any other cause of hydrocephalus. The objective of this study was to describe a clinical case of a young patient presenting with psychotic symptoms and hydrocephalus and, more specifically, to promote the discussion of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in adults. It was possible to conclude that the follow-up of the case, from the initial approach to the implemented therapy, was, in general, consistent with what the literature describes. Failure to perform additional tests, which are difficult to access, did not prevent the success of the treatment and the clinical improvement of the patient.

Keywords: Hydrocephalus; Psychotic disorders; Insanity; Urinary incontinence

Introduction

The assessment of a psychotic patient requires consideration of the possibility that psychotic symptoms (i.e., delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, markedly disorganized or catatonic behavior) result from a general medical condition such as a brain tumor or substance ingestion, such as phencyclidine (PCP) or a medicine, such as cortisol [1]. There is scarce relevant epidemiological data on psychotic disorder caused by a general medical condition or by induction of substances.1 These disorders are more commonly found in patients who abuse alcohol or other substances in the long run. On the other hand, delusional syndrome that can accompany complex partial seizures is more common in women [1]. Physical conditions, such as brain neoplasms, may occur in hallucinations. Sensory deprivation, as occurs in blind or deaf people, can also result in delusional or hallucinatory experiences.1 In addition, it is related to the temporal and other brain regions, especially the right hemisphere and the parietal lobe, being associated with delusions [1].

Psychoactive substances are more common causes of psychotic syndromes.1 The most frequently involved are alcohol, indolic hallucinogens, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), amphetamine, cocaine, mescaline, phencyclidine, and ketamine. In addition, many other substances, including steroids and thyroxine, can produce hallucinations [1]. The diagnosis of psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is defined by specifying the predominant symptoms. When the diagnosis is used, the medical condition should be included along with the predominant pattern of symptoms (eg, psychotic disorder due to a brain tumor with delusions). [1] The disorder does not occur exclusively while the patient is in delirium or dementia and the symptoms are not well explained by another mental disorder. Hydrocephalus, in turn, consists of a clinical entity characterized by accumulation of fluid in the cerebral ventricles and the subarachnoid space. This accumulation can occur due to an imbalance between synthesis and resorption or by some obstruction that prevents its circulation and drainage. [1] Cerebrospinal fluid, acts as a protector of the central nervous system (CNS) by reducing the impact on the brain and spinal cord, and carries essential nutrients to the CNS, maintaining the intra-cranial pressure (ICP) [2].

Taking into account the possible causes of hydrocephalus, it can be classified as obstructive, non-obstructive hydrocephalus and idiopathic normal pressure [3]. The obstructive occurs when there is an obstacle to the circulation of the spinal fluid, commonly due to stenosis of the Sylvius aqueduct. In non-obstructive hydrocephalus, the spinal fluid circulates freely, however, reabsorption is mostly impaired by intra-cranial bleeding. Finally, idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus has no specific cause. spinal fluid is retained in the cerebral ventricles, dilating them and causing compression of the brain structures [3]. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (HPNI) is a neurological syndrome usually characterized by a clinical triad (gait apraxia, dementia and urinary incontinence), associated with ventriculomegaly (radiologically detected by cranial tomography and / or resonance) and normal cerebrospinal fluid [2].

The literature reports a limited number of epidemiological studies on idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. The reported incidence varies from 1.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants to 2.2 cases per 1,000,000 inhabitants. It is estimated that 1.6% to 5.4% of patients with dementia are caused by PNyRP [3]. Hydrocephalus is a morbidity of extreme importance for neurosurgery and for the whole medical society, due mainly to the great range of diseases to which it can associate, the number of surgical procedures within the total volume of the specialty and the virtual sequels to which the hydrocephalus occurs primarily as a manifestation of some underlying morbid state, such as tumors, infections or intracranial haemorrhages, for example [3]. Most of these diseases typically affect the extremes of age, children and the elderly, not being common in young adults. This fact justifies this work and makes it important to describe this clinical condition in a young patient who developed psychotic symptoms concomitantly with hydrocephalus diagnosed by nuclear magnetic resonance of the skull, without obvious cause. Thus, the objective of this study was to describe a clinical case of a young patient presenting with psychotic symptoms and hydrocephalus and, more specifically, to promote the discussion of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in adults.

