Abstract

Background: Mass gatherings may strain the planning and response resources of the community hosting the event and create security and public health challenges. We aimed to explore whether a mutual planning and risk assessment tool used by emergency public agencies (EPA=emergency medical services, police officers, and firefighters), and organizers may improve planning and resource utilization before any mass gathering.

Study Design and Methods: Action research based on interdisciplinary group exercises using a validated method “Three Level Collaboration” and real scenarios.

Results: The use of the assessment tool increased the grade of collaboration between public agencies, and organizers and improved the preplanning phase of a mass gathering, particularly for healthcare providers. It was easy to use, feasible for different scenarios and highlighted the significant role and responsibility of organizers in preevent risk assessment.

Conclusion: The new assessment tool (MAGRAT= Mass Gathering Risk Assessment Tool) is an innovative tool for pre-event planning and risk assessment, which may also improve resource management by increasing the multiagency collaboration among public agencies before any major events.

Keywords: Public Agencies; Emergency; Planning; Management; Risk Reduction

Abbreviations: MG: Mass Gatherings, EMS: Emergency Medical Services, PF: Police Forces, FF: Firefighters, EPA: Emergency Public Agencies

Introduction

Mass Gatherings (MG) are defined as occasions, either organized or spontaneous (e.g., sports activities, festivals, and musical events), that attract enough numbers of people every year and contribute to public enjoyment and development of the local and national economy and infrastructure. However, they also strain the planning and response resources of the community hosting the event and create security and public health challenges due to crowding and man-made emergencies and may lead to major incidents or disasters with a high number of casualties [1-8]. Consequently, there is a need for engagement of Emergency Medical Services (EMS), Firefighters (FF), and Police Forces (PF), herein called as Emergency Public Agencies (EPA) [2]. Although many communities rely on their emergency and disaster plans to manage MGs, the evaluation of security and healthcare needs is of inferior quality or nonexistent [7,9,10]. Nevertheless, careful strategies to limit unnecessary delays and guarantee enough resources are needed to meet and prevent the variety of risks associated with MGs [1,10,11].

Although sharing information and integrative planning have proven to be essential factors to improve security and resource assessment [2,7], there has been no collaborative instrument for use before an event. Such a tool may make it easier to define and agree on:

a) The type and potential risks associated with an event,

b) Degree of collaboration,

c) Organizational setting and assembling areas, and finally,

d) To enhance interactive training and discussion [2,7].

A reasonable estimation of risks and needed resources before an event is a prerequisite for creating mutual material and human resources, standard unit leadership, treatment, and triage areas [2,7,12,13]. Earlier Swedish studies have shown that EPA, i.e., PF, FF, and EMS, analyzed and estimated their risks and need for resources, separately [2,14]. Therefore, the concept of a mutual planning and a comprehensive collaboration was evolved through a study [7], in which a Swedish tool for resource estimation at sport events based on the British Purple Guide [15] was created. It was further developed to create STREET (Swedish Template for Risk/ Resource Estimation at EventS) (Appendixes 1&2) for estimation of risks and resources at all events [2,14].

Nevertheless, continuous follow-up and the practical use of the STREET indicated that neither there were enough resources in Sweden to meet the criteria set by the original U.K. guideline, nor were the risk factors affecting Sweden equivalent to that of the U.K. at that time. Furthermore, the results of risk assessment showed profound differences between EPA. While the FF and EMS tended to underestimate and overestimate the risks, respectively, the PFs risk assessment seemed to be more reasonable, realistic, and accurate. Since PF used organizers´ information in its risk assessment, a mutual risk assessment between EPA and organizers seemed reasonable to enhance the possibility of sharing information and improving an individual organization´s resource planning and increase the quality and pace of major incident management [2,14,15-17]. This study aimed to modify STREET template in real events as a planning tool for public agencies and organizers, and to develop a new tool “MAGRAT” (Mass Gathering Risk Assessment Tool). In the first step, beneficiaries, i.e., organizers, and EPA, evaluated STREET in historical real scenarios. The template was modified and adjusted gradually and was finally tested in some major events.

