Abstract

Background: Tracheal intubation carries an elevated risk of exposure to SARSCoV- 2 due to the generation of aerosols containing high concentrations of the virus. An airway box was designed to mitigate exposure of healthcare professionals performing intubations.

Aim: We evaluated usability of the airway box as a protective device during high-risk airway procedures.

Materials and Methods: After IRB approval. Clinicians were educated on using the device through simulation, intranet learning modules, and emailed resources. The airway box was made available in the emergency department, critical care units, perioperative area, and operating rooms. QR codes affixed to the box, emailed, and displayed in common areas provided easy access to complete a Redcap survey eliciting providers’ experience. Data was collected and analyzed between April 1 and July 31, 2020 on Redcap and results were analyzed.

Results: 687 emergent intubations occurred. 232 were performed by anesthesiologists, 315 by emergency department providers, and the remainder by critical care specialists. 39 surveys were completed, 29 from intubations in the operating room, 3 from the critical care units, 5 from interventional radiology suites, and 2 perioperatively. Providers found the device to be readily available, with a score of 4.51/5, and majority of providers, 60%, found the device easy to use rating it either a 4 or 5 out of 5. Providers acquired mean mallampati score of 1.75, and 1.40 mean laryngoscopic grade view.

Conclusion: Intubation boxes may effectively mitigate high-risk viral exposure during airway procedures. Survey responses show that devices were easy to use and did not significantly affect visualization of the airway. Similar to mask use, enclosure devices in clinical practice should become a vital part of the fight against the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Keywords: Intubation; Personal Protective Equipment; Safety

Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARSCoV- 2) has led to over 73 million total cases and more than 1.6 million total deaths in the world and about 17 million cases in the United States and more than 300, 000 deaths in the United States. Studies have that found tracheal intubation has an increased risk of exposure to certain pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 [1,2]. It has changed our daily routines and healthcare practices.

An Airway box was designed to help decrease exposure as it is a physical barrier between the provider and patient to decrease risk of a direct spray of aerosolized viral particles during the manipulation of the airway. The study showed that without any barrier implementation the particles spread to a 2-meter radius. With the device the particles were contained within the device [3]. Healthcare providers are essential in the fight against SARSCoV-2 and protecting clinicians is a priority. Large scale personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages have created the necessity to conserve resources while limiting exposures that spread SARSCoV- 2. Some procedures confer a higher risk of viral aerosolization and exposure therefore making them high priority intervention targets to limit the spread. Intubation and extubation of the airway are examples of high-risk procedures that endangers the provider due to potential direct aerosolization of viral particles to the providers face. This direct spray of aerosolized droplet particles larger than 5μm present a plausibly significant exposure risk for SARS-CoV-2 [4]. Up to 8% of SARS-CoV-2 cases require intubation and data from the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that 80% of SARS-CoV-2 infections are asymptomatic or present mild symptoms [5]. When SARS-CoV-2 patients and asymptomatic carriers require intubations, it creates a substantial risk to the provider.

Many facilities require a SARS-CoV-2 test for patients prior to entering the hospital for scheduled procedures. Even with testing, there is a risk of intubating patients with undetected infections. An article in the New England Journal of Medicine found SARSCoV2 tests have a 2- 29% false-negative rate [6]. If the intubation box is utilized during all intubation/extubation events, it could significantly limit the undetected exposure when a provider perceives no risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure from patient. The device’s merit relies on the effective low-cost reusable nature to its potential addition to SARS- CoV-2 PPE. The vast impact of the pandemic necessitates evaluation of all options to decrease spread and protect clinicians. The Association of Anesthetists discusses the need for modifications to reduce nosocomial infections citing that more than 20% of SARS-CoV-2 infections are healthcare workers [7]. Utilizing the airway box in clinical practice may decrease risk of transmission. In theory, ensuring total paralysis during intubation should prevent aerosol formation from respiration, gagging, and coughing but comes with its own risks. Another high-risk situation is extubation, where paralysis is not an option and coughing is common. There is limited information about the amount of aerosolization that occurs during extubation. Simply positioning the airway box over the patients head before intubation, extubation and during airway manipulation could mitigate transmission risk.

We aimed to evaluate the perceived efficacy, utility, and potential implications of large-scale implementation of the intubation box as a functional piece of PPE against COVID. Our assumption is that the low-cost, easy-to-use device decreases potential exposure through the physical barrier separating the provider and patients. Our tertiary care academic center collaborated with the institution’s College of Engineering to design, produce, and implement an intubation protection device [8]. Our goal in this study is to acquire feedback from providers using intubation boxes as an addition to PPE protecting healthcare providers performing high risk procedures during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The priority of this study was to acquire input from the highly trained specialists on device feasibility. Specifically, the ease of use, procedural safety, and grade of intubation View. This would provide valuable insight into clinicians’ viewpoint and help indicate the likelihood of success with implementation.

