Abstract

Background: Neuroendocrine neoplasm is a relatively common type of tumor. But the diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasm in gastrointestinal tract is challenging.

Purpose: To investigate the clinical and imaging features of neuroendocrine tumors in different locations of the gastrointestinal tract.

Material and methods: Clinical and imaging data were collected from 58 cases of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors diagnosed by surgery or puncture pathology plus immunohistochemistry between January 2010 and April 2018 at the Southern Medical University Nanfang hospital.

Results: In the CT plain scan, when the mass was small, it showed equal density with a clear boundary. When the mass was large, liquefaction and necrosis was apparent, and the boundary was less clear. In the contrast CT scan, the lesions continued to strengthen, showing “fast forward and slow exit”. metastasis lesions were found in lymph node (6), hepatic (9), bone (3), lung (1), adrenal (1). P values for tumors at different sites for grading, staging, Syn, CgA, and size were 0.001, 0.00, 0.006, 0.008, 0.002, and 0.000; the gender P value was 0.09.

Conclusion: Differences in grading, staging, Syn and CgA expression, size, and enhancement were statistically significant (P˂0.05). Endocrine tumors that occur in the esophagus/stomach are more malignant than endocrine tumors of the rectum. They were significantly enhanced in duodenal lesions, but mildly enhanced in rectal lesions; With an enhancement pattern of “fast-forward and slow-out”.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal Tract; Neuroendocrine Neoplasms; Multi Slice Spiral CT; Diagnosis

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are a group of malignant tumors that originate from neuroendocrine cells and peptidergic neurons. Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine neoplasm is a relatively common type of neuroendocrine tumor that appears as a submucosal mass, differentiates in the direction of neuroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract, and accounts for 1.2–1.5% of all of the gastrointestinal tumors [1]. The incidence of GINETs has recently begun to show a steady increase. Pearsow [2] reported in 1949 that a group of neuroendocrine tumors had metastasized, making people realize that neuroendocrine tumors may be malignant. Although neuroendocrine cells are located throughout the body, over 66.7% of neuroendocrine tumors appear in the gastrointestinal tract, 25% in the lungs, and the remaining 10% in other parts of the body [3]. The digestive system was the most common site of NENs, and the stomach was ranked fourth, followed by the small intestine, rectum, and pancreas [4]. As the clinical manifestation of GI-NENs is not specific, diagnosis usually occurs late in the natural course of the disease. The diagnosis of GI-NENs is quite challenging. Through the study of the clinical features and CT images of neuroendocrine tumors in different sites of the gastrointestinal tract, this paper summarizes the diagnostic features that may improve clinical diagnosis and grade of the disease.

Methods

Clinical Data

Fifty-eight cases of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors diagnosed by surgery or puncture pathology and immunohistochemistry between January 2010 and April 2018, the study obtained the patients’ informed consent and was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of the Southern Medical University Nanfang hospital. of which 47 cases underwent CT examination and 43 cases underwent contrast CT scan. The GE Light Speed 16 CT was utilized, and the scanning parameters were as follows: tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current 250mAs; slice thickness, 7.5 mm; slice interval, 7.5 mm; and beam pitch 1:1. The contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed using the non-ionic contrast agent Iohexol, which was injected through the elbow vein with a high-pressure syringe. The total amount was 60–100 ml, the injection flow rate was 3–5 ml/s (arterial phase, 25–30s; the portal vein, 50–60s), and the delay period was 3–5 min. After scanning, the image was transmitted to the workstation for reconstruction and analysis.

All of the images were retrospectively analyzed by two senior radiologists. The following imaging parameters were reviewed: tumor location, size, tumor margin (well-circumscribed or illdefined border), edge/morphological features (intraluminal mass or wall thickening), and enhancement degree (mildly enhanced, CT values < 20 HU; moderately enhanced, CT values 20-40 HU; severely enhanced, CT values > 40HU). The region of interest (ROI) was placed in the same region at different times, with a size of 0.4–1.0 mm2. Lymph nodes and distant metastases were recorded. Lymph nodes larger than 10 mm in diameter were marked as metastases.