Case Report

Female patient, 26 years old, born in Vassouras-RJ, divorced, protestant, brown, completed high school and is a professional maid. She denied allergies, smoking, alcoholism and use of medications. She had no comorbidities, no family history of neurodegenerative, neurological or psychiatric disorders. She began sporadicly 03 years ago, a condition of auditory hallucinations, without distinction of the spoken content. She also denied any other kind of false sensory perception, claiming to remain vigilant and alert. After a few months presenting the hallucinations, she noticed an increase in voiding volume, even presenting diurnal urinary incontinence. She denied nocturnal enuresis, progressing to incapacitating holocronial headache associated with an alleged complex partial convulsive crisis (she said to be “aerial” and “deglutting”, but conscious). In the post-ictal period, there was a significant worsening of the headache.

She reported that she did not seek medical help initially because she related the symptomology to marital and spiritual problems. However, with the persistence of symptoms, she sought the Family Health Strategy (ESF) of her neighborhood, where she was referred to specialized care with a neurologist who requested an electroencephalogram (EEG) and prescribed carbamazepine 200mg, 3 times a day. The EEG showed the presence of isolated acute waves in the frontal and central regions bilaterally with predominance on the right.

Without diagnostic elucidation, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the skull was performed in December 2016. MRI showed a marked presence of supraententorial hydrocephalus, mild transependimary cerebrospinal transudation, ventricular dilation upstream (probably obstructive), with no infarct areas recently. After the diagnosis of hydrocephalus, she was referred to the neurosurgical approach and installation of ventriculoperitoneal shunt (DVP) at the Federal Hospital of Lagoa (Rio de Janeiro) in March 2017, where she was hospitalized for 9 days without major intercurrences.