Method

The study was designed as action research in two different stages [18]. The construction of the actions was based on the accumulation of knowledge from action to action, i.e., table-top exercises. Whenever there was a need to take a turn, and focus on specific, not yet examined information in the exercises, a new action was initiated. Notes and fresh ideas or any suggestions were collected and discussed after every act [19]. Further measures focusing on new or different dimensions and items in the template were chosen. Every fulfilled step was also analyzed and discussed. Change of actions was based on the suggestions from research team, and the steering group. A reference group supervised all activities during both stages [20]. In the first stage, we conducted tabletop exercises with three teams of multidisciplinary participants using the three-level collaboration (3LC) model on three different occasions [21]. The templates were improved in content after every single table-top exercise. The results were also discussed with the reference group. The final template was used in actual events using a new routine and procedure, suggested by participants, and approved by the reference group. The collected data were analyzed and presented.

The Template

The original template published for resource estimation at sport event was developed from a broad literature review and was adjusted to a Swedish context in a modified Delphi study to assess the clarity of wording and significance, and to create STREET (Appendixes 1&2). Panels of experts who expressed their views, both quantitatively and qualitatively, evaluated the dimensions and the items relevance to the subject. STREET was developed in order to fit different types of events and to suite various risk factors and figures, which would give an estimation of resources [7]. The template was divided into two parts: risk and resource assessment (STREET one and two) [2,14]. The risk assessment was the responsibility of the EPA together, while resource assessment was done separately before a joint meeting. The result was then adjusted after a final and mutual evaluation of the risks. In this study, we used both parts of the STREET template.

Using the Three-Level Collaboration Model (3lC)

3LC is a training model used to train small or larger groups of participants in various positions in emergencies and major incidents. The collaborative elements in a mutual task are used to reduce the organizational barriers [12,22]. The abilities and limitations in each organization are enlisted to promote an interplay with no hierarchal authority within the own organization and in collaboration with others, as well as the ability to switch between different collaboration strategies based on any specific situation. Collaboration training offers a chance to exhibit stability, to practice transitions, overlaps, fearlessness, improvisation, creative thinking, and the ability to handle unexpected situations in an environment [23], which allows mistakes, correction of errors, and thus, improvement. The designed approach to an event can be tested, and its effects can be evaluated in the next stage to create a new approach, test it again, and develop the method continuously.

Reference Group

The reference group consisted of eight professionals: One female police commander and one firefighter, each with over 20 years of experience commanding and supervising various events; Three male organizers with long experience and responsibility for arranging large-scale events such as concerts and sport events as well as marathon contests; Three male participants from healthcare services of whom one nurse had over ten years of experience in organizing pre-race/MG planning at the regional level, one physician with more than 20 years’ experience in trauma, emergency, and regional disaster medicine planning, and finally, one academic representative with vast experience in clinical care sciences and prehospital work. The latter was also well familiar with the 3LC model.

Working Teams

Three teams were selected and sent to table-top exercises by each organization, respectively. The study group did not know about these selected professionals’ backgrounds. There were 24 professionals with a mean age of 46.2 years, mean experience time of 20.2 years from the following professions: seven policemen, four rescue workers, five healthcare workers, six event-planners (three security professionals, one fire engineer, and two event planners), and two traffic commanders. There were five females and 18 males, and in one case, the information about the gender was missing. These professionals were distributed equally in all teams, which also had at least a representative from each of the major professions, except two traffic planners who participated in two teams. Team A had eight, team B had seven, and team C had nine participants.

Historical Real Scenarios

In contrast to the earlier study in which fictive cases were used, in this study, real scenarios of registered events within sports were used. All groups received the same scenarios. Their comments and suggestions were noted. The Gothenburg half-marathon organized by experienced organizers, with over 40,000 participants, and over 100,000 spectators, was one of the scenarios. The second scenario dealt with a soccer match, in combination with some air show and an organizer with no previous experience. A crowd of over 10,000 visited the arrangement. These scenarios were selected by chance on the first day of the exercises, out of four possible scenarios, and were used in all practices.

