Abstract

Introduction: Dermatitis herpetiformis or also known as Duhring’s Disease or gluten rash is an autoimmune vesicobulose disease, this disease is not related to dermatitis, nor is it caused by the herpes virus, but a specific and recurrent chronic skin condition associated with celiac disease and gluten-sensitive enteropathy. The main predisposing factor is genetics, this is related to Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLAs) DQ2 and DQ8. Dermatitis herpetiformis can affect any age but appears more often for the first time in young adults between the ages of 30 and 40, more often in men than in women, where the lesions in men are common in the mouth and genitalia.

Discussion: The main lesions are erythematous papules, plaques, urticaria, or most commonly vesicles, of which large bullae rarely occur. The lesions seen in people with dermatitis herpetiformis may be crusted and may not show the main lesion. On physical examination, excoriation and erosion are common. The distribution of lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis is symmetrical with a frequent predilection of the extensor surfaces of the forearms, elbows, shoulders, knees, buttocks and back. The main therapeutic management of dermatitis herpetiformis is a gluten-free diet. Adherence to a strict gluten-free diet resulted in resolution of symptoms of dermatitis herpetiformis and a positive development of intestinal pathology. Despite implementing a non-strict gluten-free diet, the accumulation of IgA in the dermoepidermal junction in dermatitis herpetiformis patients will slowly disappear and may take several years to completely disappear.

Conclusion: The management of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis should be a team consisting of a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist and a nutritionist. Patients require follow-up to monitor long-term medication use and control recurrence of symptoms. Regular visits will facilitate screening and early detection of autoimmune conditions or neoplasms that may be associated with dermatitis herpetiformis and to obtain referral therapy for patients experiencing them.

Keywords: Duhring Disease; Dermatitis Herpetiformis; Diagnosis; Management

Introduction

Dermatitis herpetiformis or also known as Duhring’s Disease or gluten rash is an autoimmune vesicobulose disease, this disease is not related to dermatitis, nor is it caused by the herpes virus, but a specific and recurrent chronic skin condition associated with celiac disease and gluten-sensitive enteropathy. The main predisposing factor is genetics, this is related to Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLAs) DQ2 and DQ8 [1-3]. This disease was first discovered by Dr. Louis Dühring in 1884 was marked by complaints of intense itching. The main lesions are erythematous papules, plaques, urticaria, or most commonly vesicles, of which large bullae rarely occur. The lesions seen in people with dermatitis herpetiformis may be crusted and may not show the main lesion. On physical examination, excoriation and erosion are common. The distribution of lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis is symmetrical with a frequent predilection of the extensor surfaces of the forearms, elbows, shoulders, knees, buttocks and back [1,4,5].

Dermatitis herpetiformis can affect any age but appears more often for the first time in young adults between the ages of 30 and 40, more often in men than in women, where the lesions in men are common in the mouth and genitalia [1,2,4]. Antibodies in transglutaminase tissue and epidermal transglutaminase can be measured serologically. To make the diagnosis, a skin biopsy and direct immunofluorescence examination is needed which shows granular IgA deposits in the papillary layer of the dermis. This disease can be distinguished from other vesicle eruption diseases by histologic, immunological and gastrointestinal criteria [3,6,7]. Gluten-free diet is the first-line therapy that can relieve the manifestations of the skin and intestinal conditions, while the results of therapy of dapsone and sulfones are only on skin eruptions. Combined therapy with a gluten and dapsone-free diet is the initial treatment option for controlling skin manifestations in dermatitis herpetiformis. Aim of the article to review diagnosis and management for Duhring disease [1,3].

Discussion

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a rare vesicobulosa dermatitis. The incidence and prevalence of dermatitis herpetiformis is not well known. In a study conducted in Finland in 1978, the prevalence of dermatitis herpetiformis was 10.4 per 100,000 population and the annual average incidence was 1.3 per 100,000 population.2 While a study in United States in 2014 showed the prevalence of dermatitis herpetiformis was 11.2 cases per 100,000 population. The prevalence of dermatitis herpetiformis in Caucasians is between 10 and 39 per 100,000 population [1,2,8]. Dermatitis herpetiformis occurs more frequently in people of Northern European descent and the disease is rare in people of Asian and African descent. Dermatitis herpetiformis occurs most frequently in Irish and Swedish people. This may be associated with HLA associated with Dermatitis herpetiformis and Celiac disease including DQA 1 * 0501 and B1 * 02 which encode HLA-DQ2 heterodimers [8].