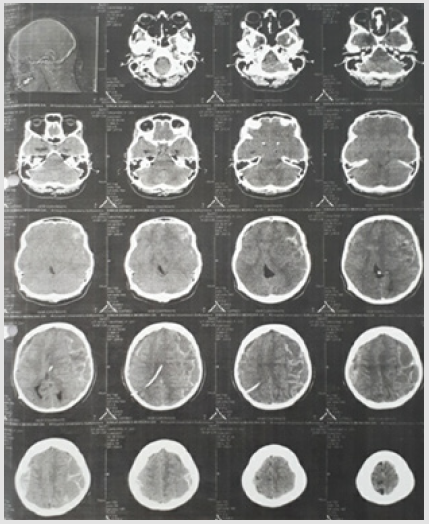

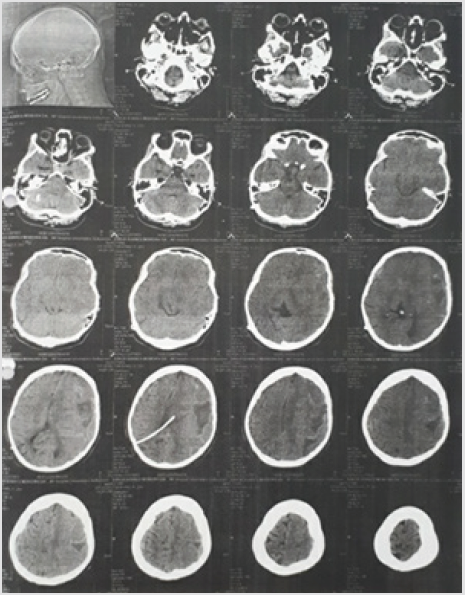

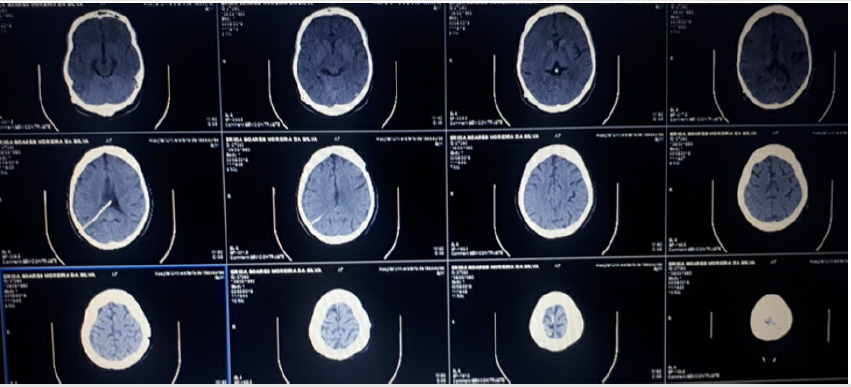

The patient remained asymptomatic for 2 months, when she began to present somnolence and headache. As a result, she sought out the neurology service, where a CT scan of the skull was requested. CT was performed on June 12, 2017 at the University Hospital of Vassouras (HUV), evidencing subdural hematoma (Figure 1). On the same day, a neurosurgeon was contacted who indicated hospitalization and referral to the referral hospital. Due to the persistence of the subdural hematoma (Figure 2) and it was not possible to transfer to the hospital of origin, we opted for the neurosurgical approach of drainage in the HUV itself. Without intercurrences, the patient was discharged on July 4 of the same year. The next day she was discharged (July 5), she was admitted to the emergency room of the HUV presenting with disorientation, drowsiness, jet vomiting, headache and muscular weakness. It was then evaluated by the neurosurgeon who suggested hospitalization in the infirmary bed. Furosemide 80 mg and diamox 250 mg 4 times daily were prescribed and her companion was instructed to perform manual drainage of the valve. Conservative treatment was maintained until July 10, when the patient was surgically treated. The patient was discharged on July 14, and was asymptomatic. A new CT scan of the skull was requested for August 2017 (Figure 3), followed by return referral to the neurosurgery clinic. The patient in question has been asymptomatic for 20 months, using carbamazepine 200 mg once a day and annual follow up with the neurosurgeon.

Figure 2: Computed Tomography of the Skull Performed on 06/28/2017 Evidencing Persistent Subdural Hematoma after Conservative Treatment.

Figure 3: Computed Tomography of the Control Skull Performed in August 2018 with presence of Dvp Without Hematoma and / or Edema.

It is in good general condition, lucid and oriented in time and space, being able to walk, stained, hydrated, acyanotic, anicteric, afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Featuring a ventriculoperitoneal shunt valve in the skull. Cardiovascular system: regular heart rhythm in two times, normofonetic sounds, without blows or extrassistoles. Respiratory apparatus: universally audible ve sicular murmurs without adventitious sounds. Abdomen: atypical, hydroaeuric noises present, tympanic, painless to superficial or deep palpation. Extremities: without edema, free calves, symmetrical and palpable pulses. Neurological examination: Glasgow Coma Scale: 15/15, isofio-reactive pupils, with no evident changes.

Discussion

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (PNH) can be divided into two categories: secondary and idiopathic. Secondary PNH occurs following underlying neurological events, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage (HSA) and intraventricular hemorrhage caused by tumors or ruptures of aneurysms and meningitis. In contrast, idiopathic PHN usually occurs between the sixth and eighth decades of life and does not yet have its pathophysiological mechanisms completely defined [4] Taking into account what is present in the current literature on the topic1, it is perceived that the case reported in this work is an atypical presentation of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, since the patient started the symptomatic condition with only 24 years old, differently from the usual age group reported in the literature In addition to this, the primary manifestation with psychotic symptoms stands out. Although most of the published works on the subject do not mention the description of psychiatric symptoms in patients with hydrocephalus, these have become more common in recent years [5]. Depression, anxiety and psychotic syndromes are mainly reported. Patients with PNH may develop symptoms with frontal predominance, such as personality changes, anxiety, depression, psychotic syndromes, obsessive compulsive disorder, Othello syndrome, theft and mania [5].