Working Procedures

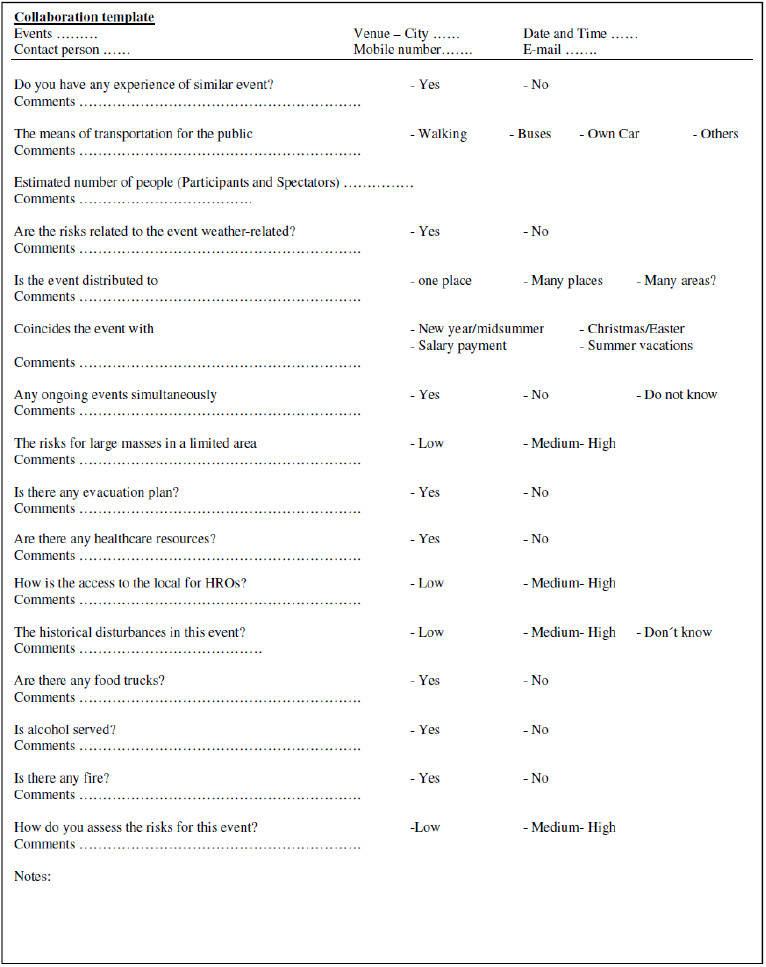

The first session was conducted with participants from team A. The scenarios were discussed within each profession and in the next stage within the whole team. During each discussion, the STREET templates for risks and resource assessment were used. The adjusted and commented versions were discussed before the end of each session, questioning what could have been done better and how the collaboration could be improved. After each session, the newly edited template was presented to the reference group, which evaluated the comments and changed and approved or disapproved the new version. The latest version was then brought into the next team. This procedure was performed for three months, and a new final template (MAGRAT) was developed by adjusting all the questions (Figure 1).