Although dermatitis herpetiformis is found most frequently in Europe and the United States, it is uncommon for dermatitis herpetiformis to be found among African Americans and Asians including Japanese, possibly due to differences in the frequency of the HLA antigen associated with dermatitis herpetiformis [2,6]. A 30-year population-based study of 1147 patients with celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis in Finland also revealed that overall patients with dermatitis herpetiformis had a good prognosis. The total incidence of malignancy was comparable in patients with celiac disease and patients with dermatitis herpetiformis, but an increased incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was also present between patients with celiac disease and patients with dermatitis herpetiformis with a standard incidence ratio of 3.2 and 6.0, respectively. Overall, the mortality rate actually decreased in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis [1,2]. Dermatitis herpetiformis can occur at any age, including children. However, it is most often found in the 2-4 decades, namely the age of 20 years to 40 years. Adolescents and prepubertal children are rarely affected. According to research data in the United States, it was found that men suffer from dermatitis herpetiformis more often than women, with a ratio of 2: 1 for international and 1.44: 1 in America [1,2,4].

Ethiology

In 1884, Louis Dühring was the first to describe the clinical picture and history of polymorphic pruritic disease, then he gave the name dermatitis herpetiformis. However, important elements in the pathogenesis of dermatitis herpetiformis were not known until the 1960s. In 1966, Marks et al. first revealed a gastrointestinal abnormality in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis. After that, in a short time, it has been revealed that the lesions are reversible by avoiding a gluten protein diet [1,4]. Initially, intestinal abnormalities are estimated to be up to 60% -75% in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. However, this statement has been modified in two ways. First, the diagnostic criteria for dermatitis herpetiformis have been described more precisely, and secondly, dermatitis herpetiformis can be recognized in certain patients who without gastrointestinal pathological features can induce the development of gastrointestinal lesions by increasing the intake of large amounts of gluten, such as patients who complain of celiac lesions. Thus, many patients with dermatitis herpetiformis have gastrointestinal abnormalities (if not identical) similar to those of celiac disease, even though the patient is consuming minimal gluten. Several studies have shown that gluten has an important role in the pathogenesis of dermatitis herpetiformis [1,4,5].

The pathophysiology of dermatitis herpetiformis appears to involve a complex of autoimmune factors such as HLA predisposition, genetics, and the environment. Both gluten sensitivity and dermatitis herpetiformis have a strong genetic component, as demonstrated in the case of monozygous twins [1,2]. Recently, a prospective study of six pairs of monozygous twins showed an average probability of developing dermatitis herpetiformis of 0.91, a higher rate of inheritance. These studies, although illustrative, were carried out on small sample sizes, which limited the statistical analysis. In addition, population-based analyzes of first-degree relations showed that the incidence of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis among first-degree relations was nearly 15 times higher than that of the general population. 18% of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis in this study had a firstdegree relationship with either dermatitis herpetiformis or gluten intolerance. These findings suggest that genetic factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of dermatitis herpetiformis and can be an interesting and clinically useful observation in counseling patients and families suffering from this disease [1,9].

Diagnosis

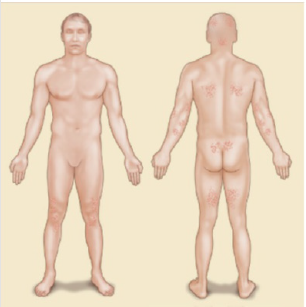

The clinical distribution and morphology of skin lesions are important markers in the diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis. The distribution of the lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis is usually symmetrical and the location of the disease is on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, the elbows, knees, scalp, back of the neck (nape), back, shoulders, sacrum area and buttocks. The face and groin can also be affected [1-3]. An illustration of the distribution of lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis can be seen in Figure 1.

