ABSTRACT

Introduction: Hypertension is a major chronic lifestyle disease and important public health problem worldwide. A recent report indicates that nearly one billion adults had hypertension in 2000 and this is predicted to increase to 1.56 billion by 2025.

Methods: A retrospective cross-sectional study was used.

Result: This study was conducted for prevalence of hypertension, and its risk factors among doctors in AL-Thawra hospital in Sana’a in 2019. The prevalence of hypertension in this study was found to be 13%.

Conclusion: knowledge and awareness regarding the health consequences of lifestyle changes are generally expected to be high among clinicians. This in turn could influence the prevalence of lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and hypertension among them.

Keywords: Hypertension; Sana’a; Hypertension among Doctors

Abbreviations: ABI: Ankle-Brachial Index; ABPM: Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring; ACE: Angiotensin- Converting Enzyme; ACEi: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor; ACR: Albumin Creatinine Ratio; AF: Atrial Fibrillation; ARB: Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; AV: Atrioventricular; BMI: Body Mass Index; BP: Blood Pressure; CCB: Calcium Channel Blocker; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; CK-MB: Creatinine Kinase-Muscle/Brain; CMR: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CT: Computed Tomography; CV: Cardiovascular; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure; ECG: Electrocardiogram; eGFR: Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; ELSA: European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis; ENaC: Epithelial Sodium Channel; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; HBPM: Home Blood Pressure Monitoring

Introduction

Hypertension is a major chronic lifestyle disease and important public health problem worldwide. A recent report indicates that nearly one billion adults had hypertension in 2000 and this is predicted to increase to 1.56 billion by 2025 [1]. Hypertension is a precursor to major diseases like CVD and renal failure etc. High BP is estimated to cause 7.1 million deaths and annually accounting for 13% of all deaths globally. In the developing countries the mortality and morbidity of CVD are on the rise [2].Hypertension and obesity are very strongly associated with cardiovascular diseases all over the world. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the first cause of death globally, killing about 17.5 million people annually, representing 30% of all global deaths. Projections suggest that by 2013, over 23 million people would die of CVDs annually [3].

The Problem Statement

Doctors play a vital role in the health and welfare of the people of a nation. Health of the doctors is of importance because they themselves must be healthy to perform their jobs optimally under challenging work environments. Many of the previous studies reported that, doctors who have healthy behaviors or received some preventive practices, were more likely to counsel their patients to have similar health-promoting behaviors. Doctors’ health, including Physical and mental health issues, is very important where their health affects their patients [4]. Knowledge and awareness regarding CVDs and the associated risk factors is expected to be good among doctors and nurses since they have access to information. However, they are also known to have a sedentary lifestyle with high levels of stress, lack of proper rest and irregular eating habits making them highly vulnerable to Cardio-vascular diseases [5-7]. Though there are multiple studies that have looked at the prevalence of hypertension risk factors in the general population, there are only few studies looking at the prevalence of risk factors for hypertension among the doctors in Yemen or abroad. The prevalence of risk factors for hypertension among the doctors in a tertiary care hospital will help in designing necessary interventions for the prevention of hypertension among them. Hence, I aim from this study to quantify the prevalence of hypertension and the hypertension risk factors among doctors in tertiary care medical college hospitals in Sana’a city.

Justification

a) I hope from this research to be a guide for the health system and help health administrators in surveillance and monitoring the disease and contributes to drawing up the policy strategy for health services on this matter especially in the absence and a little reliable information in this scope.

b) This research provides information for health workers, students of health and interested readers about the determinants and risk factors which contribute to occurrence of hypertension among medical doctors.

Research Questions

This study specially aims to answer the following questions:

a) How is the prevalence of hypertension among medical doctors in Yemen in 2018?

b) What are the factors and determinants affecting the prevalence of hypertension among medical doctors in Yemen?

Objective of the Study

General Objective: To determine the prevalence of hypertension among doctors and risk factors affecting it.

Specific Objective The study undertakes to:

a) Determining the prevalence of hypertension among doctors in Yemen,

b) Identifying certain risk factors among doctors and

c) Assessing the preventive methods adopted.

Hypothesis

a) The prevalence of hypertension among medical doctors in Yemen is 10%.

b) The hypertension is statistically significant associated with following risk factors, age, BMI, smoking, Qat chewing, marital status, occupational period by years and non-statistically significant with sex, family history, associated disease(DM-II) , monthly income and hours of work daily.

Literature Review

This chapter reviews the relevant literature from previous studies on patients. The conceptual, as well as the theoretical frameworks will be described.