The HPNI-related guidelines provide specific criteria for the clinical diagnosis of the disease, and may, from these criteria (history, neuroimaging, clinic and physiological tests of the patient) classify the diagnosis as probable, possible and unlikely [6]. To be classified as probable, patient history must include: insidious involvement, origin after age 40, minimal duration of 3 to 6 months, no evidence of antecedents such as head trauma, intracerebral hemorrhage, meningitis or other known condition of hydrocephalus neurological / psychiatric condition that is sufficient to explain the presence of the symptoms. [6] Neuroimaging examinations, performed after the onset of symptoms, should show evidence of ventricular increase not entirely attributed to cerebral atrophy or congenital augmentation ( Evans index ≥ 0.3), no macroscopic cerebrospinal fluid obstruction, and at least one of the supportive features as an increase in temporal cortices of the lateral ventricles, not entirely attributed to hippocampal atrophy. A change in the water content of the brain (including periventricular signal changes in CT and MRI) that is not attributed to ischemic microvascular changes or demyelination and altered aqueduct flow or of the fourth ventricle. At the clinic, gait disturbance findings should be present, at least one area of change in cognition and urinary symptoms, or both. Regarding physiological assessment, the cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure, determined by lumbar puncture or a comparable procedure, should be in the range of 105-190 mm H2O, and appropriate pressure measurements greater or less than this range are not consistent with diagnosis of probable PNH

In the classification as NPH possible, the patient may present onset of recent or indeterminate, at any age after childhood, duration of less than three months or indeterminate, followed by events such as head trauma, remote history of intracerebral hemorrhage, childhood meningitis or in adolescence or other conditions. It is also permissible for PNH to coexist with another neurological, psychiatric or general condition, but which, in the evaluation of the clinician, is not entirely attributed to these conditions and is not progressive or clearly progressive [7]. In addition, a neuroimaging presenting an increase in the ventricles (but associated with evidence of cerebral atrophy, with severity sufficient to explain the size of the ventricle) and structural lesions that may influence it, symptoms of incontinence and / or cognitive alteration in the absence of gait disturbance or balance and physiological assessment of the unavailable opening pressure or results at the extremes of the expected rate of change (60-104 or 191-240 mm H2O) are also consistent with NPHs possible [7].

Finally, NPHL is considered unlikely when there is no evidence of ventriculomegaly when there are signs of increased intracranial pressure such as papilledema when no component of the clinical triad of PNH is present when cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure values are outside of the variations of “possible” NPHP (<60 or> 240 mm H2O) and when the symptoms are explained by other causes [8]. In elucidating the history of the case, the clinician should pay particular attention to how the symptoms (acute and subacute), their temporal (static, progressive) and their severity (mild, moderate, severe) have started. Emphasis should be given especially to symptoms involving gait, balance, cognition and urinary incontinence. The family occurrence of PNH is rarely observed (in contrast to congenital hydrocephalus). However, it is recommended that elements of family history be obtained, with emphasis on neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease, as well as other neurological and psychiatric conditions that have a hereditary character [8].

Despite the importance of clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of PNH, the degree of certainty provided only by clinical diagnosis related to the patient’s improvement after the implantation of a cerebrospinal fluid system varies from less than 50% to 60% [9]. Therefore, since such surgery is an invasive procedure that can lead to complications, especially in elderly patients, such as those with PNH, it is necessary to use additional tests (lumbar puncture, infusion test, external lumbar drainage, and evaluation of the volume of cerebrospinal fluid in the aqueduct of the midbrain). These tests have the purpose of confirming the diagnosis, identify which patients have a greater chance of improvement after the surgical intervention and more accurately predict the probability of this improvement [10] Analyzing the above and confronting the clinical and diagnostic follow-up of the patient whose case was reported in this study, we realized that this is a possible HPNI diagnosis, considering that it does not have all the criteria to fit as a probable HPNI. It reinforces the fact that the patient started the symptoms before the age of 40, had symptoms of urinary incontinence and had no gait disturbances. It is also noted that not all tests (mainly supplementary tests) were performed. In spite of this, the diagnosis was aptly closed considering only history, clinical examination and neuroimaging.