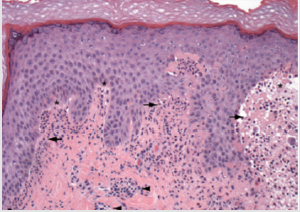

The diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis is based on a combination of physical examination, routine histopathological examination, immunofluorescence examination, and serological testing. Physical examination alone can lead to the diagnosis, but due to the varying morphological appearance of dermatitis herpetiformis, additional examinations are often required to assist in the diagnosis. Routine biopsy specimens should be taken from intact vesicles. The typical histopathological appearance of dermatitis herpetiformis when examined under a light microscope is a subepidermal cleft with neutrophils and some eosinophils in the papillary dermis as shown in Figure 2. These findings are often found along with mixed inflammatory infiltrates around the blood vessels [10].

Figure 2: Electron microscope scan in dermatitis herpetiformis. Light microscope shows neutrophiles (black arrow) and subepidermal cleft (star), and inflamation infiltrat in perivaskular (black arrow) [1].

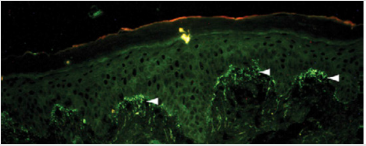

When a histopathological examination is sufficient to provide clues to the diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis, other conditions such as linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis (LABD) and bullous lupus erythematosus, can reveal a histopathological appearance which is also similar to dermatitis herpetiformis. Therefore, immunofluorescence examination is an examination that is also important for definitive diagnosis. The accumulation of granular IgA at the papillary end of the dermis in Figure 3 is a pathognomonic feature of dermatitis herpetiformis (when compared with the linear pattern of IgA buildup seen in LABD). IgA accumulation in dermatitis herpetiformis is thought to be polyclonal but mostly consists of IgA1. Occasionally granular build-up along the basement membrane occurs in dermatitis herpetiformis, which can be misdiagnosed as LABD [10,11].

Figure 3: Immunofluorosence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Direct immunofluoscence in perilesion skin shows IgA deposit in dermal papilar [11].

What is interesting is that these buildups do not change with pharmacological therapy but respond slowly well to the adoption of a gluten-free diet. The biopsy site for immunofluorescence examination plays an important role. Although IgA buildup occurs in both the lesion and non-lesion areas, a study comparing examination of the skin with lesions, perilesions, and nonlesions in dermatitis herpetiformis showed a more significant build-up of IgA when compared to normal skin around the lesion. In fact, biopsy specimens in lesions often show false negative results on direct immunofluorescence [1,2,10,11]. Serologic testing is a useful adjunct to studies that study tissue. Several serological markers show a similarity between celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis, so it is thought that these two diseases are closely related.

IgA antibodies circulating in the circulating endomisium, the tissue sheath covering muscle fibers, were detected in these two diseases [1,3,11]. The test for anti-endomisials is based on indirect immunofluorescence using the monkey’s esophagus as the substrate, although there are some operator-dependent variables, this test has a high specificity value and medium sensitivity value for diagnosing dermatitis herpetiformis. The IgA antitissue transglutaminase test was carried out using a widely available ELISA-based method, with a specificity value of 97.6% to 100% and a sensitivity value of 48.8% to 89.1%. This test may be useful in differentiating dermatitis herpetiformis from LABD and reflects the degree of mucosal changes in small bowel biopsy specimens in patients [1,8,11].

With the discovery of epidermal transglutaminase (eTG) as a key antigen in dermatitis herpetiformis, the serological test for these autoantibodies has attracted the attention of many. A recent study reported high sensitivity (60% -80.8%) and high specificity (92.8% -100%) in the serological test for dermatitis herpetiformis with the commercially available ELISA-based test for detection of IgA antibodies. anti-eTG [1,7,8]. Serologic testing offers the advantage of being cheaper and less invasive than skin biopsy, which is deferred for further validation, which would be useful as an initial screening method in clinically suspected patients. suffering from dermatitis herpetiformis. The levels of anti-tTG and anti-eTG IgA correlate with the extent to which pathological processes have occurred in the small intestine. Finally, the levels of anti-endomycial, anti-tTG and anti-eTG antibodies were found to be low in patients on a gluten-free diet and therefore testing for these antibodies may act as qualitative markers in line with the patient’s diet regimen. Although promising, the anti-eTG assay has not been approved for use in the United States for in-vitro use as the benchmark diagnosis for dermatitis herpetiformis [6-8].