Definition, Classification, and Epidemiological Aspects of Hypertension

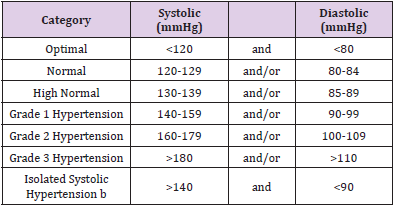

Definition of Hypertension: The relationship between BP and cardiovascular (CV) and renal events is continuous, making the distinction between non-hypertension and hypertension, based on cut- off BP values, somewhat arbitrary [8-10]. However, in practice, cut-off BP values are used for pragmatic reasons to simplify the diagnosis and decisions about treatment. Epidemiological associations between BP and CV risk extend from very low levels of BP [i.e. systolic BP (SBP) >115mmHg]. However, ‘hypertension’ is defined as the level of BP at which the benefits of treatment (either with lifestyle interventions or drugs) unequivocally outweigh the risks of treatment, as documented by clinical trials. This evidence has been reviewed and provides the basis for the recommendation that the classification of BP and definition of hypertension remain unchanged from previous ESH/ESC Guidelines (Table 1) [8]. Hypertension is defined as office SBP values >_140mmHg and/or Diastolic BP (DBP) values >_90mmHg. This is based on evidence from multiple RCTs that treatment of patients with these BP values is beneficial.

Classification of Blood Pressure: It is recommended that BP be classified as optimal, normal, high–normal, or grades 1-3 hypertension, according to office BP [8].

Prevalence of Hypertension: Based on office BP, the global prevalence of hypertension was estimated to be 1.13billion in 2015 [11-14], with a prevalence of over 150million in central and eastern Europe. The overall prevalence of hypertension in adults is around 30%-45% [15], with a global age standardized prevalence of 24% and 20% in men and women, respectively, in 2015 [11]. This high prevalence of hypertension is consistent across the world, irrespective of income status, i.e. in lower, middle, and higher income countries [15]. Hypertension becomes progressively more common with advancing age, with a prevalence of >60% in people aged >60 years [15,16]. As populations age, adopt more sedentary lifestyles, and increase their body weight, the prevalence of hypertension worldwide will continue to rise. It is estimated that the number of people with hypertension will increase by 15% 20% by 2025, reaching close to 1.5 billion [17].

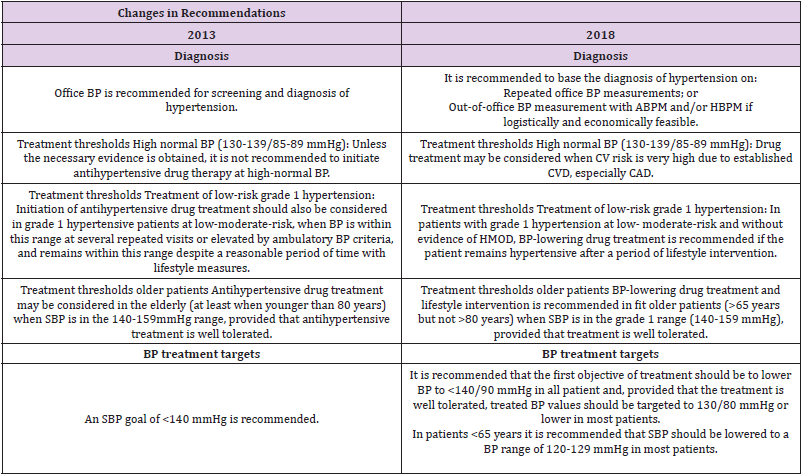

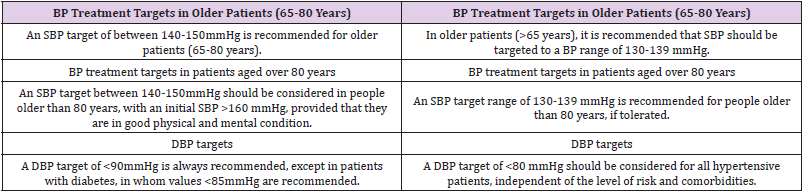

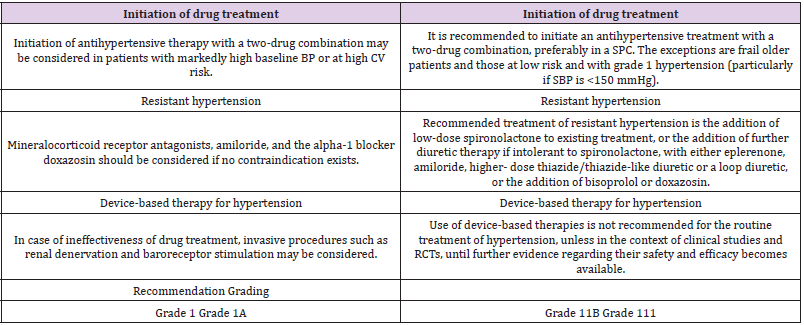

Table 1: Classification of office blood pressure and definitions of hypertension grade. Changes in Recommendations between 2013 and 2018.

