Abstract

Background: Since the advent of the Web and media, there has been a significant

change in the practice of Medicine. The physician is no longer the sole custodian of

medical knowledge. A substantial amount of consumer health-related information is

available on live streaming, other Internet sources and social media. Nearly two-thirds

of American adults (65%) use social networking sites, up from 7% when Pew Research

Center began systematically tracking social media usage in 2005. Pew Research reports

have documented in great detail how the rise of social media has affected such things

as work, politics and political deliberation, communications patterns around the globe,

as well as the way people get and share information about health [1]. Studies suggest

that consumer comprehension may be compromised if content exceeds what an average

American can easily understand. The average reading level in the United States is 8th

grade. The National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Health and Human

Services (USDHHS) recommend that patient education materials (PEM’s) be written at

or below the 6th grade level [2,3].

Objective: To determine the readability level of published materials likely to be

encountered by a patient following a Google search of the phrase “blood thinners”, a

popular synonym of anticoagulant.

Study Design: Analysis of Internet-based PEMs on anticoagulation therapy.

Methods: PEMs from the first 12 websites encountered on a Google search of the

phrase, “blood thinners,” were downloaded and assessed for readability using 9 different

indices: Flesch Reading Ease (FRE), Gunning Fog Index (GFI), Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level

(FKGL), Coleman-Liau Index (CLI), SMOG Formula (SMOG), Automated Readability Index

(ARI), Linsear Write Formula (LWF), Fry Readability Graph (FRG) and Raygor Estimate

Graph (REG). www.readabilityformulas.com was used to compute these readability

scores as well as an average grade level. Data were analyzed using the www.endmemo.

com.

Results: The average reading levels of the 12 PEM’s were between the 7th and 14th

grade with the overall average calculated between the 10th and 11th grade. The mean

readability and standard errors of mean are as follows: FRE 53.2 +/- 3.9, GFI 12.1 +/-

0.53, FKGL 10.2 +/- 0.67, CLI 10.8 +/- 0.49, SMOG 9.8 +/-0.51, ARI 10.3 +/- 0.63, LWF

11.4 +/- 0.74, FRG 10.8 +/- 0.57, REG 6.4 +/- 0.3 and average grade level10.5 +/- 0.57.

Conclusion: Our findings support that internet-based medical information on

anticoagulation therapy intended for consumer use is written well above USDHHS

recommended 6th-grade reading levels. Compliance with these recommendations may

increase the likelihood of consumer comprehension.

Introduction

Anticoagulants (blood thinners) are the mainstay

therapy for acute and long-term treatment and prevention of

numerous inheritable and acquired thrombo-embolic disorders

(antiphospholipid antibodies, Protein C deficiency, Chronic atrial

fibrillation, Deep venous thrombosis, Stroke, etc.). A study done

in 2007 by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

revealed that about 4.2 million Americans aged 18years or older had

at least one outpatient anticoagulant purchase. The study further

revealed that there were 27.9 million anticoagulant purchases and

$905.2 million was spent for outpatient anticoagulants in 2007 [4].

Internet based patient education materials (PEM) are playing an

increasingly prominent role in a patient’s understanding of disease

and the patient-physician relationship. Since the advent of the

Web, the practice of medicine has shifted significantly. No longer

is the physician sole gatekeeper of medical knowledge. Patients

have more and more recent medical information at their fingertips.

Internet proposes an easy-to-use, universal access to information

and provides various possibilities to find the latest up-to-date,

barrier free information that is independent of location and time.

Interactive services like online self-help-groups, chats with experts

and forums on special health topics can support active coping and

social support in a virtual community by anonymous contact. 71.7

percent of households reported accessing the Internet in 2011, up

from 18.0 percent in 1997 (the first year the Census Bureau asked

about Internet use) and 54.7 percent in 2003 [5].

The term “health literacy,” as described by the Joint Commission

(formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care

Organizations), refers to “the degree to which individuals have

the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health

information and services needed to make appropriate health

decisions.”2 The impact of literacy on health is significant. Adults

with low literacy skills have a poorer health status, 18 have average

health costs that are 6 times higher, 19 are less likely to comply

with medication regimens, and are less likely to understand their

illnesses. Reading level is an important component of health

literacy. The most recent large-scale national assessment of the

average reading level among Americans was performed by the

National Center for Education Statistics in 2003. It found that the

typical American reads between a 7th and 8th grade level [5,6]. The

United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS)

resolved that material is considered “easy to read” only if written

below a 6th-grade level. Material between the 7th and 9th grade levels

is viewed as “average difficulty,” and material above the 9th-grade

level is regarded as “difficult [7]. Readability is a measure of the

grade level necessary for an individual to adequately comprehend a

written document [8]. A number of objective scales have been used

throughout literature to calculate the readability of documents;

including the Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES), Flesch-Kincaid

Grade Level (FKGL), Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG),

Gunning Frequency of Gobbledygook (Gunning FOG), Raygor Graph

Grade Level, Coleman Liau Index, Automated Readability Index, and

the Linsear Write Formula.