Materials

After the School of Engineering produced the boxes, they were distributed to the operating rooms, intensive care units, emergency department, and floor units. The 4 sided 20-by-20-by- 20-inch barrier enclosure device incorporated 2 side holes 6.5inch in radius for patient access. The clear plexiglass box is placed over the patient’s head during the procedure, the provider gains access to the airway using the holes in the box and performs the intubation. The box was used in conjunction with plastic drapes placed on the patient contiguous to the box. In conjunction with a whole-body plastic drape, the box is designed to physically block aerosolized particles from spraying into the provider’s face during the procedure.

Methods

After IRB approval, a red cap survey (Survey Questionnaire on redcap). was set up to assess interest and feedback on intubation boxes. Clinicians were made aware of intubation box availability and were invited to practice intubations in the COVID Intubation Simulation room that was created in our institution. Clinicians also received education via email and intranet learning modules about methods to intubate, extubate, cleaning and storage of the intubation box. Nurse educators, respiratory therapists and clinicians were all educated about the airway box and were also informed about the study. Following education of providers, the airway box was made available in the emergency rooms, critical care units, perioperative area, and operating rooms. All staff were encouraged to use it for intubation, extubation, and procedures that manipulated the airway. A QR code to fill out the survey was adhered to the box, emailed to all staff, and posted in common areas. We closed the survey July 31, 2020 and analyzed the results from redcap. The information was collected using a Likert scale for the questions that assess the opinion of the device. Other pertinent informational data was collected from listed options. Standard statistical analysis of the data was conducted to determine mean, median, standard deviation and variance.