Pathology

Pathologic diagnosis and classification were confirmed by two physicians in the Department of Pathology of the Southern Medical University Nanfang Hospital. We performed immunohistochemical staining on the surgically resected tissues to detect the expression of Ki-67, CgA and Syn, and choose whether to determine the expression of NSE according to each individual situation. We used the Dako REALTM EnVisionTM staining system for staining. After dewaxing, hydration, and antigen retrieval of paraffin-embedded tissue, PBS was removed, and the primary antibody was added and incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature. Tissues were then rinsed with PBS 3 x for 3 min, PBS was removed, and the secondary antibody MaxVisionTM/HRP was added and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Tissues were then rinsed 3 × for 3 min, dried, and dripped with freshly prepared DAB; tap water was used to stop color development at the appropriate time, and then the chlorophyll was re-dyed. Hydrochloric acid alcohol was used to differentiate ammonia water to blue, gradient alcohol was used for dehydration, and neutral gum was used to seal. International standards were used to interpret the results of the immunohistochemical staining.

Grading Standard

GEP-NENs were graded according to the 2010 consensus of Chinese experts on gastrointestinal pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Using the number of mitotic figures and the Ki-67 index, GEP-NENs were divided into NET1 grades (NET G1: < 2 mitoses per 10 HPF, Ki-67 ≤ 2%; NET G2: 2–20 mitoses per 10 HPF, Ki-67 index 3% to 20%; and PNEC G3: > 20 mitoses per 10 HPF, Ki-67 index > 20%).

Staging Standard

Tumor staging was performed using the 2010 7th edition of the American Cancer Research Association (AJCC) TNM staging standard, which includes the size and degree of invasion (T), lymph node metastasis (N), and distant metastasis (M) of malignant tumors.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 17.0 statistical software package. The mean ± standard deviation was used for counting. We compared the gender/gradation/stage/Syn/ CgA of the neuroendocrine carcinomas at different sites using the chi-square test, and then analyzed tumor size and enhancement by one-way analysis of variance; P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Date

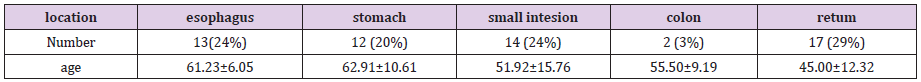

Fifty-eight patients were included in the study (36 males and 22 females aged 27-77 years, with an average age of 54.3 years). Of the cases, 13 occurred in the esophagus, 12 in the stomach, 14 in the small intestine, 2 in the colon, and 17 in the rectum (Table 1). The clinical manifestations varied from site to site. The main clinical manifestation in esophageal cancer was progressive dysphagia with a history of more than 10 days to 1 year. The main manifestations in the stomach were upper abdominal pain/bloating, with a history of more than 10 days to 1 year, among which 1 case was found by medical examination and 1 case had melena. Main clinical manifestations of the small intestine included repeated abdominal pain/bloating, with a history of more than 10 days–10 years, of which one patient presented with yellow-staining of the sclera/ skin and yellow urine, one with recurrent vomiting and diarrhea, and one with melena. The major clinical manifestation in the colon was abdominal distension, with a duration of 3–4 months; one case had melena. Main manifestations of the rectum included bowel habit change/blood in the stool for 15 days–3 years, and 5 cases were found by physical examination.