Materials and Methods

In July 2016, the key phrase, “blood thinners,” was typed into

the Google search engine, and all of the websites that appeared

on the first page of results were opened. In all, there were 12

websites, each one having multiple articles/subsections, for a total

of 69 different hyperlinks related to anticoagulant therapy. The

69 WebPages were then subjected to analysis. The 12 websites

analyzed were as follows (in the order they appeared in the

Google search): Xarelto.com, Eliquis customer website, Pradaxa.

com, medlineplus.gov, WebMD, Agency for healthcare research

and quality (AHRQ), Drugwatch, Info web of University of North

Carolina, Healthline, Texas Heart institute, and Everyday health. All

pages examined were written for patient education.

Inclusion Criteria:

a) Website written in English Language

b) Patient directed Exclusion Criteria:

c) Broken or dead links

d) Written for experts or clinician

The material from each of the 69 WebPages was copied and

pasted into a separate Microsoft Word document. The documents

were then scrutinized for any text that was not related to

anticoagulation therapy. Examples include author information,

sponsor information, disclaimers, and hyperlinks to other websites,

copyright notices, references, citations, website information, and

URL’s. These types of text were then deleted from the document to

prevent skewing of the readability statistics. Each Microsoft Word

document was then subjected to readability analysis. Each page

was copied and pasted into an online readability assessment tool

www.readabilityformulas.com, to obtain 9 different readability

scores Flesch Reading Ease (FRE), Gunning Fog Index (GFI), Flesch-

Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), Coleman-Liau Index (CLI), SMOG

Formula (SMOG), Automated Readability Index (ARI), Linsear

Write Formula (LWF), Fry Readability Graph (FRG) and Raygor

Estimate Graph (REG), as well as the average grade level across all

9 calculators. Each of these 9 indices assesses the documents using

different variables and formulas to generate an estimated reading

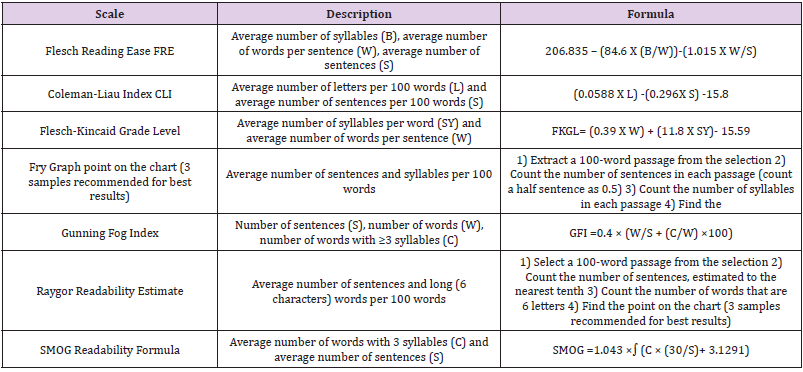

level. These variables and formulas are described in Table 1.

The FRE, FKGL, GFI, CLI, SMOG, ARI, and LWF provide numerical

reading scores via mathematical formulas, while the FRG and REG

provide graphical representation of the readability.

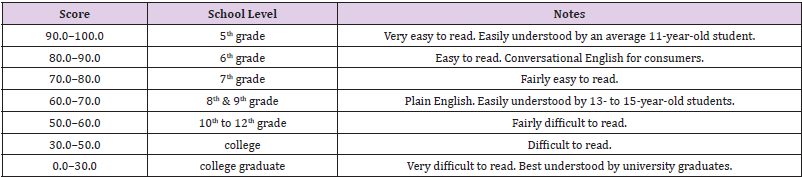

a) The FRE is a numerical score between 0 and 100, with a higher

number indicating a more readable document. It is influenced

by average sentence length and average syllables per word

[7]. Table 2 breaks down this scale to correlate the numerical

values with a level of difficulty and associated grade level [8,9].

b) The FKGL assesses the same variables as the FRE but generates

a grade level rather than a numerical score [10].

c) The GFI calculates a grade level based on average sentence

length and percentage of words with more than 3 syllables, i.e.