In a previously published study [9], the authors reported that 50% to 60% of patients who improve their symptoms with PVD are diagnosed with PNH. This fact reaffirms the need for additional tests before the patient is submitted to neurosurgery, taking into account all the present risks [9]. It was clear in the case in question that physicians did not use these tests, perhaps because they did not evaluate the need for them, since the clinic and neuroimaging already subsidized the diagnosis. However, even with the clinical improvement of the patient after the DVP, it is worth mentioning that the additional tests are essential with respect to the therapeutics and the prognosis. The adequate choice of therapy against a patient with PNH is primarily intended to restore the functional capacity of the patient. Therefore, the decision about when a surgical intervention should be performed necessarily depends on the use of tools that predict post-surgical outcome.

In addition to the supplementary tests discussed above, there are other indicators (favorable and unfavorable) that can be used. Favorable indicators of post-surgical improvement include the early onset of walking disorder and onset of symptoms in less than 6 months. Unfavorable indicators include absence of gait disturbance or onset after dementia onset, early onset of dementia, moderate to severe dementia, presence of dementia for more than two years, diffuse atrophy, and significant impairment of the white matter in the examination of magnetic resonance imaging [11]. As in any other disease, the choice of therapy should always be based on the risks and benefits, and in these cases, complementary tests become important tools to support this choice. Even considering the clinical improvement of the patient, the decision not to request complementary tests is questionable or questionable, since they help in the choice of therapy. Probably, in the case reported this happened because it is an atypical case, in a young patient, without comorbidities or still, for not being able to perform them.

The implantation of a system of cerebrospinal fluid by surgical intervention is the most used therapeutic measure for PNH. It is performed to relieve excess cerebrospinal fluid within the ventricular system and has demonstrated important benefits. Different types of cerebrospinal fluid derivation are used, but the most common is DVP, through the use of a thin catheter, whose internal flow is unidirectional (craniocaudal), due to the presence of a valvular device coupled to the system, which communicates the cerebral ventricles with the peritoneal cavity, where the excess of cerebrospinal fluid is drained. The efficacy of PVD ranges from 33% to 90%. This great disparity occurs due to the variation in patient selection in different studies and to the fact that there is no single scale for analysis of patient improvement that is universally accepted [4-6]. The third endoscopic ventriculostomy (ETT) has also been used in the treatment of PNH. Considered as an internal bypass, this technique consists of fenestration of the floor of the third ventricle, allowing the cerebrospinal fluid to pass directly from the third ventricle to the anterior compartment of the inter peduncular cistern, increasing the ventricular output systolic flow (which results in decreased excess of intraventricular cerebrospinal fluid) and decreasing the deleterious effects of cerebrospinal fluid on the ventricular walls during pulsed systolic waves [11].