Blood Pressure Measurement Conventional Office Blood Pressure Measurement

Auscultatory or oscillometric semi-automatic or automatic sphygmomanometers are the preferred method for measuring BP in the doctor’s office. These devices should be validated according to standardized conditions and protocols [8]. BP should initially be measured in both upper arms, using an appropriate cuff size for the arm-circumference. (Thiazides and thiazide-like diuretics such as chlortalidone and indapamide), based on:

a) Proven ability to reduce BP.

b) Evidence from placebo-controlled studies that they reduce CV events; and

c) Evidence of broad equivalence on overall CV morbidity and mortality, with the conclusion that benefit from their use predominantly derives from BP lowering [8].

Blockers of the Renin-Angiotensin System (Angiotensin- Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers)

Both ACE inhibitors and ARBs are among the most widely used classes of antihypertensive drugs. They have similar effectiveness [18-26], as each other and other major drug classes on major CV events and mortality outcomes [9]. ARBs are associated with significantly lower treatment discontinuation rates for adverse events than those of all other antihypertensive therapies [27], and similar rates to placebo [24]. ACE inhibitors and ARBs should not be combined for the treatment of hypertension because there is no added benefit on outcomes and an excess of renal adverse events [28,29]. Both ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce albuminuria more than other BP-lowering drugs and are effective at delaying the progression of diabetic and non- diabetic CKD [8].

Calcium Channel Blockers

CCBs are widely used for the treatment of hypertension and have similar effectiveness as other major drug classes on BP, major CV events, and mortality outcomes.2,292CCBs have a greater effect on stroke reduction than expected for the BP reduction achieved but may also be less effective at preventing HFrEF [8].

Thiazide/Thiazide-Like Diuretics

Diuretics have remained the cornerstone of antihypertensive treatment since their introduction in the 1960s. Their effectiveness in preventing all types of CV morbidities and mortality has been confirmed in RCTs and meta-analyses.300 Diuretics also appear to be more effective than other drug classes in preventing heart failure [8].

Beta-Blockers

RCTs and meta-analyses demonstrate that when compared with placebo, beta-blockers significantly reduce the risk of stroke, heart failure, and major CV events in hypertensive patients.

Hypertension in Specific Circumstances

Resistant Hypertension: Hypertension is defined as resistant to treatment when the recommended treatment strategy fails to lower office SBP and DBP values to <140mmHg and/or<90mmHg, respectively, and the inadequate control of BP is confirmed by ABPM or HBPM in patients whose adherence to therapy has been confirmed. The recommended treatment strategy should include appropriate lifestyle measures and treatment with optimal or besttolerated doses of three or more drugs, which should include a diuretic, typically, an ACE inhibitor or an ARB, and a CCB. Pseudoresistant hypertension and secondary causes of hypertension should also have been excluded [8].

Masked Hypertension: Masked hypertension is defined in people whose BP is normal in the office but elevated on out-of-office BP measurements. Such people usually have dysmetabolic risk factors and asymptomatic organ damage, which are substantially more frequent than in people who are truly normotensive [8].

Hypertension and Pregnancy: Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy affect 5-10% of pregnancies worldwide and remain a major cause of maternal, foetal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Maternal risks include placental abruption, stroke, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The foetus is at high risk of intrauterine growth retardation (25% of cases of pre-eclampsia), prematurity (27% of cases of preeclampsia), and intrauterine death (4% of cases of pre- eclampsia) [8].

Oral Anticoagulants and Hypertension: Many patients requiring oral anticoagulants (e.g. with AF) will be hypertensive. Hypertension is not a contraindication to oral anticoagulant use. However, although its role has been unappreciated in most old and more recent RCTs on anticoagulant treatment [8], hypertension does substantially increase the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage when oral anticoagulants are used, and efforts should be directed towards achieving a BP goal of <130/80mmHg in patients receiving oral anticoagulants. Detailed information on hypertension and oral anticoagulants has been published recently [8]. Anticoagulants should be used to reduce the risk of stroke in most AF patients with hypertension, including those with AF in whom hypertension is the single additional stroke risk factor [8]. BP control is important to minimize the risks of AF-related stroke and oral anticoagulantrelated bleeding. Until more data are available, BP values in AF patients taking oral anticoagulants should be at least <140mmHg for SBP and <90mmHg for DBP. Oral anticoagulants should be used with caution in patients with persistent uncontrolled hypertension (SBP >_180mmHg and/or DBP >_100mmHg), and urgent efforts to control BP should be made.

White-Coat Hypertension and Masked Hypertension

White-coat hypertension refers to the untreated condition in which BP is elevated in the office, but is normal when measured by ABPM, HBPM, or both [30]. Conversely, ‘masked hypertension’ refers to untreated patients in whom the BP is normal in the office but is elevated when measured by HBPM or ABPM [31]. The term ‘true normotension’ is used when both office and out-of-office BP measurements are normal, and ‘sustained hypertension’ is used when both are abnormal. In white-coat hypertension, the difference between the higher office and the lower out-of-office BP is referred to as the ‘white-coat effect’ and is believed to mainly reflect the pressor response to an alerting reaction elicited by office BP measurements by a doctor or a nurse,82 although other factors are probably also involved [32].