Gross/Microscopic Pathology and Immunohistochemistry

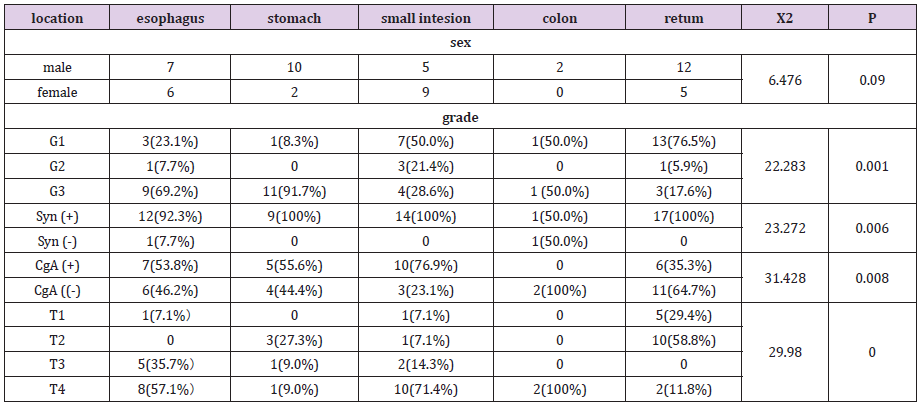

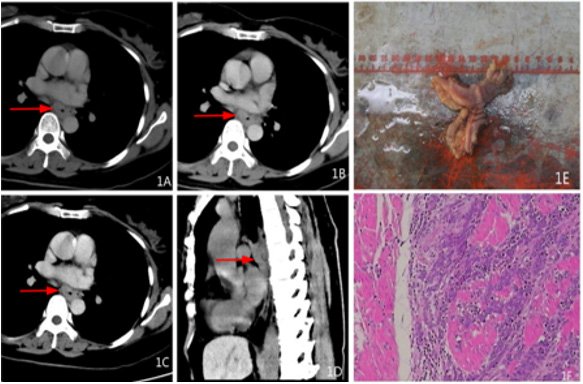

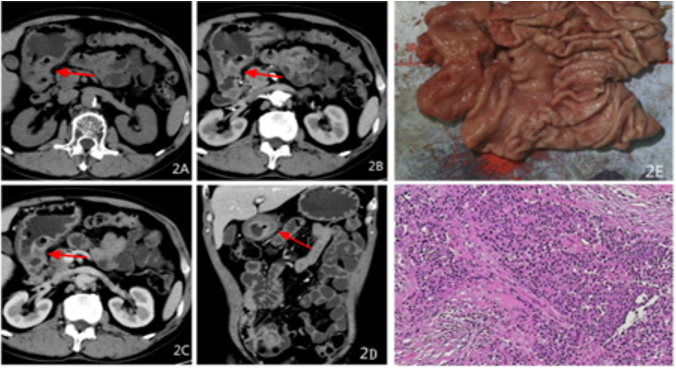

Gross/mirror: of the 58 patients there were 25 cases of G1, 5 cases of G2, 28 cases of G3; 7 cases of T1, 14 cases of T2, 8 cases of T3, 29 cases of T4 (Table 2); Twenty-one cases had visible tumors and 37 cases exhibited thickening of the gastrointestinal wall where the section (cutting face) was grey-white stiff or yellow-gray tough. Microscopically, tissue tumor cells were observed to have an adenoid/nest-like/cord-like arrangement with infiltrating growth, small size, round or oval, a large and deep nucleus, undergoing partial mitosis, and with proliferation of interstitial fibrous tissue with inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 1E.1F; 2E.2F).

Immunohistochemistry: In this group of patients, we mainly detected the expression of chromogranin A (CgA), synaptic binding protein (synaptotagmin, Syn), and neuron specific enolase (NSE) in different sections (Table 2).

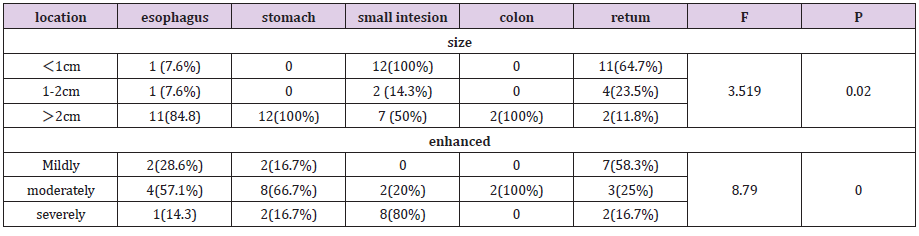

CT Imagines

Forty-seven of the 58 patients received CT examination; 21 cases showed equal density masses and 22 showed tube wall thickening. Lesions were less than 1 cm in 11 cases, 1–2 cm in 12 cases, and larger than 2 cm in 24 cases. In the plain scan, the smaller masses were of equal density, and the boundaries were clear. In larger masses, liquefaction necrosis occurred, and the boundary was not clear. In the enhanced scanning lesions continued to enhance, showing an enhancement pattern of “fast-forward and slowout.” The venous phase showed slight enhancement in 11 cases, moderate enhancement in 19 cases, and severe enhancement in 14 cases; 6 cases had lymph node metastasis, 9 had liver metastases, 3 had bone metastases, 1 had lung metastasis, and 1 had adrenal metastasis (Figures 1-4 and Table 3).