complex words.10 (4) The CLI generates a grade level based

on the average numbers of sentences and characters per 100

words [11].

d) The SMOG Formula uses the numbers of sentences and

complex words to generate a grade level [12].

e) The ARI calculates a grade level using the average word length

and average sentence length [13].

f) The LWF uses the numbers of complex words, easy words (2

syllables or less), and sentences to generate a grade level [14].

g) The FRG generates a graph using the average numbers of

syllables and sentences per 100 words, where the two lines

intersect indicates the reading level of the document [15].

h) The REG uses the average numbers of sentences and long

words (6 or more characters) per 100 words to generate a

grade level via an intersecting point on a graph, similarly to

the FRG [16]. The REG tends to estimate the grade level of a

document several points below the FRG and all of the other

readability indices. For this reason, medical researchers do not

use it as frequently [17] of these 9 tools, the FRE, SMOG, GFI,

and FRG are the most widely used readability calculators by

medical experts, the other scales being referenced less often

[9,17]. We felt that a composite average of multiple scales

would be a more accurate approach to determining the true

grade levels of these documents than any one or two scales

used alone.

The readability data were then analyzed using the endmemo

website (www.endmemo.com). Their basic statistical calculator

was used to generate means and standard errors of the mean for all

readability indices. First, since the 69 WebPages all had their own

readability scores, we sought to generate composite scores for each

of the 12 parent websites. For example, Xarelto.com had 6 individual

WebPages that were each analyzed separately for readability. We

used the stats calculator to generate averages for each readability

index, across these 6 pages, to provide composite values for Xarelto.

com as a whole. After the mean scores were calculated for each of

the 12 parent websites, we used the stats calculator to generate

an overall mean, with standard error, for each of the readability

indices. An overall grade level, factoring in all websites and scales,

was our final calculation.

