Abstract

Metformin Associated Lactic Acidosis (MALA) in the setting of impaired renal function may result in severe acidosis with an array of detrimental consequences on human physiology. The often-quoted mortality rate of MALA hovers around 50% although improving recognition may soon affect this statistic. We present a case of what we believe to be the lowest reported arterial pH in a patient who survived. This case demonstrates many of the adverse consequences believed to be attributable to severe acidosis in addition to demonstrating acidosis survivability at levels previously believed to be universally fatal. We exhibit the case of a 61-year-old African American female who presented with hypothermia, altered mental status, and an arterial pH of 6.25, believed to be secondary to Metformin Associated Lactic Acidosis. During admission she suffered cardiac arrest, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and a prolonged state of unresponsiveness, but ultimately recovered to the extent she was discharged home. The clinical significance of severe acidosis has been poorly studied in humans despite its common appearance in critically ill patient populations. Ongoing research on pathophysiology and treatment of severe acidosis is needed.

Keywords: Metformin; Acidosis; Arterial pH; Hypothermia; Cardiac arrest

Abbreviations: MALA: Metformin Associated Lactic Acidosis; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Introduction

Severe acidosis has significant adverse consequences on many aspects of human physiology. Most texts would argue that an arterial pH of less than 6.8 is not compatible with life, yet there are numerous case reports of human survival when the arterial pH is significantly lower, particularly in patients with lactic acidosis that is not driven exclusively by hypoxia. We present a case of lowest reported pH in a patient with severe type-B lactic acidosis and hypothermia who survived to hospital discharge.

Case Presentation

A 61 year-old female was brought to the ED by her husband with a chief complaint of headache, dyspnea, and blurry vision. She had a past medical history significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, nephrolithiasis, major depression, cholecystectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. She was a non-smoker and did not consume alcohol or other illicit drugs. Her outpatient medications were metformin, losartan, metoprolol, hydrochlorothiazide, glyburide, simvastatin, fluticasone nasal spray, as-needed nitroglycerine spray which she did not use, amitriptyline, and conjugated estrogens. She also had a history of penicillin, sulfa, aspirin, and tetracycline allergies. On arrival to the emergency department, the patient was somnolent and confused and her initial finger-stick-blood-glucose was 30 mg/ dL. 50% dextrose was immediately given which increased her blood glucose to 390 mg/dL, but without improvement in mental status.

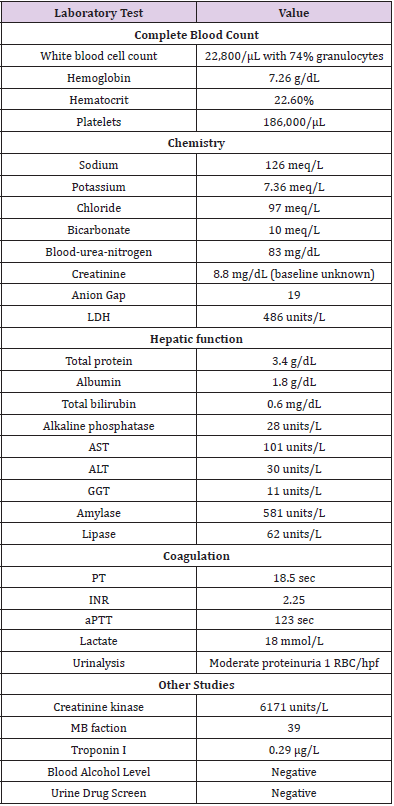

Physical exam revealed an obese African American female in acute respiratory distress, with rapidly increasing confusion and somnolence. Rectal temperature was at 88oF, heart rate was 75/ min, blood pressure was 94/48, and a respiratory rate was 35/ min. Her oxygen saturation was in the 80%’s on room air and 93% on 100% non-re-breather facemask. Her Glasgow coma scale was 10 (eyes 4, speech 2, and motor 5). Her pupillary exam revealed a non-reactive right pupil that was approximately 8 mm and a left pupil that was normally reactive to light and approximately 5 mm. Her oropharynx was moist and pink. Pulmonary exam revealed bilateral rales. Cardiovascular exam was grossly unremarkable, including normal distal pulses, and the absence of jugular venous distention. Her abdomen was protuberant but soft and without apparent tenderness. Rectal exam showed decreased tone and soft brown stool. Her skin was cool to the touch but without rash. The remainder of her neurologic exam was non-focal. Chest radiography was unremarkable. ECG showed sinus rhythm with peaked T-waves, but otherwise normal conduction. Laboratory evaluation was notable for an arterial blood gas showing pH 6.25, PaCO2 19 mm Hg, PaO2222 mm Hg. Three subsequent measurements were nearly identical on two separate blood gas analyzers. Additional laboratory results are shown in Table 1.

She was intubated in the ED and transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). During intubation she aspirated gastric contents. Her problem list on admission included: multi-organ system failure, possible metformin associated lactic acidosis vs. ischemic muscle or bowel, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, and possible sepsis.

In the ICU, emergent hemodialysis was initiated using a high bicarbonate dialysate to correct her acidosis, presumed metformin accumulation, and multiple electrolyte derangements. Her electrolytes were rapidly corrected to normal ranges, her pH corrected to 7.1, and her elevated lactate declined to normal levels. Glycemic control was achieved with an insulin drip, she received warm intravenous fluids and warm dialysate, and was transfused one unit of pack red blood cells and six units of fresh frozen plasma. A diagnostic peritoneal lavage returned clear fluid. A nasogastric tube returned coffee ground material and black fluid. Abdominal radiography demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel but no evidence of perforation.