Other examples of derivation that are rarely used include ventricular- atrial shunt and DLP. The rate of significant complications (severe intraoperative hemorrhage, subdural hematomas, neurological deficits, epilepsy, cardiac arrhythmias, hypothalamic dysfunction, cystic fistulas, infections) occurs in approximately 6% of patients after surgery [12]. The implantation of a derivation for cerebrospinal fluid drainage are varied and what will guide the choice will be, mainly, the professional experience. The results regarding the postoperative responses are similar and the complication rates are also similar, being the choice, therefore, at the discretion of the neurosurgeon. In the patient of the case, a choice was made for ventricular- peritoneal shunting. As for the postoperative period, the patient had a good response. However, two months after the procedure, he presented a subdural hematoma that had to be drained surgically, since he did not respond to conservative treatment. One day after the approach, the subdural hematoma had to be reopened, with no other complications. When the diagnosis is made early and the appropriate therapy is also implanted early, the results are very favorable, the prognosis is good, and patients return normally to their activities.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that PNH is a potentially treatable condition characterized by gait disorders, cognitive alteration and urinary incontinence, and should be included in the differential diagnosis even in young patients, despite its prevalence in the elderly, presenting these symptoms. Patients are categorized as having probable, possible, and unlikely HPN according to their medical history, neurological examination, neuroimaging assessment, and complementary tests. The treatment consists of the interposition of a valve for drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid, because it is an invasive procedure and is liable to severe complications, requiring careful selection of its patients for a better prognosis. From the reported in this case, it is perceived that this is an atypical case of PNHL due to its installation in a previously healthy young patient, who presented with psychotic symptoms and evolved with urinary incontinence and headache. The diagnosis was made through the clinical history and magnetic resonance of the skull. The therapy chosen was the surgical approach with DVP implantation. The patient presented improvement of the symptoms, but with three months postoperative she developed a subdural hematoma that had to be approached surgically twice. Subsequently, the patient had no further complications and was followed up on outpatient follow-up and control with carbamazepine.

The patient in the case reported presented a reality test without compromising and obtained cure of her auditory hallucinations with the treatment of the underlying disease. This fact allowed to conclude that this symptom occurred exclusively in the presence of hydrocephalus and was not related to the diagnosis of psychotic disorder due to PNH. It was, therefore, psychotic symptoms related to a general medical condition. It can also be affirmed that the followup of the case (from initial approach to implemented therapy) was, in general, consistent with what the literature describes. Failure to perform complementary tests, although desirable, did not prevent the success of the treatment and the clinical improvement of the patient.

References

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P (2017) Compendium of Psychiatry: Behavioral Science and Clinical Psychiatry. 11th (edn.). - Porto Alegre: Artmed.

- Hakim S (2012) Some observations on CSF pressure: hydrocephalic syndrome in adults with “normal” CSF pressure [thesis]. Bogota: Javeriana University, School of Medicine; 196 APUD Normal pressure hydrocephalus: current view on the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment (Renan Muralho Pereira1, Laura Mazeti1, Deborah C. Pereira Lopes1, Fernando Campos Gomes Pinto) Arq Bras Neurocir 31(1): 10-21.

- Jucá CEB, Antônio Lins Neto, Ricardo De oliveira, Hélio Rubens Machado (2002) Treatment of ventricular-peritoneal shunt hydrocephalus: analysis of 150 consecutive cases at the Ribeirão Preto Clinic Hospital. Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira 17(3): 59-63.

- Siraj S. (2011) An overview of normal hydrocephalus pressure and its importance: how much we really know. J Am Med Dir Assoc 12 (1): 19-21.

- Oliveira MF, Olivera JR, Rotta JM, Pinto FC (2014) Psychiatric symptoms are found in most patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arq Of Neuropsychiatry 72 (6): 435-438.

- Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P (2005) Diagnosing idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57(3): S4-S16.

- Shprecher D, Schwalb J, Kurlan R (2008) Normal pressure hydrocephalus: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 8 (5): 371-376.

- Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Black PM, Burgsneider M (2005) Diagnosing idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57(3): S4-S16.

- Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Klinge P, Relkin N, Black PM (2005) The value of supplemental ‘prognostic tests for the preoperative assessment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57 (3 Suppl): S17-S28.

- Gallia GL, Rigamonti D, Williams MA (2006). The diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2(7): 375-381.

- Fabiano AJ, Doyle K, Grand W (2010) Delayed stoma failure in adult communicating hydrocephalus after initial successful treatment by endoscopic third ventriculostomy: case report. Neurosurgery 66(6): E1210-1211.

- Pereira RM, Mazeti L, Lopes DCP, Pinto FCG (2012) Normal pressure hydrocephalus: current view on pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Rev Med (Sao Paulo). 91(2): 96-109.

Case Report

Case Report