Hypertension and Disease

Hypertension and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Hypertension is the most frequent comorbidity in patients with COPD, and coincidence of the two diseases may affect 2.5% of the adult population [33]. Patients with hypertension and COPD are at particularly high CV risk [33,34]. Both conditions share similar environmental risks and, in addition, hypoxia may exacerbate risk [33,35]. Treatment of COPD with anticholinergic agents and longacting beta-2 adrenoceptor agonists may adversely affect the CV system (increase heart rate and BP). The presence of COPD also has an impact on the selection of antihypertensive drugs, which should consider their effects on pulmonary function. Concern has been predominantly directed to the use of beta-blockers, although there is evidence that in COPD these drugs maintain their CV-protective effects [35,36]. Beta-blockers may negatively affect the reduced basal lung function in patients with COPD, diminish the effectiveness of emergency beta-agonist administration, reduce the benefit of long acting beta-agonist treatment, and make the discrimination of asthma and COPD more difficult. That said, when tolerated, the use of cardiac beta1-selective beta-blockers in patients with COPD has proven to be safe in different settings, including hypertension [35]. It should also be noted that diuretics may decrease the plasma level of potassium (in addition to the hypokalaemic effects of glucocorticoids and beta2-adrenoceptor agonists), worsen carbon dioxide retention (including metabolic alkalosis- related hypoxia in hypoventilated patients), increase haematocrit, and deteriorate mucus secretion in bronchi. Therefore, in general, diuretics are not recommended for widespread use in hypertensive patients with COPD [33,37]. In conclusion, management of hypertensive patients with COPD should include lifestyle changes, among which cessation of smoking is essential. CCBs, ARBs or ACEIs, or the CCB/RAS blocker combination are recommended as the initial drugs of choice. If the BP response is poor, or depending on other comorbidities, thiazides or thiazide-like diuretics and beta1-selective beta-blockers can be considered.

Hypertension and Heart Disease (Coronary Artery Disease): There are strong epidemiological relationships between CAD and hypertension. The Inter heart study showed that 50% of the population-attributable risk of a myocardial infarction can be accounted for by lipids, with hypertension accounting for 25% [14,38]. Another registry-based study of over 1million patients showed that ischaemic heart disease (angina and myocardial infarction) accounted for most (43%) of the CVD-free years of life lost due to hypertension from the age of 30 years [12]. More compelling is the beneficial effect of BP treatment on reducing the risk of myocardial infarction. A recent meta-analysis of RCTs of antihypertensive therapy showed that for every 10mmHg reduction in SBP, CAD was reduced by 17% [9]. A similar risk reduction has been reported by others with more intensive BP control. 496 The benefits of reducing cardiac events are also evident in high-risk groups, such as those with diabetes [8]. There remains some inconsistency over the optimal BP target in hypertensive patients with overt CAD, and especially whether there is a J-curve relationship between achieved BP and CV outcomes in CAD [8]. A recent analysis 501 of 22672 patients with stable CAD who were treated for hypertension found that, after a median follow-up of 5.0years, an SBP of >_140mmHg and a DBP of >_80mmHg were each associated with increased risk of CV events. An SBP of <120mmHg was also associated with increased risk, as was a DBP of <70mmHg. Similar findings were also reported from another analysis of RCT data evaluating the relationships between achieved BP and risks of CV outcomes. Whether a J-curve phenomenon exists in patients with CAD who have been revascularized remains uncertain. Other analyses do not support the existence of a J-curve, even in hypertensive patients at increased CV risk [8,39]. For example, in patients with CAD and initially free from congestive heart failure enrolled in On target, a BP reduction from baseline over the examined BP range had little effect on the risk of myocardial infarction and predicted a lower risk of stroke.8 Thus, a target BP of approximately <130/80mmHg in patients with CAD appears safe and can be recommended but achieving a BP <120/80mmHg is not recommended. In hypertensive patients with CAD, beta blockers and RAS blockers may improve outcomes post-myocardial infarction [8]. In patients with symptomatic angina, beta-blockers and calcium antagonists are the preferred components of the drug treatment strategy [40-42].

Hypertension and Chronic Kidney Disease

Hypertension is a major risk factor for the development and progression of CKD, irrespective of the cause of CKD. In patients with CKD, resistant hypertension, masked hypertension, and elevated nighttime BP are common, and are associated with a lower eGFR, higher levels of albuminuria, and HMOD [8].