Figure 1: Female, 49 years old, dysphagia for a year, pathological diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma G3, 1A transverse CT scan +.1B transverse position CT arterial phase +1C transverse position CT venous phase +1D sagittal CT venous phase: The middle wall of esophagus is thickened, the boundary is clear, and the arterial phase is moderately enhanced, and the venous phase is continuously strengthened. 1E gross pathology +1FHE staining: tumor invasive growth, destruction of the esophageal mucosa, microscopic tumor cells small, round or round, less cytoplasm, large nuclear stain, mitotic figures visible.

Figure 2: Male, 64 years old, intermittent upper abdominal pain for more than 4 months, aggravated for more than 10 days, pathological diagnosis of neuroendocrine cancer G3 grade, 2A transverse position CT plain scan + 2B transverse position CT arterial phase + 2C transverse position CT venous phase + 2D coronal position CT venous phase: the wall of the antrum is thickened, the boundary is unclear, low-density necrotic foci can be seen, the arterial phase is slightly enhanced, and the venous phase is continuously strengthened. 2E gross pathology + 2FHE staining: tumor invasive growth, destruction of the mucosa, ulcer formation, microscopic tumor cells small, nuclear bias, size, visible abnormal.

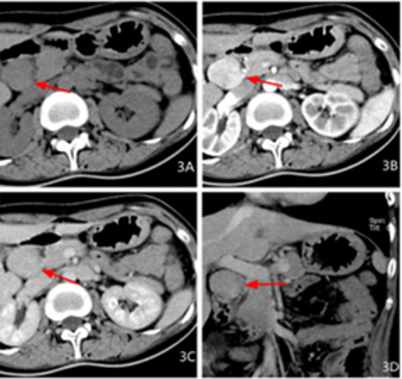

Figure 3: Female, 27 years old, abdominal distension for more than 3 months, intermittent black stool for 2 days, pathological diagnosis for neuroendocrine carcinoma G2, 3A transverse CT scan + 3B transverse CT coronary artery + 3C transverse CT venous + 3D coronal CT venous phase: a swollen shadow between the pancreatic head and the duodenum, the boundary is clear, the density is uniform, the arterial phase is obviously enhanced, and the venous phase is lessened.

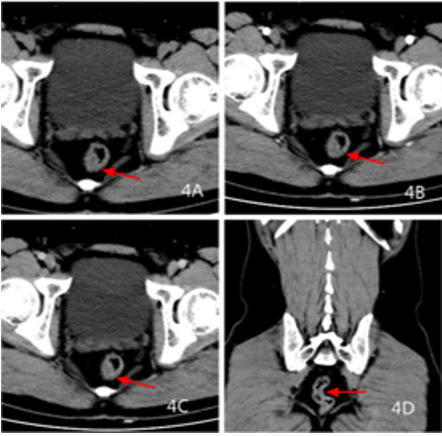

Figure 4: Male, 38 years old, colonoscopy examination, pathological diagnosis of neuroendocrine cancer G1, 4A transverse CT scan +4B transverse CT artery +4C transverse CT venous +4D coronal CT venous: rectal wall Uneven thickening, clear boundary, mild enhancement of scanning in arterial phase, continuous strengthening of venous phase, peripheral fat gap is clear.

Statistical Results

The grading, staging, Syn, CgA, size, and enhancement P values of tumor in different sites were 0.001, 0.00, 0.006, 0.008, 0.002, and 0.000, respectively. The gender P value was 0.09 (Table 2).

Discussion

Most gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors originate from enterochromaffin (ECL) cells. Neuroendocrine tumors can act by increasing the circulating adenine monophosphate in target cells and secreting a large amount of vasoactive substances, including serotonin and histamine, in addition to peptide hormones. In the experimental group from this study, one patient with a lesion in the duodenum had repeated vomiting/diarrhea. The laboratory examination showed that serotonin was elevated, indicating that the patient had carcinoid syndrome. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors are less likely to develop carcinoid syndrome. In this group, only 1 case (1.7%) was associated with the secretion of less active substances by the tumor.