Real Events Utilization

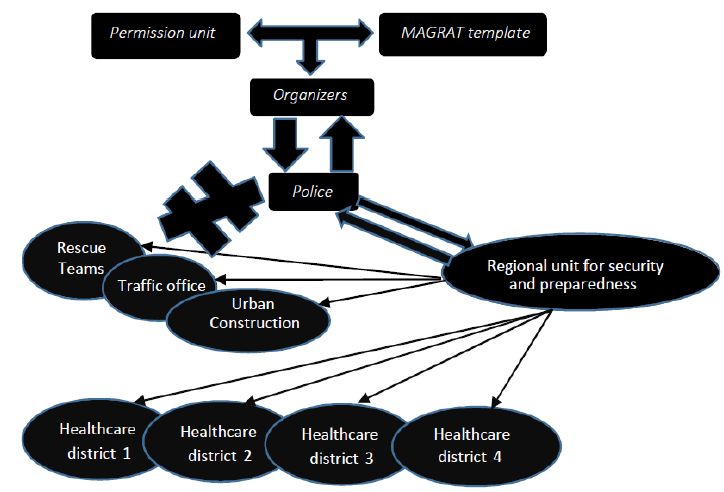

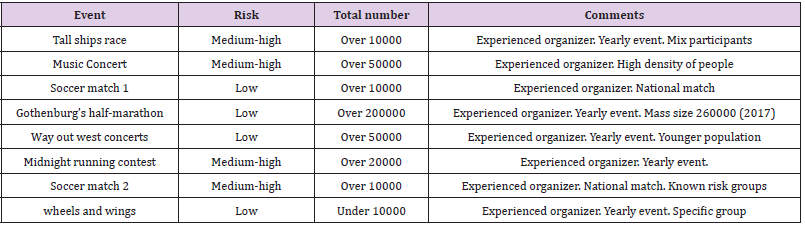

MAGRAT was tested in actual events during the second half of 2017. The teams discussed different strategies and procedures for the utilization of MAGRAT to get the adequate and necessary information from all the organizers. The reference group approved the result (Figure 2). None of the researchers were involved in the selection of the events. The police department, which authorized and selected all event, took the responsibility to send out the template as a digitalized link to the organizers, along with the application forms. However, it was not mandatory for the organizers to fill in and reply. After the completion of MAGRAT, the necessary information was first sent to the regional healthcare group to be completed with additional medical risks/concerns; thereafter, it was distributed by the regional healthcare group to all concerned authorities and affected healthcare districts. If necessary, a dialogue between the organizers and the authorities was initiated. Any necessary change in the template was registered, including the response rate and the analyses of the results.

Figure 2: The process of distributing the new template through the regional healthcare group. In this way the information obtained by the police was completed by the healthcare and distributed to all involved organization. A possible distribution way can be directly from police department, which is shown as ≠.