Results

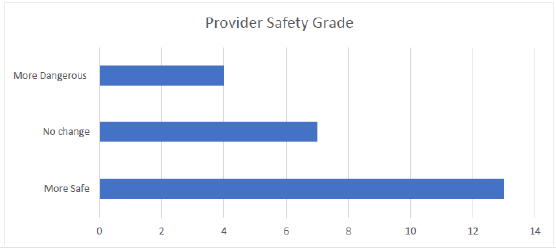

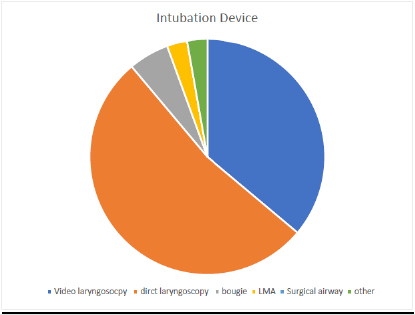

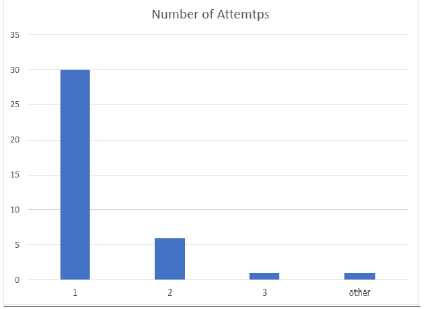

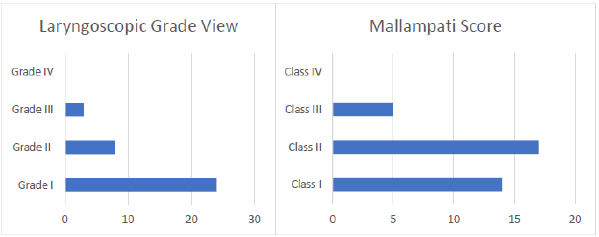

Between April 1 and July 31, 2020, 687 emergent intubations occurred. Of which, 232 were performed by Anesthesiologists, 315 in the emergency department and the remainder were performed by critical care specialists. During the same period, 39 surveys were completed. Since this is a survey eliciting provider feedback on the intubation box itself, there was no need to review patient charts. The surveys were reported from the following clinical areas: 29 were performed in the Operating room, 3 in the critical care units, 5 in interventional radiology suites, and 2 in the perioperative setting (Figure 1). Providers found the device to be readily available, with a score of 4.51/5, and a majority of providers, 60%, found the device easy to use, rating it either a 4 or 5 out of 5. However, the device was only utilized 2 times on a patient that was noted to have a difficult airway. Providers acquired mean mallampati score of 1.75, and 1.40 mean laryngoscopic grade view. The device was utilized primarily in the OR accounting for 76% of surveys submitted. The box was used for intubation 82% of experimental entries. The device availability showed a mean rating of 4.51/5, 86% of providers rated the device as a 4 or 5 on a 1 to 5 scale. The devices ease of use was graded 3.51/5 on a 1-5 scale, 60% of providers graded the device a 4 or 5 and only 14% grading device with a 1/5. Average number of attempts is 1.29 with 78.9% successful intubations on the first attempt. The mean mallampati score of 1.75(14 class I, 17 class II, and 5 class III scores) and the mean laryngoscopy grade view was 1.40 (24 Grade I, 8 grades II, and 3 grade II views) with 68% achieving a grade I view.

In 94% of data entries, provider deemed that the patient did not have a difficult airway and the average BMI of patients was 29.42 with a maximum BMI of 45. Adjuvant protective methods were used in 36 of 39 attempts including clear plastic drape, clear plastic drape with arm slits, and other. The devices used to perform showed that as expected either video or direct laryngoscope was selected in 88.89% of attempts. The average procedure time, from medication administration to intubation, was 3.26 minutes with a maximum time required of 11 minutes and a minimum of 1 minute required. (Figures 1-5) illustrate the data.

Figure 4: Number of attempts required by the provider with Airway Box during procedure (intubation/ extubation).

Figure 5: Laryngoscope grade view and Mallampati score achieved with Airway Box during procedure (intubation/ extubation).

Discussion

The airway box is an emerging solution for mitigating risks of performing airway procedures during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Due to the rapidly evolving research, the intubation box has faced minimal clinical evaluation to ascertain whether the device can be effectively utilized by frontline workers. It is not only important to research the efficacy of the protection created by the device, but it is imperative to determine the impact on the provider’s ability to position the patient, obtain an adequate view of the glottis, and safely place (or remove) an airway in a timely fashion. Our study aimed to evaluate the utility of the device, identify limitations of the box and to determine if there is a path to incorporation the box into routine use for airway procedures. This study indicates that the device was easy to use, readily available, and overall had a perceived safety benefit. However, it was still only used 38 total times during a period that saw 687 emergent intubations. Despite the benefits indicated in the survey, providers’ apparent lack of interest was a significant limiting factor and could indicate future difficulty in expansion to PPE protocol. Stronger research on safety benefits would help education and commitment. Providers achieved an average Mallampti score of 1.75 and average glottic view of 1.4 using the box with 78% being successful on first attempt. This data paired with the direct survey question regarding ease of use (3.51/5) suggest that providers did not find significant difficulty in performing procedures with the device.

However, the box was only used on a difficult airway twice and the mean BMI of study participants was 29.42. This study does not indicate that this device increases the difficulty of the procedure, but the data warrants further investigation as to why the device was not used for more difficult airways. A study designed to incorporate more difficult airways could be implemented once it is determined if the potential decreased exposure risk warrants large-scale implementation. In a controlled setting, this would help identify possible unforeseen limitations created by the device. The study’s subjective approach designed to ascertain the opinions from providers was an important step in the progression of the device but also limits the external validity of the study. The study does not attempt to evaluate particle concentrations, and specific quantitative protective benefits. The box has been suggested to increase the time required to perform the intubation. In our study, the mean time required to successfully intubate the patient was 3.26 minutes. One a study found that without the airway box no intubation took longer than 1 minute, but in our study 58% took over 1 min and 17% took over 2 minutes [9]. Any increased time required to perform the procedure directly leads to increased risk of hypoxia and negative outcomes. This could be addressed by training with the device and potential modifications to design. When the airway Box was utilized, participants reviewed the box positively, yet the box was only reviewed 38 times. This suggests the difficulty to acquire provider adherence regardless of their own perceived benefit to their personal safety. If further research supports use of the device, the question may be asked if the device warrants a mandated protocol until sufficient adherence of use is acquired. National organizations could make recommendations supporting use but to gain support several unanswered questions regarding the device would need to be investigated.