SEER Database analyses showed that the incidence of GEPNENs was the highest in the small intestine, followed by the rectum, colon, stomach, and appendix. The incidence of cancer in these sites, especially in the rectum and small intestine, is increasing each year. a study on 25,531 patients found that the incidence of neuroendocrine tumors in males and females was close to a 1:1 ratio [5,6]. There were 58 cases in the experimental group, approximately 77.9% of which were over 40 years old, with 36 males and 22 females. The age of onset was old and men were more likely to have the disease than women, which is not consistent with other reports. The clinical symptoms and signs of these patients were not obviously specific, similar to other digestive tract tumors. Six patients exhibited no specific clinical manifestations and they were found by physical examination. Therefore, routine gastrointestinal endoscopy is helpful for the early detection of rectal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Surgery is the mainstay for the treatment of locoregional GI-NETs. Endoscopic resection is an option for well-differentiated early GI-NETs, which are thought to very rarely metastasize to lymph nodes [7].

Detection of CgA/NSE/Syn expression in tumor tissues by immunohistochemistry is helpful for the diagnosis of NETs [8]. The most useful biomarker of neuroendocrine tumors in clinical practice has been chromogranin A, which is the product of neuroendocrine granules and can be measured in serum or plasma samples [9,10]. It has been reported that the positive expression rate of Syn is 95.62% and CgA is 77.1% in gastrointestinal endocrine tumors [11]. The positive expression rate of pathological Syn in the experimental group was 96.3% and CgA was 51.9%. The level of Syn expression is consistent with the literature, while CgA expression was lower than other literature. As the sensitivity and specificity of different biomarkers depends on the location of the primary tumors, CgA expression was mainly used in patients with pancreatic and midgut NET. This group did not include the pancreas, and the positive rate was lower than that reported in the literature. CgA is associated with tumor staging and metastasis and is increased in patients with metastatic disease [11,12].

Various studies have also shown that patients with larger liver metastases have higher levels of CgA. In the experimental group, the positive rate of CgA in the esophagus/stomach/small intestine was higher than that in colorectal cancers. This may be related to the larger lesions and higher grade in the esophagus/ stomach/small intestine cancers. The enzyme NSE is most useful in patients with poor NET differentiation [13]. In this group, there were 7 cases of NSE (+) and 6 cases of G3, which is consistent with the literature. Forty-seven patients in this group underwent CT examination, and lesions were found in 43. The detection rate of the CT was approximately 91.4%. Three lesions were located in the rectum, and one duodenal lesion (Graded as G1) was not detected by CT. Pathology showed that this lesion was less than 1 cm. CT scan had poor results for the detection of small lesions in the rectum, which may have been influenced by enema or that had not been fully cleaned. Esophageal endocrine cancer, located in the lower part of esophagus, had a larger lesion range (3.3–8.8 cm). The main CT manifestations were the thickening of the wall, an unclear boundary, uneven density, low density necrosis, mildly moderate enhancement, visible ulcers on the surface, and mild dilatation at the upper esophagus. Four cases had lymph node metastasis, 2 had liver metastasis, and 1 had lung metastasis. Malignant esophageal endocrine tumors are more common and prone to metastasis.

As reported by Maru DM [14] NEN in the esophagus are more likely to be malignant, which is consistent with the results of our research. Since esophageal endocrine cancer lesions are located under the mucosa, the softness of the early wall remains normal, and clinical symptoms are not easily detected. Therefore, it is difficult to detect lesions in the early stage. Gastric endocrine tumors were located in the gastric fundus in 4 cases, the gastric body in 5 cases, and the gastric antrum in 2 cases. Four cases exhibited a mass, 7 cases had invasive growth, a thickened wall, and an unclear boundary with a normal stomach wall, and 3 cases exhibited ulcer, enhanced scanning to severe reinforcement, continuous enhancement, and a fast forward and slow out enhancement pattern. Four cases presented as lumpy, seven cases exhibited invasive growth with a thickened wall, and the boundary with the normal gastric wall was not clear. Three cases were ulcerated, and severe enhancement was observed in the enhanced scanning, which continued to enhance, showing a fast in and slow out enhancement pattern. Gastric endocrine tumors are more likely to be malignant, and the lesions are mostly G3. These highly aggressive neoplasms are traditionally treated with platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with etoposide. Immune checkpoint inhibitors might be the future treatment [15].