Hypertension in Valvular Disease and Aortopathy- Coarctation of the Aorta: When feasible, treatment of aortic coarctation is predominantly surgical and usually done in childhood. Even after surgical correction, these patients may develop systolic hypertension at a young age and require long-term follow- up. Few patients with aortic coarctation remain undetected until adult life, and by then often have severe hypertension, HMOD (especially LVH and LV dysfunction), and an extensive collateral circulation below the coarctation. Such patients should be evaluated in a specialist center.

Methodology

Background for Study Place

Location: Yemen is located in south-western of Asia regionally it follows Middle East Region. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia from north, Oman from east, Arab Sea from south and Red Sea from west. Area is 527968 (square kilometer) with population density 47/square kilometer. Population and distribution; about 24 million people, distributed in 22 governorates and 333 districts. Rural population forms 30% of total whereas urban population forms 70%. Sana’a is the capital of Yemen.

Economic and Security Situation: Yemen is ranked out 132 globally in development. Also Yemen suffers from many challenges and security crisis especially after 2011.

Study Design

This study is a Cross-sectional among doctors working in ALThawra Teaching and General Hospital at Sana’a.

Methods And Tools

Study Population: We carried out this cross sectional study among the doctors working in AL Thawra Teaching and General Hospital at Sana’a. The study was carried out for 3 months from Dec 2018 to Feb 2019 . Out of 135 physicians, thousand physicians were selected randomly. A standardized questionnaire was used for the physicians. The participants underwent anthropometric measurement blood pressure and answered the questionnaire. The physicians were screened by taking two blood pressure measurements at an interval of 2 minutes averages of readings were considered.

Sample Size: The sample size was calculated − with an anticipated prevalence of hypertension of 10%. According to Kish, L. (1965, 1995)38 the sample size for a simple random sample without replacement is as follows: N=(z/m)2 * p(1-p). so that n= (1.96/0.05)2 * 0.1(1- 0.1) = 135. Where my selected factors are Z=1.96 for 95% confidence level, M =0.05 margin of error (alpha) and P=10 % is the estimated value for the proportion of a sample that will respond a given way to a survey questions.

Sampling Frame: Is the list of doctors working at the hospital from which the sample size was selected using the probability simple random sampling?

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Standard diagnostic criteria based on JNC VII 39 and WHO 40 criteria. A person will be considered hypertensive if Systolic BP ≥140 mm of Hg and/or Diastolic BP ≥90 mm of Hg and persons already on hypertensive treatment. Any cases are incomplete in their data will be excluded. Person who were hypotensive, were excluded.

Data Collection: The participants were submitted for anthropometric measurement; blood pressure, body mass index and answer the questionnaire. The doctors will be screened by taking tow blood pressure measurements at an interval of 2 minutes and calculating the average for the tow readings will be considered. BMI( body mass index) will be calculated by BMI = weight (kg) / height (m)2 according to WHO recommendations (report on diabetes, 1999), where Overweight was defined as BMI between 25.00 and 29.99 kg/m2, and obesity as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m square [41].

Data Analysis: The collected data was coded and entered into SPSS version 21 package. The chi square test will be used to compare between hypertensive and non- hypertensive cases. For categorical risk factors, T-test was used to compare the mean of age as a continuous risk factors with the outcome.

Study Variables

Gender, age, family history, BMI, smoking, Qat chewing, monthly income, marital status, occupational years, associated disease(DMII) and hours of work daily.

Definition of Variables

Independent Variables

a) Age (27-38years, more than 38 years)

b) Sex (male, female).

c) Smoking (yes/no).

d) Qat chewing (yes/no)

e) Family history (yes/no)

f) BMI (normal less than 25 kg/m2 / overweight/obese ≥ 25 kg/ m2)

g) Hours of work per day

h) Marital status ( Married/ Single)

i) Income per month( Five Hundred Or Less/ More Than Five Hundred).

j) Associated disease- DM-II (No/ Yes)

k) occupational period ( five years or less/ more than five years)

Dependent Variables: Dependent variable is blood pressure

(normal- less than 140/90 and hypertension ≥140/90)Ethical Considerations

Confidentiality of the respondents’ data had been respected. Data had been presented in its aggregate form to ensure confidentiality.