Time is of the essence and it is becoming more apparent as this pandemic rage on that the challenges recognized during the outbreak require innovative solutions. Our data supports the emergence of the airway box as a possible addition to PPE and suggest further research and implementation. This study did not attempt to address possible modifications to the box that could address concerns established in other studies. One possible adjustment to device manufacturing could be the addition of suction and glove boxes to the device. The addition would not alter function, provider view, ease of operation but could limit any viral particles that would normally escape the device. This device will not eliminate the risk of exposure, but we hope it can significantly decrease risk in an effort towards creating a safer hospital with stepwise implementation of sensible PPE, without impacting patient quality of care or expense. Approximately 9% of SARS-CoV-2 patients require ICU admission and of that group 88% require intubation and mechanical ventilation [10]. The airway box is therefore a leading contender to mitigate the risk during the procedure. The implications of this device could result in its addition to the SARS-CoV-2 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), with provider use adherence and sufficient device availability. Feedback from healthcare providers in our study supports the efficacy of the device to decrease the direct exposure. 54% of the providers felt the device increased safety from exposure while only 16% found the device to decrease safety. Our study design did not attempt to evaluate the rooms’ aerosolization particle concentration; however, we have considered the research from Melbourne Australia suggesting the potential total viral load increase [11].

This study’s conclusion does not reference that the box is not pressurized and should not affect the overall aerosolization created during the event of aspiration or coughing. Specifically, they find that the aerosolization boxes may increase airborne particles through the holes in the box. The study uses saline nebulizers in large quantities to assess the efficacy of the different barrier methods. The large quantity nebulization may skew the results in a way that does not represent standard intubation or extubation. The device prevents the direct spray of particles to the healthcare provider. Particle concentration in the air is significantly affected by air circulation, humidity, and atmospheric pressure within the room. The device has two 6.5-inch radius holes and does not create a pressurized spray from a standard intubation. If the researchers used a high-pressure system that did result in this affect, it may not be representative of the standard execution and outcome of the procedure. The air within an operating room circulates at an average rate of 18-26 cycles per hour which helps alleviate some of the risk that may result using the Airway box.

While we have not overlooked this study, it is important to consider risk-reward for the provider performing intubation. The room circulation paired with the standard PPE helps to decrease the impact of air particles within the room. Implementation of “aerosol clearance time” can help with room contamination. The study referenced above by Dr. Canelli illustrating the particle distribution during procedure and noted the aerosolization particle spread to a 2-meter radius without the use of the device and with the device contained the spray within the box. In this study, we have concluded that the Airway Box could serve as a productive barrier enclosure mechanism to limit potential spread during intubation but insist further research and modifications like addition of suction in the box should be conducted to evaluate the efficacy.

Conclusion

Modifications, and improvements to emerging barrier enclosure devices like addition of suction, glove holes and clear drapes may provide added benefit to frontline clinicians. Unfortunately, like a mask mandate, there will be significant resistance to change and implementation until it becomes standard of practice. We recognize many institutions and clinicians may be slow to adapt from currently employed standards of practice. Due to the magnitude and ramifications of this pandemic it may be prudent to including mandated use of this device until its practice is accepted as normal operating procedure.

References

- Weissman DN, de Perio MA, Radonovich LJ (2020) COVID-19 and Risks Posed to Personnel During Endotracheal Intubation. JAMA 323(20): 2027-2028.

- Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J, et al. (2012) Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PloS one 7(4): e35797.

- Canelli R, Connor CW, Gonzalez M, Nozari A, Ortega R, et al. (2020) Barrier enclosure duringendotracheal intubation. New England Journal of Medicine 382(20): 1957-1958.

- Jayaweera M, Perera H, Gunawardana B, Manatunge J (2020) Transmission of COVID-19 virusby droplets and aerosols: A critical review on the unresolved dichotomy. Environmental Research,109819.

- (2019) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 46. WHO.int, World Health Organization, Mar. 2020, 10:00.

- Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS (2020) False Negative Tests for SARS-CoV-2 Infection-Challenges and Implications. New England Journal of Medicine 383: e38.

- Schutzer‐Weissmann J, Magee D J, Farquhar‐Smith P (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection risk during elective peri‐operative care: a narrative review. Anaesthesia 75(12):1648-1658.

- Wvutoday (2020) WVU Today: WVU-Engineered Intubation Boxes to Help Reduce Risk to Clinicians duringCOVID-19 Pandemic. WVU Today | West Virginia University, 16 Apr. 2020.

- Begley J L, Lavery KE, Nickson CP, Brewster DJ (2020) The aerosol box for intubation in COVID‐19 patients: an in‐situ simulation crossover study. Anaesthesia 75(8): 1014-1021.

- Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, et al. (2020) Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. Jama 323(16): 1574-1581.

- Simpson JP, Wong DN, Verco L, Carter R, Dzidowski M, et al. (2020) Measurement of airborne particle exposure during simulated tracheal intubation using various proposed aerosol containment devices during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Anaesthesia 75(12): 1587-1595.

Opinion

Opinion