Results

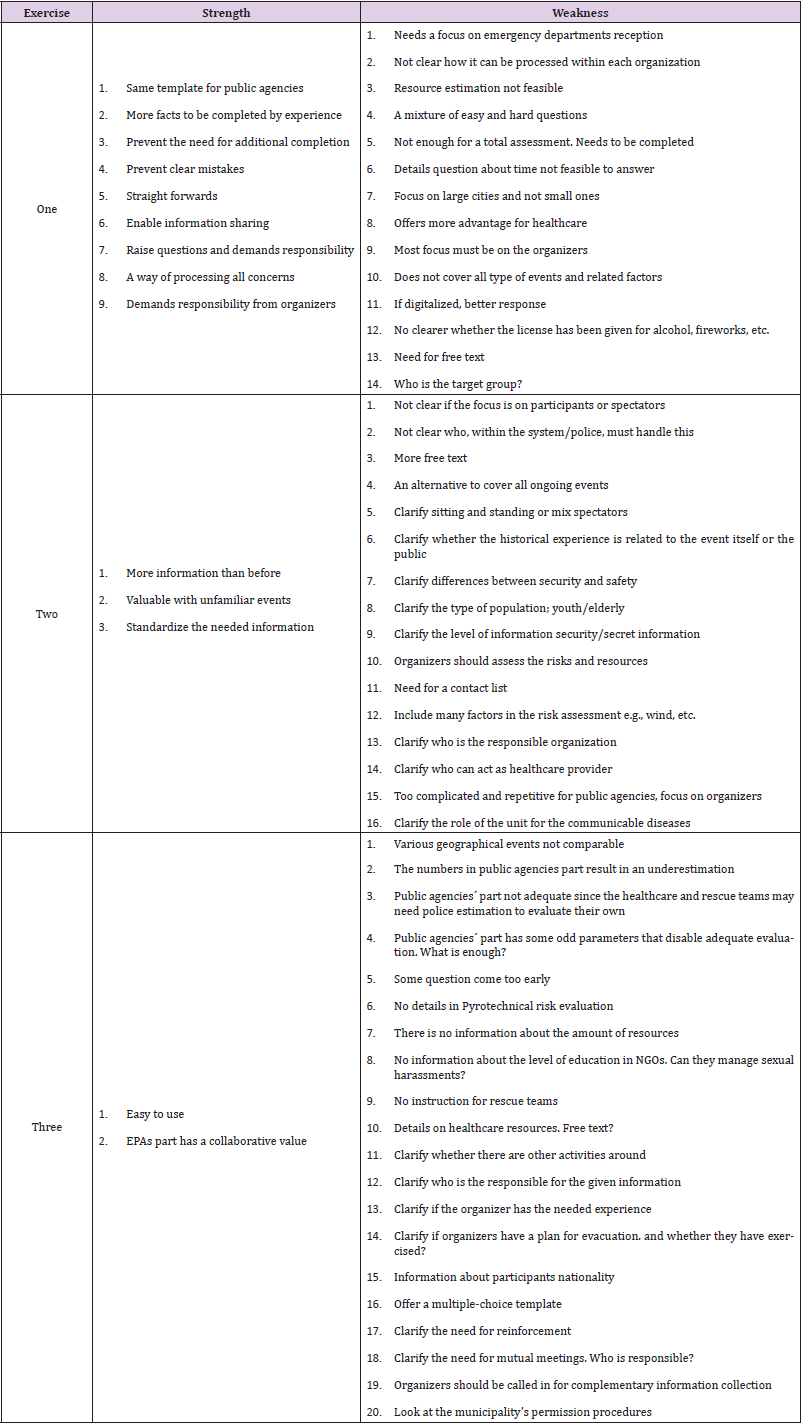

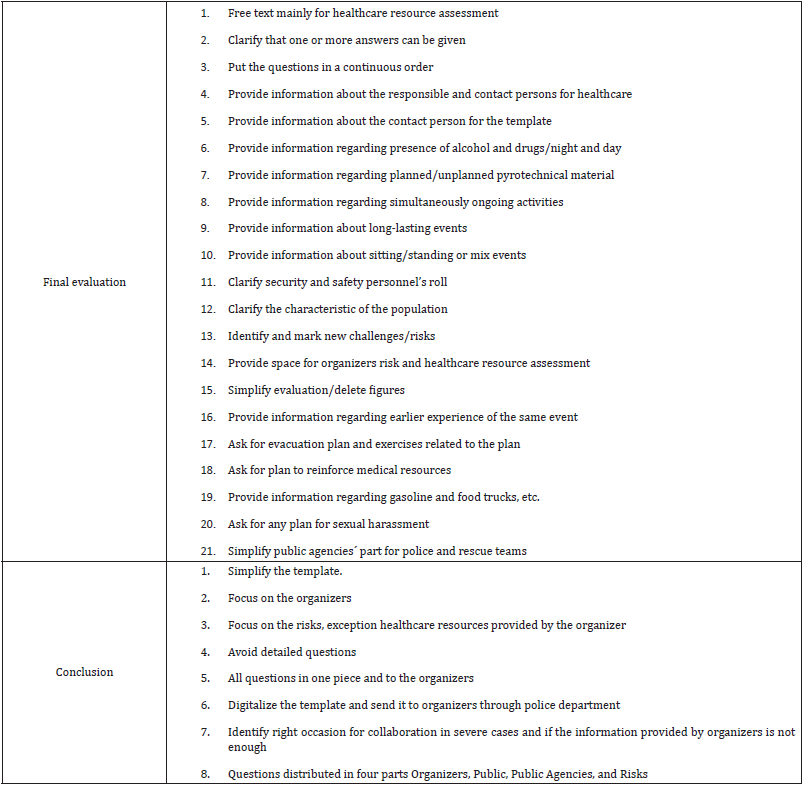

During all three table-top exercises, the teams followed similar procedures by giving the strength and weaknesses of the template and discussing ways to improve it. (Tables 1-3) show these points for each team and during the three sessions of work, as well as how MAGRAT was developed (Figure 1). As seen in Table 1, the number of strengths decreased, while the number of weaknesses increased. Nevertheless, many comments were similar and could be categorized and prioritized depending on the possibility to operate them in the final template. After each exercise, the strengths, weaknesses, and suggestions were discussed in the reference groups. Some of the ideas were accepted, and some were not. In general, comments that might have complicated the process, such as detailed questions, were not accepted. There was an agreement on the following items in (Table 2). Twenty-one points, which should be clarified, provided, simplified, and asked, could be extracted. A conclusion could be drawn, which was the basis for the final template and consisted of a simplification of the template, focusing on organizers and risks rather than resources, and information characteristic for the public. MAGRAT was retrieved from the information in (Tables 1 & 2) and is shown in Figure 2.

It consisted of 16 questions that covered four topics as mentioned above and in Table 2:

a) Organizers: earlier experience, choosing the event during holidays/parallel with another event, and a final risk assessment

b) Public: transport means and number

c) Public agencies: resources mainly for healthcare and access to the event for all, and

d) Risk: weather, space vs. large mass, evacuation plan, history of earlier disturbances, food truck, and alcohol.

Out of 20 organizers in the last stage of this study, only eight completed MAGRAT (Table 3). However, the participating organizers were all representing large events on national and international level, with advanced organizations and many years of experience. MAGRAT was commented upon, and described as:

1) Clear and simple to use and understand

2) Having high relevance to the field,

3) Enhancing the organizers’ preparedness,

4) Enhancing inter-organizational information sharing, and

5) Enhancing the dialogue between the public agencies and organizers. There was no information about the lack of planning nor security shortcomings.

