Abstract

Because there has been a lot of speculation regarding the origins of the new coronavirus causing the 2020 pandemic, that lead to many deaths, social distancing and economic drawback, we wanted to investigate the route of transmission of this virus and whether its genome may contain elements taken from other viruses. For this purpose, we used the National Center for Biotechnology Information data base and we were able to compare SARS-COV-2 to other coronaviruses, as well as other RNA viruses from different families. We found that the bat-pangolin-human route of transmission may not be very accurate. And after comparing almost all the canine coronaviruses from the NCBI database and finding no significant similarities between their genomes, we found canine coronavirus, strain CB/05, that showed a percentage of 75,66%. We concluded that the route of transmission is still opened for debate and domestic animals should be included in this investigation.

Short Communication

SARS-COV-2 was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 Gorbalenya, et al. [1] and as reported in another recent study it had killed more than 350,000 people worldwide by the end of May 2020 Martellucci, et al. [2], a significant number, which according to the World Health Organization (WHO) data has recently reached 863,020 (WHO, 2020)[3]. A very interesting paper written by Prof. Eskild Petersen et al, revealed that although SARS-COV-2 is not as deadly as SARS-COV and MERS-COV it is much more contagious and the morbidity and mortality caused by this virus were much higher than an influenza pandemic Petersen, et al. [4]. The virus seems to be very hard to control, as diagnosing SARS-COV-2 infected people is difficult, rapid detection methods based on specific antibodies presence can sometimes offer false positive or false negative reactions and the high mutation rate of the virus makes it hard to give a reliable diagnosis even by molecular methods. Even the symptoms of the people infected with this virus can vary significantly, among them: fever (99%), chills, dry cough (59%), sputum production (27%), fatigue (70%), lethargy, arthralgias, myalgias (35%), headache, dyspnea (31%), nausea, vomiting, anorexia (40%), and diarrhea Valencia [5]. There has been a lot of controversy in regards of the emergence of the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, some authors even suggested this is a laboratory made virus, that carries elements from other human pathogens, making it very dangerous and difficult to control. The currently accepted theory of its transmission to humans is that SARS-COV-2 originates from bats and that the transmission to humans was mediated by palm civets in Guangdong Province, China Sharma, et al. [6]. But not long ago there was talk about the pangolins been the source of transmission to humans, has suggested by Li, et al. [7] This theory is now been questioned by Ping Liu and his team in a recent article Liu, et al. [8].