Result and Discussions

Result

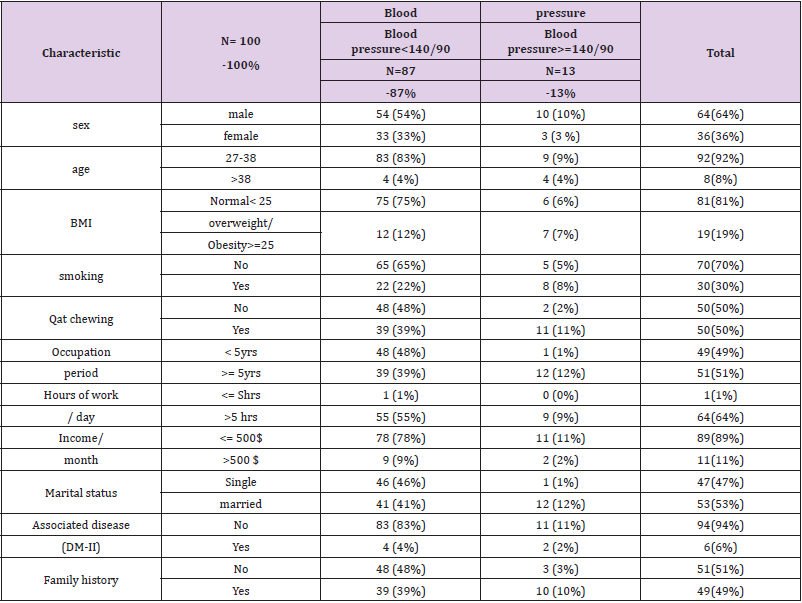

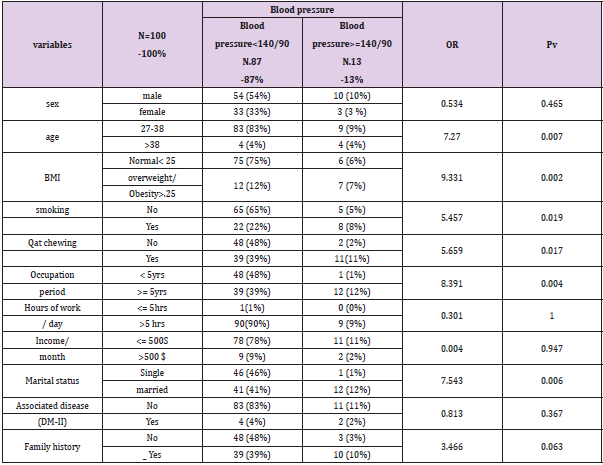

A total of 100 physicians were approached for the study, all responded to questionnaire, and also made themselves available for the physical measurements. Of the hundred responses, 36 (36%) were female, while 64 (64%) were male, and had an average age of 32.06 ± 9.62 years. Most of the physician’s 53 (53%) were married and 47 (47%) were single (Table 2). The prevalence of hypertension among the physicians was 13% (13 subject). Out of the total, 10 were males (10%) and 3 (3%) were females. The result was not statistically significant. Out of 100, physicians, 92(92%) their ages were between 27-38 years. Of them, physicians 9 (9%) were hypertensive and 8 physicians their ages more than 38 years old, of them 4 physicians were hypertensive. The result was statistically significant (PV =.007, OR=7.270) (Tables 3 & 4). Only 19 (19 %) of the physicians were overweight/obese, of them 7 physicians (7%) were hypertensive. Out of 81(81 %) who were normal weight, only 6(6 %) physicians were hypertensive. The result was statistically significant ( PV = .002, OR= 9.331). Out of the total subjects, 70 (70%) of the physicians were not smoking; of them 5(5%) were hypertensive. The smokers were 30 (30%) of them 8 (8%) physicians were hypertensive.

The result was statistically significant (PV = .019, OR= 5.456). Half (50%) of the subjects were Qat chewing; of them (11%) were hypertensive. This is higher percentage than non- Qat chewing (2%) physicians. This association between hypertension and Qat chewing was statistically significant ( PV = .0017, OR= 5.659). The highest percentage (12%) of hypertensive subjects came from among the subjects who had been in employment more than 5 years, while the least percentage ( 1%) of hypertensive subjects was seen among subjects with occupation period less than 5 years. This association was statistically significant (PV = .004, OR= 8.391). Out of the total subjects, the highest percentage (11%) of hypertensive physicians among whose monthly income less than 500$ comparing to (2%) of hypertensive physicians whose income more than 500$ monthly. This result was not statistically significant. More than half 53 (53%) of the subjects were married; of them 12(12%) were hypertensive comparing 1(1%) of hypertensive subject in group singles who were 47 (47%) of subjects. This association was statistically significant ( PV= .006, OR= 7.543). The highest percentage (94%) of subjects were not associated with DM-II of them 11(11%) were hypertensive. This result was not statistically significant. A positive family history of hypertension was not statistically associated with a higher prevalence of hypertension (Tables 5 & 6).

Table 5: Characteristics of subjects with comparison of hypertensive with non-hypertensive in AL-Thawra hospital at Sana’a in 2019.