Selective IgA deficiency was found to be 10–15 times higher in prevalence in patients with celiac disease than in the general population. The presence of selective IgA deficiency often delays the diagnosis of celiac disease because of the low rate of detection of IgA autoantibodies during serologic testing. No cases of selective IgA deficiency in dermatitis herpetiformis have been reported so far, suggesting a critical role over IgA autoantibodies in the skin lesions of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. However, partial deficiency has been reported in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis and should be considered in serological examination. In patients with IgA deficiency, IgG and endomycial antibodies and transglutaminase may be useful for monitoring dermatitis herpetiformis [1,2,3].

Genetic testing to determine a patient’s HLA halotype can be useful in cases where dermatitis herpetiformis cannot be excluded. Absence (HLAs) -DQ2 or -DQ8 has a high negative predictive value, as patients who have this number of alleles will suffer less often from dermatitis herpetiformis. However, because the prevalence of this allele in the general population tends to be high, a positive test is not sufficient to confirm a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis. Therefore, genetic testing is not recommended as part of routine screening for dermatitis herpetiformis [1,2]. Small bowel biopsy specimens are usually not required for examination of dermatitis herpetiformis. Because of the high sensitivity and specificity of the serological test and the typical clinical definition of dermatitis herpetiformis, this additional tar invasive examination will not change the diagnosis and treatment in the majority of dermatitis herpetiformis patients. However, if clinical signs of gastrointestinal abnormalities or malignancy are found at the time of the examination, imaging and other additional examinations may need to be indicated [10-12].

Because a significant number of dermatitis herpetiformis patients develop other immune-related conditions in them, screening for dermatitis herpetiformis may need to be indicated. Likewise, a patient screened for thyroid disease should have both his TSH and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody titres checked. The detection of elevated anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies in normal TSH is useful in identifying patients who will develop thyroid disease in the future. Measurement of blood glucose levels to assess diabetes is also recommended. Finally, screening for autoimmune connective tissue disease may be considered, especially in patients with suspicious symptoms such as joint pain, sikka syndrome, or photosensitivity [1,11]. Patients with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis who are left untreated and left for long periods of time have a high risk of developing spleen atrophy. The peripheral blood smear should be examined in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis with symptomatic celiac disease to evaluate the presence of Howell-Jolly bodies (basophilic debris in the erythrocytes), which indicates significant spleen atrophy. These findings indicate the need for evaluation of spleen function and appropriate immunization of covert organisms (eg pneumococcal vaccine) [11,13,14].

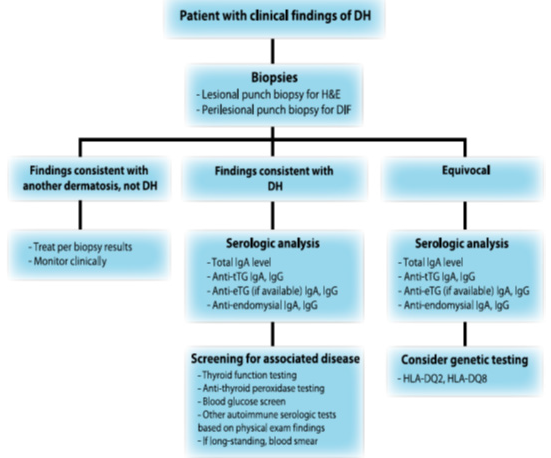

From the explanation above, it can be compiled the flow of diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis as follows: If a patient is suspected of having dermatitis herpetiformis, a basic history and basic clinical examination is found first. If there are signs that suggest a possible diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis, the first additional examination is needed, namely biopsy of the lesion and perilession. If the biopsy results are inconsistent with dermatitis herpetiformis and lead to other dermatoses, then therapy is given according to the other established diagnosis [6,8].