Genome Comparison of SARS-COV-2 and Other RNA Viruses

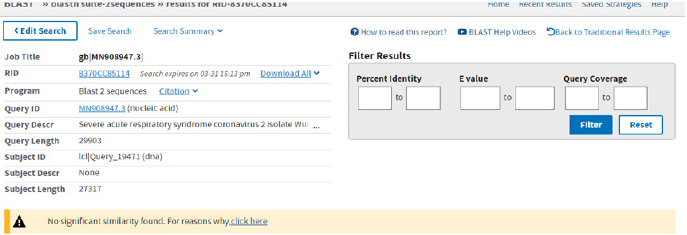

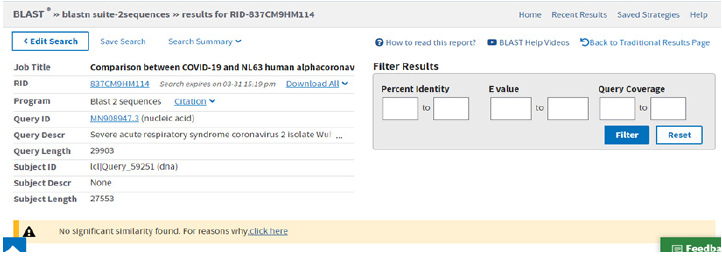

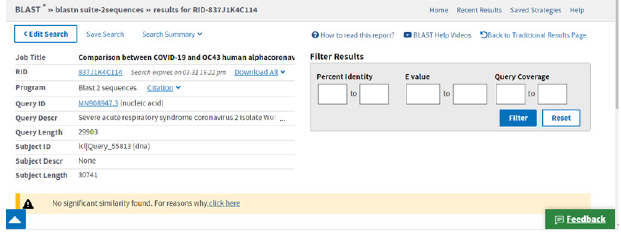

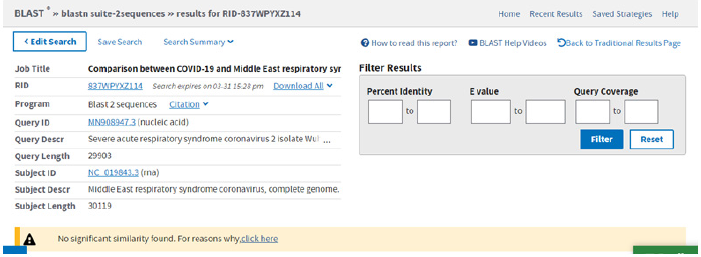

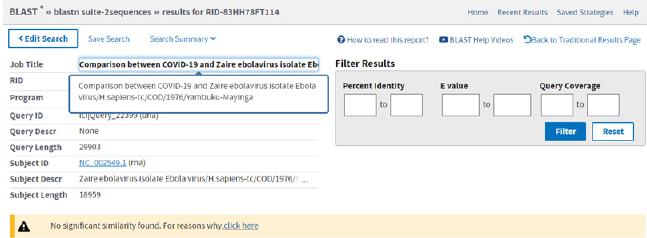

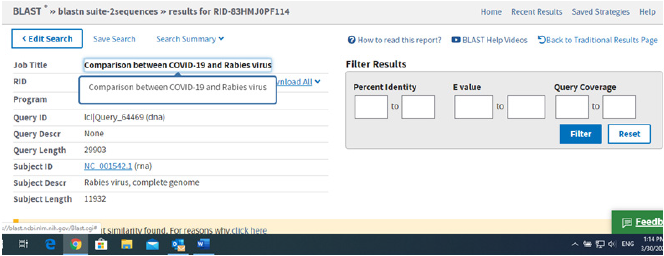

Thus, taking these ideas step by step we decided to investigate the SARS-COV-2 genome and some specific proteins in order to determine if notable similarities can be found between this virus and other animal specific Coronaviruses and also viruses such as: human Alphacoronavirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS), Hepatitis C virus genotype 1, Ebola virus, Rabies virus and Severe acute respiratory syndrome virus (SARS). All the searches in the NCBI (National Center for Coronaviruse Information) database were carried out by selecting only highly similar sequences, so there is no misunderstanding. None of the viruses belonging to other families had shown any significant similarities to SARS-COV-2, as it can be seen from the results in Figures 1-6.

Figure 5: Comparison of SARS-COV-2 genome and Zaire ebolavirus isolate Ebola virus/H.sapiens-tc/COD/1976/Yambuku- Mayinga.

Similarities Between SARS-COV-2 and Animal Coronaviruses

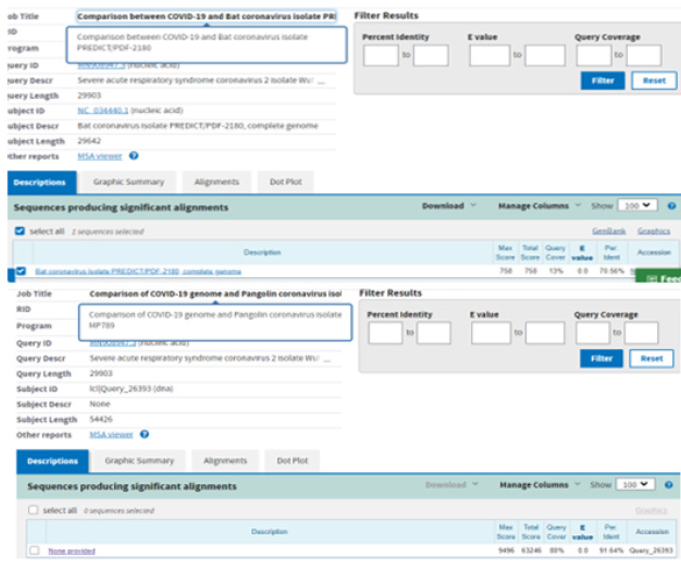

Then we started looking at animal specific coronaviruses and of course we first evaluated the homology between bat and pangolin coronaviruses and the human one and both showed highly similar sequences, with percentages such as 70,56% for the bat isolate and 91,64% for the pangolin isolate (Figure 7). Then, we thought it would be interesting to see the highly similar sequences of the two animal coronaviruses, so we compared the bat genome with the pangolin one. We obtained a similarity of 85,47%, with a query cover of 99%. However, the percentage is not very high, because for instance when we compared the SARS-COV-2 genome and the SARS genome, we obtained a homology of 78,38% and these are considered to be different viruses. It could be that the virus either was contracted by the pangolin through an intermediary host or after jumping from the bat to the pangolin it undergone mutation with a very high rate, possibly over a large period of time. Which raises another question, how come people did not get infected long ago, because eating pangolin meat has been a tradition in China for a very long time. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which regulates the international wildlife trade, has placed restrictions on the pangolin market since 1975 and in 2016 this animal was added to the highly endangered species Carrington [9].