Discussion

This study was conducted for prevalence of hypertension, and its risk factors among doctors in AL-Thawra hospital in Sana’a. The prevalence of hypertension in this study was found to be 13% . A Saudi Arabian study in 2013 revealed that the prevalence of hypertension was 28% among the health professionals. According to a study done by Abhishek Ghosh, et Al 42 among Doctors of different specialties in a tertiary-care teaching hospital in Eastern India, where 14.82% of the doctors showed hypertension (2015). The prevalence of hypertension was higher among the male subjects (10%) than among the female subjects(3%). Male to female ratio of hypertension is approximately 2:1. Several studies support the finding that indicates that males were more likely to be hypertensive than females [43,44]. There is a significant association between the prevalence of hypertension and advancing age (P <0.05) in this study. Most other studies world-wide have also shown that the prevalence of hypertension increases with advancing age [43,45]. Smoking increases the risks of hypertension as there is significant association (PV < 0.05) in this study. Other studies however have reported a relationship between smoking and hypertension [46].

Also, this study revealed there is strong correlation between Qat as a risk factor and hypertension (PV< 0.05). However this association is interacted with effect of smoking where qat chewing in Yemen usually accompany with smoking. In this study also found that of subjects were overweight or obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) where there is strong association between hypertension and BMI (PV < 0.05). This percentage 19% is lower than many of studies. According to Mohan, et al. [47-49]. among elderly population, age, BMI and smoking were strongly associated with hypertension. The highest prevalence of hypertension (12%) was seen among the subjects who had occupation period more than 5 years. The association between the occupation period and increased prevalence of hypertension has previously been documented by Landsbergis et al 48. This finding is possibly due to the cumulative effect of exposure to high job strain resulting subsequently in the increase in hypertension prevalence. It may also be as a result of age-related effect of hypertension.

Study Limitations

The study has some limitations. First, self‑report bias and recall bias will have affected the validity of responses. Second, the study did not record the duration and quantity of tobacco and Qat consumption. Third, the small sample size maybe not enough to give more significant result. Also this study conducted under difficult circumstances in the country with unstable social conditions where the security situation is most disturbance and totally amputation of salary for employees. These factors without doubt affect the outcome.

Conclusion

Finally, since there a few studies in these contexts, future research with a big sample size should be carried out to explore the double burden of hypertension. Practicing physicians involved in clinical care have good access to information on disease frequency and determinants. Therefore, knowledge and awareness regarding the health consequences of lifestyle changes are generally expected to be high among clinicians. This in turn could influence the prevalence of lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and hypertension among them.

Acknowledgment

First and foremost I feel always deeply indebted to ALLAH who helped me to achieve this research. I dedicate this research to my parents who implicated seeds of the success in myself and encouraged me to continue the medicine study until to reach the specialization degree in internal medicine. I would like to express my great thankful to my supervisor Professor Ahmad Kaed and to Pro. Yahya Alezzy, Prof. Yassin Abdalkadir, prof.Abdulhafid Alselwy and prof. Khalid saeed who kindly supervisd and motivated me to performance this research, thanks for their support, guidance and constant encouragement throughout this work. I would like to thank all my colleagues for helping me in preparation this research. I am greatly honored to express my sincere appreciation to all who contributed to this work for devoting their precious time to help me until complete this study.

References

- Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynoldsd K, Muntner P, Whaelton PK (2005) Global Burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 365(9455): 217-223.

- SR Nigudgi, Ajaykumar G, Tenglikar SG, Shrinivas Reddy B (2013) RGUHS J Med Sciences 3(1).

- Shailendra Kumar, B Hegde, Sathiyanarayanan S, Sanjana Venkateshwaran, Akshaya Sasankh (2015) Prevalence of Diabetes, Hypertension and Obesity among Doctors and Nurses in a Medical College Hospital in Tamil Nadu, India 2015. National Journal of Research in Community Medicine 4(3): 235-239.

- Kao LT, Chiu YL, Lin HC (2016) Prevalence of chronic diseases among physicians in Taiwan: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6: e009954.

- Kay MP, Mitchell GK, Del Mar CB (2004) Doctors do not adequately look after their own physical health. Med J Aust 181(7): 368-370.

- Richards JG (1999) The health and health practices of doctors and their families. NZ Med J 112(1084): 96-99.

- Sharma D, Vatsa M, Lakshmy R, Narang R, Bahl VK (2012) Study of cardiovascular risk factors among tertiary hospital employees and their families. Indian Heart J 64(4): 356-363.

- (2018) ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J.

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T (2106) Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 387(10022): 957-967.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (2002) Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 360(9349): 1903-1913.

- (2017) NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19.1 million participants. Lancet 389(10064): 37-55.

- Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, Pujades Rodriguez M, Shah AD, et al. (2014) Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet 383(9932): 1899-1911.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A (2014) Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 1. Overview, meta-analyses, and metaregression analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens 32(12): 2285-2295.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A (2004) INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 364(9438): 937-952.

- Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Gupta R, et al. (2013) Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 310(9): 959-968.

- (2003) European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 21(6): 1011-1053.

- Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK (2005) Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 365(9945): 217-223.

- Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Ukoumunne OC, Campbell JL (2012) Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379(9819): 905-914.

- Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, De Leeuw P, et al. (2008) European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens 26(8): 1505-1526.