If the biopsy results are consistent with dermatitis herpetiformis, it is recommended to carry out a serological examination to determine the total levels of IgA, anti-tTG IgA IgG, anti-eTG IgA IgG, and anti-endomycial IgA IgG then followed by additional examinations for other disorders that may arise along with dermatitis herpetiformis, such as thyroid function tests, blood sugar screening, peripheral blood smears, and so on. If the results of equivocal dermatitis herpetiformis, it is advisable to carry out a serological examination to determine the total levels of IgA, antitTG IgA IgG, anti-eTG IgA IgG, and anti-endomisial IgA IgG then consider whether additional genetic testing is needed to determine the presence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA- DQ [13,14]. The flow of this examination is summarized in Figure 4 as follows:

Management and Treatment

Gluten Free Diet

The main therapeutic management of dermatitis herpetiformis is a gluten-free diet. Adherence to a strict gluten-free diet resulted in resolution of symptoms of dermatitis herpetiformis and a positive development of intestinal pathology. Despite implementing a non-strict gluten-free diet, the accumulation of IgA in the dermoepidermal junction in dermatitis herpetiformis patients will slowly disappear and may take several years to completely disappear. The gluten challenge in dermatitis herpetiformis patients will cause the re-emergence of IgA accumulation on the skin and flaring as a clinical skin symptom in dermatitis herpetiformis. In rare patients, the application of a gluten-free diet does not promote a healing process in these patients. This indicates that there may be other processes involved in the pathogenesis of the disease [10,11,14,15].

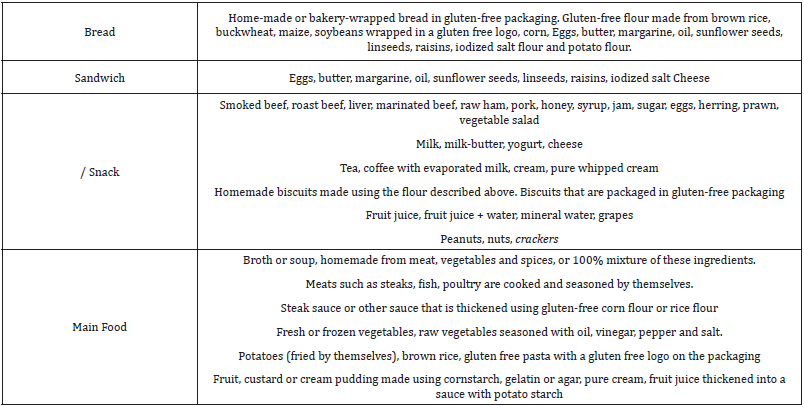

Consultation with a nutritionist can be recommended because maintaining patients on a gluten free diet can be difficult and requires a great deal of commitment on the part of the patient to live it. Some examples of what product groups and products can be consumed by people with dermatitis herpetiformis on a glutenfree diet can be seen in Table 1. Products containing gluten are made from cereals, including wheat, barley, and rye. In addition, some dietary additives that can be found in vitamin supplements or gluten free foods may contain gluten derivatives and should and should be removed from those on a gluten free diet. Some authors recommend avoiding oats because some oat-based products are contaminated with gluten-containing cereals [9,11,16] (Table 1).

Table 1: Group of products and products that are allowed to be consumed by patients on a gluten-free diet [9].

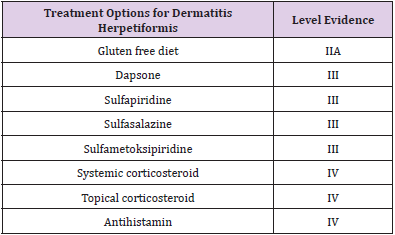

However, several studies have shown that patients with dermatitis herpetiformis can consume pure, unprocessed oats, thereby reducing the risk of developing skin symptoms in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. The advantages of a gluten-free diet are many. In addition to relieving the clinical symptoms of gluten sensitivity, a gluten-free diet reduces the malabsorption associated with gluten intolerance, which allows the patient to lead a healthy lifestyle and eliminates the increased appearance of lymphoma induced by chronic antigen stimulation in dermatitis herpetiformis patients. Whether a gluten-free diet plays a role in the development of other autoimmune diseases in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis, this needs further investigation [11,13,14] (Table 2).