Discussion and Conclusion

The main aims of this study were to further improve the existing collaborative instrument “STREET” in real events and as a planning tool for public agencies and organizers and to establish new routines for its utilization [2,14]. Having presented the results and the procedure, which led to the new tool (MAGRAT), we can see its development from a risk/resource tool to a risk assessment tool and from an all-organizational approach to an organizer´s approach. In both cases, the tool has shown a satisfying feasibility. One important and the common goal during an event is to guarantee the safety of the spectators and the participants and mitigate or prevent public health consequences. From this perspective, risk assessment is a mandatory process by which the impact of any danger can be evaluated, and the risk can be minimized or eliminated. Hence, it then might be possible to estimate the need for resources and a mutual management policy [2-6]. Public agencies, together with organizers, have a responsibility to arrange a safe and entertaining performance. The development of recent events illustrates how events tend to become more spectacular, larger, and complicated. The intensive mass media focus helps some events to become popular nationally or internationally and, consequently, a target for more risks and antagonistic actions [1-3].

Organizers may only recognize their responsibility for events as provider of a social and community-based gathering and leave the management of disturbances to the community financed EPA. However, the increasing numbers of events, and participants, along with economical strain applied to public agencies, have created new challenges and concerns about the accountability and responsibility of EPA [4-5]. Although the initial focus of this study was to evaluate the ability of template to estimate resources and risks, it became apparent that risk estimation might be more standardizable and global than resource assessment. The latter appears to be specific for each organization and depends on other factors such as the size and type of event, and the financial supports [2,14]. Thus, the development of a standard tool went from risk and resource assessment to risk assessment and from focus on EPA to organizers. This approach also changed the content of the template from figures to realistic content, statements, and more free text to be able to absorb the main concerns. The main topics chosen in MAGRAT reflected the end-users needs for more concrete and decisive questions. Experience and knowledge were integrated with a risk assessment to demonstrate competency.

The most important risk factors were chosen as a reminder of the need for planning and expectations. Although this procedure puts the primary responsibility on the organizers to provide adequate and correct information, it is incredibly decisive for EPAs´ preparation before an event and enables a dialogue with the emergency services. The demand for organizers´ ability to have proper planning and performance can not only result in a safer event but also allows them to think twice and try to prevent all pitfalls that can cost money and lives. The results of this study clearly show that partnership is a necessity that can minimize misunderstandings among the public agencies and organizers; furthermore, collaboration can allow making a solid decision based on real facts to organize a safer event. The results also show the willingness of all partners to work together and understand the importance of the procedures. However, there was a low response rate from organizers when MAGRAT was used at real events, and only eight out of 20 organizers responded to our template. Looking closely at the respondents, we realized that they were all largeevent organizers, with advanced organizations and many years of experience.

This probably confirms two facts: first, large events have good planning, based on experience and organizational competency. Secondly, they are more eager to build up a good reputation, and financial resources do not limit the safety of an amusing entertainment. The reason why 60% of the organizers did not reply can be many, but unfortunately, this study does not provide any clear answer. However, we can speculate that many questions in MAGRAT, such as an existing evacuation plan, can be alarming and uncomfortable for small-event organizers. Another reason might be the non-mandatory nature of our template. Even though the template was sent out by the police department, it is yet to be legalized to force all organizers to reply. Since the template proved to be feasible, relevant, easy to use, and enhanced the inter-organizational information sharing and communication, the lack of information concerning any failures may indicate that MAGRAT was a reminder before any event to prevent any shortcomings.