- Hall JE, Do Carmo JM, Da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME (2015) Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res 116(6): 991-1006.

- Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM (2003) Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension 42(5): 878-884.

- Primatesta P, Falaschetti E, Gupta S, Marmot MG, Poulter NR (2001) Association between smoking and blood pressure: evidence from the health survey for England. Hypertension 37(2): 187-193.

- Doll R, Peto R, Wheatley K, Gray R, Sutherland I (199) Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 309(6959): 901-911.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A (2016) Effects of blood-pressure-lowering treatment in hypertension: 9. Discontinuations for adverse events attributed to different classes of antihypertensive drugs: meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens 34(10): 1921-1932.

- Volpe M, Mancia G, Trimarco B (2005) Angiotensin II receptor blockers and myocardial infarction: deeds and misdeeds. J Hypertens 23(12): 2113-2118.

- Reboldi G, Angeli F, Cavallini C, Gentile G, Mancia G (2008) Comparison between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and death: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens 26(7): 1282-1289.

- Kronish IM, Woodward M, Sergie Z, Ogedegbe G, Falzon L (2011) Metaanalysis: impact of drug class on adherence to antihypertensives. Circulation 123(15): 1611-1621.

- Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, et al. (2013) Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 369: 1892-1903.

- Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. (2008) Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 358(15): 1547-1559.

- Mancia G, Zanchetti A (1996) White-coat hypertension: misnomers, misconceptions and misunderstandings. What should we do next? J Hypertens 14(9): 1049-1052.

- Bobrie G, Clerson P, Menard J, Postel Vinay N, Chatellier G (2008) Masked hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens 26(9):1715-1725.

- Parati G, Omboni S, Staessen J, Thijs L, Fagard R (1998) Limitations of the difference between clinic and daytime blood pressure as a surrogate measure of the ‘white-coat’ effect. Syst-Eur investigators. J Hypertens 16(1): 23-29.

- Farsang CK, Kiss I, Tykarski A, Narkiewicz K (2016) Treatment of hypertension in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). European Society of Hypertension Scientific Newsletter 17: 62.

- Baker JG, Wilcox RG (2017) Beta-Blockers, heart disease and COPD: current controversies and uncertainties. Thorax 72: 271-276.

- Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE (2006) Meta-analysis: effect of long-acting beta-agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths. Ann Intern Med 144(12): 904-912.

- Rutten FH, Zuithoff NP, Hak E, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW (2010) Beta-blockers may reduce mortality and risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 170(10): 880-887.

- Coiro S, Girerd N, Rossignol P, Ferreira JP, Maggioni A (2017) Association of beta-blocker treatment with mortality following myocardial infarction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction: a propensity matched-cohort analysis from the High-Risk Myocardial Infarction Database Initiative. Eur J Heart Fail 19(2): 271-279.

- Kish L (1965) Survey sampling. New York: John Wiley & Sons

- (2003) The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevalence, detection, evaluation & treatment of high blood pressure. The JNC 7 report .JAMA 289(19): 2560-2572.

- (1996) WHO Expert Committee. Hypertension control. Geneva. WHO. Tech Rep. Ser.862. Geneva1996).

- (2008) World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva.

- Abhishek Ghosh, Keshab Mukhopadhyay, Rama Bera, Raju Dasgupta (2016) Prevalence of hypertension and prehypertension among doctors of different specialties in tertiary-care teaching hospital in Eastern India and its correlation with body mass index. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health 5(4): 709-713.

- Oghagbon EK, Okesina AB, Biliaminu SA (2008) Prevalence of hypertension and associate variables in paid workers in Ilorin, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 11(4): 342-346.

- Akinwumi Olayinka Owolabi, Mojisola Oluyemisi Owolabi , Akintayo David OlaOlorun, Isaac Olusayo Amole (2015) Hypertension prevalence and awareness among a health workforce in Nigeria. Internet Journal of Medical Update 10(2): 10-19.

- Franklin SS, Gustiti W, Wang ND (1997) Haemodynamic pattern of age-related changes in blood pressure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 96(1): 308-315.

- Desai MH, Kavishwar AA (2009) Study on effect of lifestyle risk factors on prevalence of hypertension among white collar job people of Surat. The Internet Journal of Occupational Health 1(1).

- Mohan V, Deepa M, Farooq S, Datta M, Deepa R (2007) Prevalence, Awareness and Control of Hypertension in Chennai - The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study. JAPI 55: 326-333.

- Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Pickering TG, Warren K (2003) Life-Course exposure to job strain and ambulatory blood pressure in men. Am J Epidemiol 157(11): 998-1006.

- Mitwalli AH, Harthi AA, Mitwalli H, Juwayed AA, Turaif NA (2013) Awareness, attitude, and distribution of high blood pressure among health professionals. J Saudi Heart Assoc 25(1): 19-24.

Research Article

Research Article