Dapsone

Dapsone has both anti-inflammatory and antibacterial functions and inhibits the emergence of neutrophils and tissue injury mediated by local neutrophils and eosinophils. Supposedly, the skin manifestations and symptoms of dermatitis herpetiformis should disappear within a few days of receiving dapsone therapy. Doses of 25 to 100 mg per day are usually sufficient for symptom control [1,11]. In other sources, dapsone can be given up to a dose of 400 mg per day. Unfortunately, dapsone therapy alone cannot suppress gastrointestinal symptoms caused by gluten sensitivity, nor does it reduce the risk of conditions associated with dermatitis herpetiformis. Therefore, pharmacological therapy can be considered as an adjunct therapy in dermatitis herpetiformis patients who are on a gluten-free diet. A combined gluten-free and dapsone-free diet regimen is usually recommended at the time of diagnosis. Patients on a gluten-free diet can usually discontinue dapsone therapy within the next few months and may need to return to control the onset of symptoms [12-14].

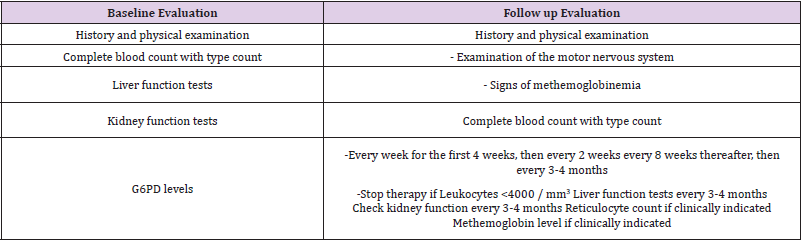

Dapsone is usually well tolerated. Some of the prominent side effects include side effects on hematology, namely methemoglobinemia which is the most common side effect. Concomitant therapy with cimetidine or vitamin E can reduce the symptoms associated with mild methemoglobinemia. The haematological side effects of dapsone are mediated via the metabolic product hydorkillamine, which can induce hemolysis and, although rare, can cause agranulocytosis [10,17,18]. Patients suffering from G6PD deficiency may be more susceptible to dapsone therapy, namely hemolysis. And may need to receive smaller amounts of dapsone therapy and require a more frequent follow-up. Agranulocytosis is a rare side effect of dapsone, and the mechanism by which this side effect occurs is still unknown. Another side effect of dapsone is a systemic hypersensitivity syndrome to drugs that often occurs with certain antiepileptic drugs. This serious complication requires discontinuation of therapy and receiving systemic corticosteroid therapy [1,13]. Patients receiving dapsone therapy should undergo routine follow-up, as shown in Table 3, in the form of a complete blood count, especially in the first 3 months of therapy.

In other literature, the authors found that Dapsone can be used as a test therapy for diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis. Administration of Dapsone 100-200 mg per day in adults who respond with improvement in symptoms of skin lesions within 48- 72 hours in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis is considered a positive therapeutic test for patients with dermatitis herpetiformis [9,12,13].

Other Sulphon Drugs

Apart from dapsone, the use of sulfasalazine and sulfametoksipiridazine is also reported to be used in the management of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. This is because the metabolism of the two drugs against sulphapyridine has a similar action to the metabolism of dapsone. Because sulfasalazine is absorbed variably, the outcome of therapy is more difficult to predict; it is therefore positioned as a second-line treatment agent for dermatitis herpetiformis. Usually, controlled patients are given sulphapiridine at a dose of 1 to 2 g orally per day. As for sulfasalazine, it was reported that the patient responded at a dose of 2 to 4 g per day [10,11]. And in other literature, the authors found that the recommended therapy for dermatitis herpetiformis in order to achieve fast and lasting results for sufferers is to provide a gluten-free diet directly in combination with Dapsone (100 - 200 mg per day for adults) and sulfapiridine (1 - 1.5 g per day for adults) [11,14].

Corticossteroids

Systemic corticosteroids are generally ineffective for the treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. However, the use of potent and superpotent topical steroids such as clobetasol propionate has a role in reducing local pruritus. Topical steroids should not be used alone in the treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis but should be used together with systemic steroids as described above, and only in the acute phase of dermatitis herpetiformis [1,10,11].