Considering that the clinical symptoms of gastric endocrine carcinoma are not specific, and the manifestations are similar to chronic gastritis, gastric endocrine carcinoma are easily neglected. Complete resection is the only treatment when the stomach is the more aggressive component [16]. Endocrine tumors of the small intestine were mainly located in the duodenum, accounting for about 71% of cases. Over 66.7% of the duodenal neuroendocrine tumors were gastrinomas. An intraluminal mass is the most common, with a clear boundary between the tumor and surrounding tissue. Enhanced scanning showed obvious enhancement, in which moderate enhancement was 28% and severe enhancement was 72%. Among these cases, 2 were significantly enhanced in the arterial phase and significantly reduced in the venous phase. Clinical laboratory examination revealed high CA199, CEA and CgA(- ),indicating that the tumor may be combined with adenocarcinoma. Since duodenal masses grow into the lumen, especially in the duodenal ampulla, early clinical symptoms can be obvious. The lesions can be found by patients in the early stage and the grade is generally low. However, since the endocrine cancer originates from the submucosa, the staging and grading are inconsistent.

One case showed clinical yellow-staining of the skin/sclera and yellow urine. CT showed that the lesion was located in the duodenal papilla and it was small (approximately 1 cm), but the clinical obstruction symptoms were very obvious and easily caught the patient’s attention. Colonic endocrine tumors are very rare. In this group, only 2 cases were located in the lumen. Colonic endocrine tumors grow into a mass in the lumen, the lesions are large, uneven in density, and low-density necrotic lesions can be seen. The ulceration of one case could be seen on the surface of the mass, and the scan was moderately enhanced. Only 1 case developed intestinal obstruction. The two patients had elevated CEA and CgA(- ) Takizawa et al. [17]. examined 25 colorectal NECs and concluded that the molecular characteristics of colorectal NEC are like those of adenocarcinoma, considering that the tumor is accompanied by adenocarcinoma. The incidence of rectal endocrine cancer was the highest, with a small lesion volume and thickening of the wall as the main manifestation. The peripheral fat gap was clear, and the enhanced scan was mildly to moderately enhanced. Tumors in G1 were common, with 13 cases, accounting for 76%.

The T1/ T2 lesion was also common, with 15 cases accounting for 88% of cases. Due to the small size of rectal lesions, intestinal preparation is very important. If rectal endocrine tumors are suspected, it is important to clean the area with an enema before examination. With the emphasis on colonoscopy, many rectal endocrine tumors are found prior to the onset of symptoms, which may be the reason for the higher number of G1 lesions reported for rectal endocrine tumors. Lymph node and distant metastases can be seen in endocrine carcinomas of the digestive tract. The pathology of this group identified 22 cases of lymph node metastasis, but CT showed only 6 cases of lymph node metastasis; therefore, the detection rate was only 27.3%. Tanaka T [18] reported that lymph nodes larger than 5 mm on the CT image are predictors of perioperative/rectal regional lymph node metastasis. The sensitivity and specificity of the standards were 66.7% and 87.5%, respectively, and the AUC was 0.844. We used lymph nodes larger than 1 cm as a predictor of lymph node metastasis, which reduced the predicted value. It is possible that some lymph nodes do not increase significantly even though metastasis has already occurred. Therefore, the standard for metastases should be 5 mm. In NETs, the possibility of lymph node metastasis is defined by the size and depth of invasion; Lymph node dissection is useful for lesions that are at high risk for lymph node metastasis [19].

Therefore, preoperative diagnosis is essential for lymph node dissection during tumor resection. Distant metastasis of endocrine cancers of digestive tract can occur in the liver/lung/bone/adrenal gland; however, metastasis occurs most commonly in the liver. peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) was one of the most effective therapeutic options for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), improving progression-free survival and overall survival [20].

In conclusion, CT of endocrine carcinomas of the digestive tract showed intraluminal masses or invasive wall thickening. Esophageal/rectal lesions mainly show thickening of the wall. Duodenal/colonic lesions mainly show masses, and enhanced scanning showed duodenal lesions were obviously enhanced. The rectal lesions were slightly enhanced and exhibited a “fastforward and slow-out” enhancement pattern, which continued to enhance. This feature can distinguish lesions from intestinal adenocarcinoma. CT examination can not only confirm the location of the tumor, but also indicate the stage and degree of the tumor. This is a rare disease; accurate diagnosis is important to determine the treatment plan. Therefore, it is necessary to perform CT examination on patients before surgery.

Authors ‘Contributions

Xiaofeng He conceived and designed the study. Jincheng Li collected datas, Bihong Xu provided administrative support. Shuiying Tang wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by Dean Fund of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2017B016) and Industrial Technology Research and Development Funds (K1050215).