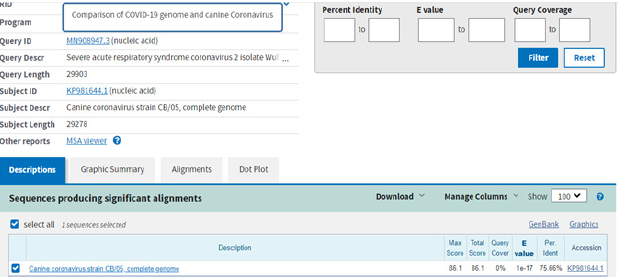

After evaluating the hypothesis that bats and pangolins may be the source of the new and very dangerous human coronavirus, we thought we should take a look at other animal coronaviruses, to see if maybe we could find another intermediary host. Because it rarely happens, but our pets (cats and dogs especially) can sometimes be the source of different human infections (yeast infection, rabies, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), toxoplasmosis, etc.) we thought we should check the homology of some cat and dog specific coronaviruses. After performing diligent searches, we found a canine coronavirus, strain CB/05, that showed a percentage of 75,66% (Figure 8). At the first look it may not appear to be much, but we have compared almost all the canine coronavirus strains genomes available in the NCBI database (Coronavirus Canine coronavirus strain A76, canine Coronavirus Canine coronavirus strain CCoV/NTU336/F/2008, Canine coronavirus strain HLJ-073, Canine coronavirus strain HLJ-072, Canine coronavirus strain HLJ- 071, Canine coronavirus strain S378, Canine coronavirus strain K378, Canine coronavirus strain 171, Canine coronavirus strain TN-449, Canine coronavirus strain 1-71, etc.) and none of them had any highly similar sequnces except the CB/05 strain. This means we should further investigate the possible implication of domestic animals in the extremely fast dissemination of SARS-COV-2. A recent study (August, 2020) has already reported evidence of human-domestic animal transmission. Minks from 27 farms in the Netherlands were infected with SARS-COV-2 from symptomatic people working there, the hypothesis was confirmed when one hospitalized person tested positive for SARS-COV-2 Hosie, et al [10,11]. So, in light of these findings, could it be possible that the virus can be transmitted both ways, from humans to domestic/farm animals and from animals to humans?

Spike Protein Sequence Comparison Between SARSCOV- 2 and Other Coronaviruses with High Genome Homology

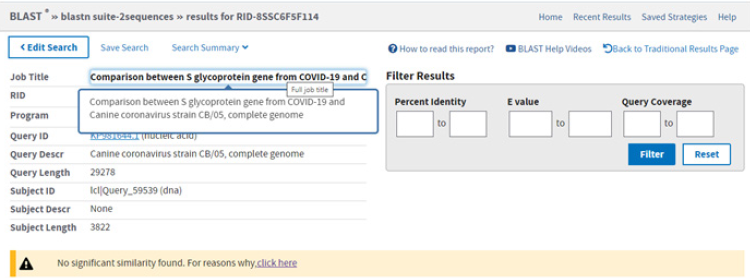

Our study revealed that SARS and SARS-COV-2 spike proteins sequences have a similarity of 78,38%, pangolin spike protein had 89.77% homology and when we compared it to the canine virus strain CB/05 no significant similarities were found (Figure 9). This suggests a very high mutation rate in the sequence encoding protein S, which is expected, as this surface protein is a target for the immune system and the virus needs to successfully avoid been annihilated by the immune system.

Conclusion

It appears that the bat-pangolin-human transmission route is not quite certain, and the exact route of transmission is to be determined. The fact that highly similar sequences were found in a canine coronavirus suggests we should further investigate the possibility of SARS-COV-2 transmission to humans via domestic animals. The spike protein encoding sequence seems to suffer a high mutation rate among both human and animal coronaviruses and this means that the development of highly efficient diagnosis methods and vaccines based on this antigen may encounter some drawbacks.

Acknowledgment

The study was financed by UEFISCDI Project Code: PN-IIIP2- 2.1-SOL-2020-0061 ctr 15Sol/2020 and co-financing by DDS Diagnostic SRL.

References

- Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, de Groot RJ, Drosten C, et al. (2020) The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nature Microbiology Nat Microbiol 5: 536-544.

- Martelluccia AC, Flaccob EM, Cappadonab R, Bravic F, Mantovanid L, et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: An overview. Advances in Biological Regulation 77.

- (2020) World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Numbers at a glance.

- Petersen E, Koopmans M, Go U, Hamer HD, Petrosillo N, et al. (2020) Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics.

- Valencia ND (2020) Brief Review on COVID-19: The 2020 Pandemic Caused by SARS-CoV-2. Cureus 12(3): e7386.

- Sharma A, Tiwari S, Deb KM, Marty LJ (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): a global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int J Antimicrob Agents 56(2): 106054.

- Li X, EE Marichannegowda HM, Foley B, Xiao C, et al. (2020) Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection. Sci Adv 6: eabb9153.

- Liu P, Jiang ZJ, Wan XF, Hua Y, Li L, et al. (2020) Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)?. PLOS Pathogens.

- Carrington Damian (2016) Pangolins thrown a lifeline at global wildlife summit with total trade ban. The Guardian.

- Hosie JM, Hartmann K, Hofmann Lehmann R, Addie DD, Truyen U, et al. SARS-Coronavirus (CoV)-2 and cats.

- Oreshkova N, Molenaar JR, Vreman S, Harders F, Munnink OBB, et al. (2020) SARS-CoV2 infection in farmed mink, Netherlands. Euro Surveill 25: 23.

Short Communication

Short Communication