There were some limitations to this study. First, all of those involved in the reference group were selected people with a high interest in mass gatherings. This fact might have had an impact on some of the decisions made in the group, mainly the selection of questions and related factors. Another significant limitation was the low response rate to MAGRAT, which does not give us an appropriate statistical analysis. However, the descriptive analysis of the results may still be indicative of some conclusions. The third limitation is the absence of any legal authority to compel organizers to reply to the template. Even if the template is scrutinized and developed from the literature as well as reviewed by experts, it still has to be improved. The event industry is growing and in constant development; thus, a predictive tool has to follow the progress and uncover emerging risks.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the collaboration between emergency public agencies and organizers before an event is necessary. A template, such as MAGRAT, may facilitate this collaboration by reminding an organizer of unplanned risks/measures before any event. Moreover, EPA and organizers should conduct a mutual risk assessment and share information concerning resource needs and back-up plans, based on the outcome of MAGRAT. The legalization of the template may increase its use.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge following reference group members: Carina Person, Åke Söderberg, Kenneth Lexell, Per Nyqvist, and Jonas Arlmark for their support and guidance throughout the study.

Conflict of Interest:

None.

Funding:

None.

References

- Arbon P (2007) Mass-Gathering medicine: A review of the evidence and future directions for research. Prehosp disaster Med 22(2): 131-135.

- Berner A, Alharbi TS, Carlström E, Khorram-Manesh A (2015) STREET: Swedish tool for risk/resource estimation at events. Part one, risk assessment – face validity and inter-rater reliability. JAD 4(1): 37-43.

- Zeits KM, Schneider DPA, Jarrett D, Zeitz CJ (2002) Mass Gathering events: Retrospective analysis of patient presentations over seven years. Prehosp Disaster Med 17(3): 147-150.

- Donovan C, Bryczkowski C, Mc Coy J, Tichauer M (2017) Organization and operations management at the explosive incident scene. Ann Emerg Med 69(1S): 10-19.

- Paras E, Butler M, Maguire BF, Scarfone R (2017) Emergency preparedness for a mass gathering: the 2015 Papal visit to Philadelphia. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 11(2): 267-276.

- Soomaroo L, Murray V (2012) Disasters at mass gatherings: lessons from history. PLoS Currents 4: RRN1301.

- Khorram-Manesh A, Berner A, Hedelin A, Örtenwall P (2010) Estimation of healthcare resources at sporting events. Prehosp Disaster Med 25(5): 449-455.

- (2019) Communicable disease alert and response for mass gathering. WHO Technical workshop. Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Thackway S, Churches T, Fizzell J, Muscatello D (2009) Should cities hosting mass gatherings invest in public health surveillance and planning? Reflections from a decade of mass gatherings in Sydney, Australia. BMC Public Health 9: 324.

- Arbon P (2004) The development of conceptual models for mass gathering health. Prehosp Disaster Med 19(3): 208-212.

- Zeitz K, Zeitz C, Kadow Griffin C (2005) Injury occurrences at a mass gathering event. Aust J Paramed 3(1).

- Berlin J, Carlström E (2008) The 90 second collaboration: a critical study of collaboration exercises at extensive accident sites. J Conting Crisis Manag 16(4): 177-185.

- Scholtens A (2008) Controlled collaboration in disaster and crisis management in the Netherlands - history and practice of an overestimated and underestimated concept. J Conting Crisis manag 16(4): 195-207.

- Berner A, Alharbi TS, Carlström E, Khorram-Manesh A (2015) STREET: Swedish tool for risk/resource estimation at events. Part two, resource assessment-face validity and inter-rater reliability. JAD 4(2): 112-116.

- (2019) MSB (Swedish Civil Contingency Agency). Event Safety Guide. Stockholm.

- Kapucu N, Tolga A, Demiroz F (2010) Collaborative emergency management and national emergency management network. Disaster Prev Manag 19(4): 452-468.

- Clarcke S (2013) safety leadership: A meta-analytic review of transformational and transactional leadership styles as antecedents of safety behaviors. J Occup Organ Psychol 86(1): 22-49.

- Whyte WF (1991) Participatory Action Research, Action Research. Sage Focus Editions.

- Tillyer R, Tillyer MS, Mc Cluskey J, Cancino J (2014) Researcher practitioner partnerships and crime analysis: a case study in action research. Police Practice and Research 5(5): 404-418.

- Mc Niff J (2013) Action research: Principles and practice. Routledge.

- Khorram-Manesh A, Berlin J, Carlström E (2016) Two validated ways of improving the ability of decision-making in emergencies; results from a literature review. Bull Emerg Trauma 4(4): 186-196.

- Berlin J, Carlström E (2010) From artefact to effect: the organizing effects of artefact on teams. J Health Organ Manag 24(4): 417-427.

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM (2015) Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, USA.

Research Article

Research Article