References

- (2016) Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology Neuroendocrine Oncology Expert Committee, Chinese gastrointestinal pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor expert consensus (2016 edition) [J]. Chinese Clinical Oncology 21(10): 927-946.

- Pearson CM, PJ Fitzgerald (1949) Carcinoid tumors; a re-emphasis of their malignant nature; review of 140 cases. Cancer 2(6): 1005-1026.

- Ellis L, MJ Shale, MP Coleman (2010) Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: trends in incidence in England since 1971. Am J Gastroenterol 105(12): 2563-2569.

- Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, et al. (2017) Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol 3(10): 1335-1342.

- Mocellin S, D Nitti (2013) Gastrointestinal carcinoid: epidemiological and survival evidence from a large population-based study (n = 25 531). Ann Oncol 24(12): 3040-3044.

- Avenel P, McKendrick A, Silapaswan S, Kolachalam R, Kestenberg W, et al. (2010) Gastrointestinal carcinoids: an increasing incidence of rectal distribution. Am Surg 76(7): 759-763.

- Eto K, Yoshida N, Iwagami S, Iwatsuki M, Baba H (2020) Surgical treatment for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery 4(6): 652-659.

- Yaru Chai, Jianbo Gao, Pan Liang (2015) The CT findings and clinicopathological features of gastric neuroendocrine tumors[J]. Chinese Journal of Clinicians (Electronic Edition) 9(13): 2611-2615.

- Wang Z, Li W, Chen T, Yang J, Luo L, et al. (2015) Retrospective analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Exp Ther Med 10(3): 1084-1088.

- Modlin IM, Bjorn I Gustafsson, Steven F Moss, Marianne Pavel, Apostolos V Tsolakis, et al. (2010) Chromogranin A--biological function and clinical utility in neuro endocrine tumor disease. Ann Surg Oncol 17(9): 2427-2443.

- Xin Gao, Chunxi Xu, Lingchuan Guo, Weishuo Liu (2015) Epidemiological and clinicopathological features of 146 cases of digestive system neuroendocrine tumors in Suzhou area. Shandong Medicine (44): 45-47.

- Yao JC, Pavel M, Phan AT, Kulke MH, Hoosen S, et al. (2011) Chromogranin A and neuron-specific enolase as prognostic markers in patients with advanced pNET treated with everolimus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(12): 3741-3749.

- Tirosh A, Papadakis GZ, Millo C, Sadowski SM, Herscovitch P, et al. (2017) Association between neuroendocrine tumors biomarkers and primary tumor site and disease type based on total (68)Ga-DOTATATE-Avid tumor volume measurements. Eur J Endocrinol 176(5): 575-582.

- Maru DM, Khurana H, Rashid A, Correa AM, Anandasabapathy S, et al. (2008) Retrospective study of clinicopathologic features and prognosis of high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 32(9): 1404-1411.

- Ali AS, SW Langer, Federspiel B, Hjortland GO, GrOnbaek H, et al. (2020) PD-L1 expression in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms grade 3. PLoS One 15(12): e0243900.

- Takahashi K, Fujiya M, Sasaki, Sugiyama Y, Murakami Y, et al. (2020) Endoscopic findings of gastric mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(38): e22306.

- Takizawa N, Ohishi Y, Hirahashi M, Takahashi S, Nakamura K, et al. (2015) Molecular characteristics of colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma; similarities with adenocarcinoma rather than neuroendocrine tumor. Hum Pathol 46(12): 1890-1900.

- Tanaka T, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Hata K, Kiyomatsu T, et al. (2017) Lymph Node Size on Computed Tomography Images Is a Predictive Indicator for Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients with Colorectal Neuroendocrine Tumors. In Vivo 31(5): 1011-1017.

- Saund MS, Al Natour RH, Sharma AM, Huang Q, Boosalis VA, et al. (2011) Tumor size and depth predict rate of lymph node metastasis and utilization of lymph node sampling in surgically managed gastric carcinoids. Ann Surg Oncol 18(10): 2826-2832.

- Liberini V, Huellner MW, Grimaldi S, Finessi M, Thuillier P, et al. (2020) The Challenge of Evaluating Response to Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: The Present and the Future. Diagnostics 10(12): 1083.

Research Article

Research Article