Antihistamin

Antihistamines have a limited role as adjunct therapy to control pruritus associated with dermatitis herpetiformis because their efficacy is not very high. When administered, it is advisable to use third generation antihistamines with specific activity on eosinophil granulocytes [1,10].

Other Pharmacological Treatment

In uncontrolled studies and several case reports, cyclosporine, colchicine, heparin, tetracyclines, and nicotinamide are claimed to be quite effective in therapy in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. But still requires further study and research [11].

Prognosis

The management of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis should be a team consisting of a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist and a nutritionist. Patients require follow-up to monitor longterm medication use and control recurrence of symptoms. Regular visits will facilitate screening and early detection of autoimmune conditions or neoplasms that may be associated with dermatitis herpetiformis and to obtain referral therapy for patients experiencing them. Laboratory tests (e.g. complete blood count to determine whether nutritional deficiencies are present) can be indicated at regular intervals for symptomatic patients and mandatory for those undergoing systemic therapy. Counseling regarding family screening should be recommended once the diagnosis has been made. Several sources of information are available to patients and their families, including educational workshops and free screening for celiac disease. Given the increasing number of cases inherited from dermatitis herpetiformis, close monitoring of the first-degree relations of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis would be very useful [1,2,7,10,11].

Patients on a strict gluten-free diet recover well. One study stated that only 15% of patients on a gluten-free diet continued to need a stable dose of dapsone, while the rest were able to stop or decrease the daily dose to 50% or less. Serum IgA antibodies to tTG and eTG may be useful in monitoring. Although some studies show a possible protective effect of implementing a gluten-free diet against intestinal lymphoma, it is unclear whether a gluten-free diet also influences the development of other autoimmune diseases. The overall odds of survival for the next 10 to 15 years in dermatitis herpetiformis do not differ from the average population [1,3,11].

Conclusion

The management of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis should be a team consisting of a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist and a nutritionist. Patients require follow-up to monitor long-term medication use and control recurrence of symptoms. Regular visits will facilitate screening and early detection of autoimmune conditions or neoplasms that may be associated with dermatitis herpetiformis and to obtain referral therapy for patients experiencing them.

References

- Ronaghy A, Katz SI, Hall RP (2012) Dermatitis herpetiformis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AM, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill Medical p. 1199-1211.

- Reunala TL (2001) Dermatitis herpetiformis. Clinics in Dermatology 19(6): 728-736.

- Antiga E, Caproni M, Fabbri P (2012) Dermatitis herpetiformis: novel advances and hypotheses. World J Dermatol 1(3): 24-29.

- Karpati S (2012) Dermatitis herpetiformis. Clinics in Dermatology 30(1): 56-59.

- Prasant J (2014) A review on dermatitis herpetiformis. International Journal of Pharma and Review 3(3): 72-78.

- Bonciani D, Verdelli A, Bonciolini V, D’Errico A, Antiga E, et al. (2012) Review article: dermatitis herpetiformis: from the genetics to the development of skin lesions. Clinical and Developmental Immunology 12: 239691.

- Caproni M, Antiga E, Melani L (2009) Review article: guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Journal European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 23: 633-638.

- Bolotin D, Rosic VP (2011) Dermatitis herpetiformis: Part I Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol 64(6): 1017-1024.

- Zone JJ (2005) Skin manifestations of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 128(4): 87-91.

- Anwar MI, Rashid A, Tahir M, Ijaz A (2013) Review article: Guidelines for the management of dermatitis herpetiformis. Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists 23(4): 428-435.

- Bolotin D, Rosic VP (2011) Dermatitis herpetiformis: Part II Diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 64(6): 1027-1033.

- Fabbri P, Caproni M (2005) Dermatitis herpetiformis. Orphanet Encyclopedia.

- Kotze LM (2014) Review: dermatitis herpetiformis, the celiac disease of the skin. Arquivos de Gastroenterologia.

- Bonciolini V, Bonciani D, Verdelli A, D’Errico A, Antiga E, et al. (2012) Review article: newly described clinical and immunopathological feature of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clinical and Developmental Immunology.

- Cardones AR, Hall RP (2011) Management of dermatitis herpetiformis. Dermatol Clin 32(2): 275-281.

Review Article

Review Article