She developed cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity. Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved following two minutes of advanced cardiac life support. She subsequently required blood pressure support with vasopressors and remained on them for the first four days of hospitalization. Due to the patient’s unresponsiveness and concern for possible bowel catastrophe, on hospital day 2, she underwent a negative exploratory laparotomy. The wound was left open until hospital day eight. The patient developed severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) on hospital day two (P:F ratio of 50). She was subsequently paralyzed, placed in the prone position, and transitioned to high frequency oscillatory ventilation. Aggressive intravascular volume reduction was achieved using hemodialysis. These interventions led to improved gas exchange and she was returned to pressurecontrolled ventilator settings on hospital day six. Despite clinical hemodynamic and metabolic improvements and discontinuation of sedation and paralysis she remained unresponsive. Computerized Tomography of her head was negative. Cultures throughout the patient’s hospitalization remained negative and her serum creatinine declined to 1.7 at the time of transfer to the floor.

Over the next two weeks, the patient experienced gradual return of responsiveness and orientation. She was extubated successfully on hospital day 19 and transferred to the ward on day 21. There, the patient recovered steadily and was ultimately discharged home in stable condition.

Discussion

This case reports the lowest recorded pH with subsequent patient survival to functional recovery in the medical literature. Several instances of survival following arterial pH values <6.8 have been documented in the literature [1-3]. These include two cases of near drowning with hypothermia and acidosis in a 37 and 24 year old man who survived despite cardiorespiratory arrest and an uncorrected arterial pH of 6.33, and two occasions of metforminassociated lactic acidosis in elderly patients: one involving a patient with an arterial pH of 6.5 and another in a patient with a pH of 6.38. The differential diagnosis of life threatening metabolic acidosis is relatively narrow including overwhelming infection, shock of various etiologies, ischemic bowel or other soft tissue necrosis, carbon monoxide or cyanide poisoning, severe anemia, diabetes mellitus, cancer, liver disease, pheochromocytoma, medication effect, toxic ingestion or exposure, and thiamine deficiency [4]. Lactic acidosis has been defined in current clinical practice by a pH less than or equal to 7.35, lactatemia greater than 2.0mmol.l-1, with PaCO2 less than or equal to 42 mm Hg [5]. While it is difficult to conclusively determine the etiology of the patient’s severe lactic acidosis, her response to hemodialysis without subsequent evidence of malignancy, overwhelming infection, or bowel catastrophe suggests metformin induced lactic acidosis (MALA) as the etiology of this patient’s severe metabolic derangements. It is possible that gradual deterioration in renal function may have led to drug accumulation in our patient, rather than intentional excess exposure. Metformin is believed to increase the risk of elevated lactate by a proposed mechanism that includes the inhibition of gluconeogenesis and mitochondrial impairment. MALA prevalence is reported to be around 5 cases per 100,000 patients [6]. Acidosis is a frequent complication for critically-ill patients and may be either the primary problem, or secondary to a variety of other common chronic conditions. At this time, metformin remains contraindicated in patients with chronic medical conditions that may increase the risk of tissue hypoxia and development of lactic acidosis such as cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, and liver disease. Additionally, clinical history or suspicion of large-dose metformin ingestion or deteriorating renal function continue to be recognized as risk factors for the development of MALA. The pathologic mechanism of MALA remains widely disputed and in fact, several systematic reviews and meta-analyzes have proposed no increased risk of lactic acidosis with metformin treatment compared to placebo and other nonbiguanide diabetic therapies [7]. As supported by a multitude of case studies of patients with an extremely low arterial pH [8,9], we observe that despite the high mortality of MALA, and given the same profound level of acidosis, prognosis of MALA is significantly better than that of lactic acidosis of other etiology.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Army Medical Department, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

References

- Opdahl H (1997) Survival put to the acid test: extreme arterial blood acidosis (pH 6.33) After near drowing. Critical Care Medicine 25(8): 1431-1436.

- Watson J, Mora A (2016) An Extreme Case of Metformin-Associated Lactic Acidosis with a Remarkable Outcome. CHEST Journal 150(4_S): 441A-441A.

- Ahmad S, Beckett M (2002) Recovery from ph 6.38: lactic acidosis complicated by hypothermia. Emerg Med J 19(2):169-171.

- Kraut Jeffrey A, Nicolaos E Madias (2014) Lactic acidosis. New England Journal of Medicine 371(24): 2309-2319.

- Kimmoun A, Novy E, Auchet T, Ducrocq N, Levy B (2015) Hemodynamic consequences of severe lactic acidosis in shock states: from bench to bedside. Critical Care 19(1): 175.

- Andersen L W, Mackenhauer J, Roberts J C, Berg K M, Cocchi M N, et al. (2013) Etiology and therapeutic approach to elevated lactate. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 88(10): 1127-1140.

- Salpeter S R, Greyber E, Pasternak G A, Salpeter E E (2003) Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta- analysis. Archives of internal medicine 163(21): 2594-2602.

- Friesecke S, Abel P, Roser M, Felix S B, Runge S (2010) Outcome of severe lactic acidosis associated with metformin accumulation. Critical Care 14(6): R266.

- Lalau JD, Race JM (2000) Metformin and lactic acidosis in diabetic humans. Diabetes Obes Metab 2(3): 131-137.

Case Report

Case Report