Results

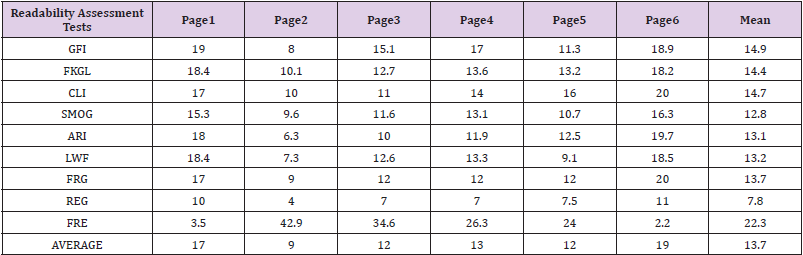

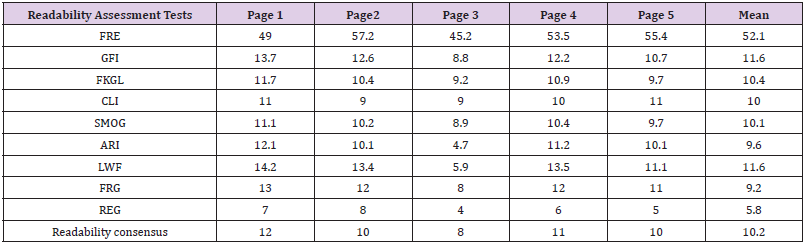

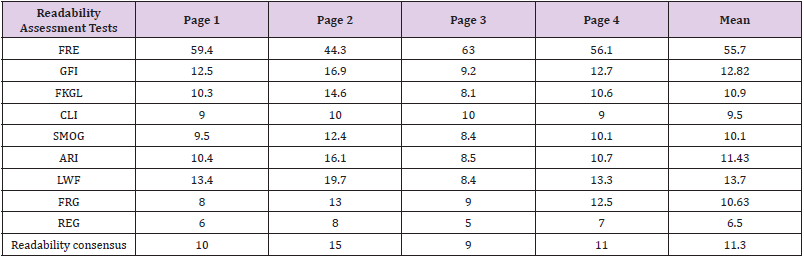

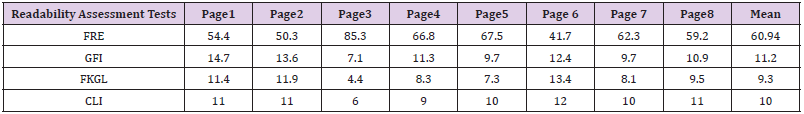

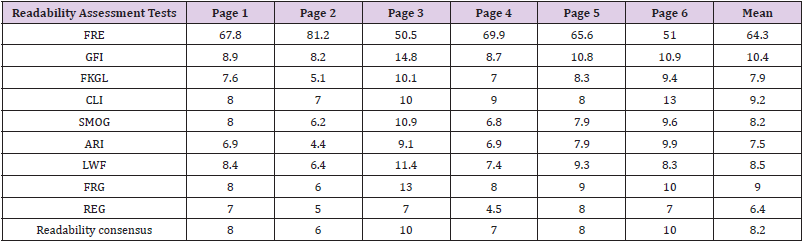

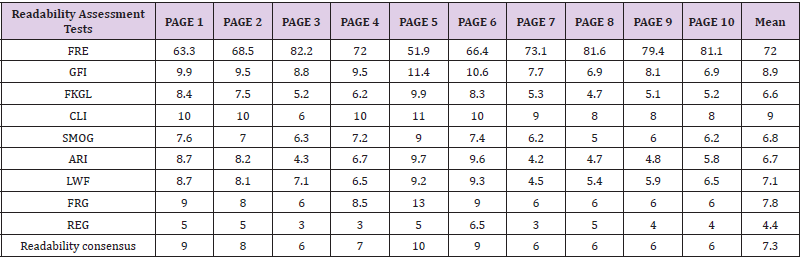

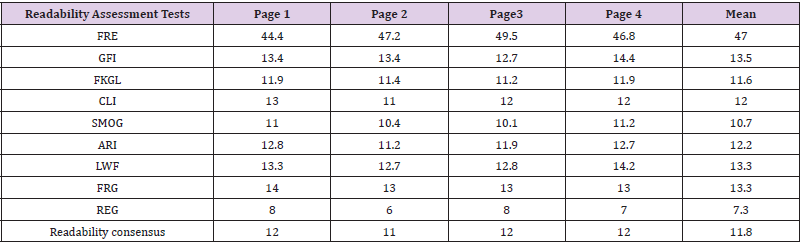

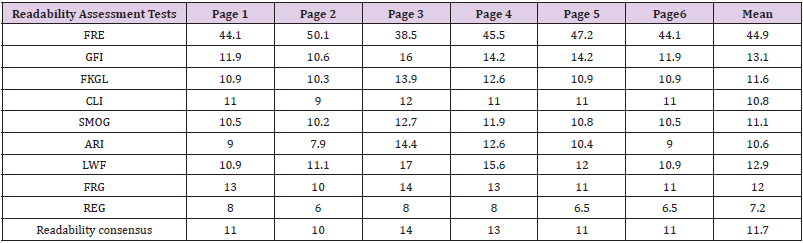

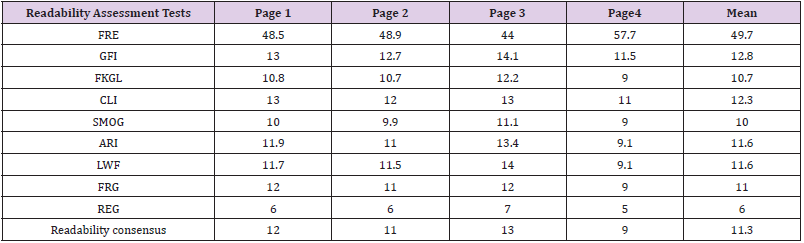

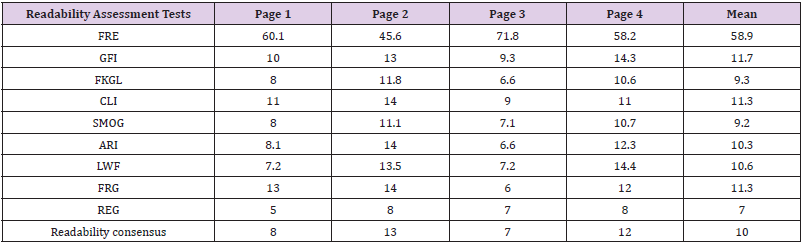

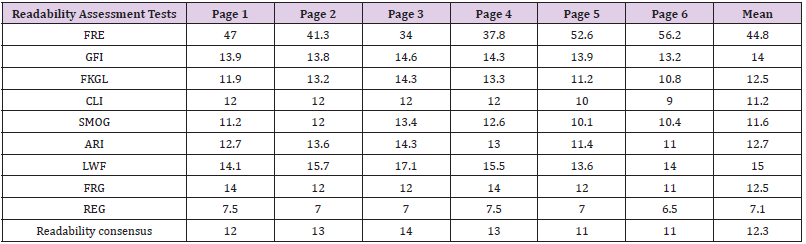

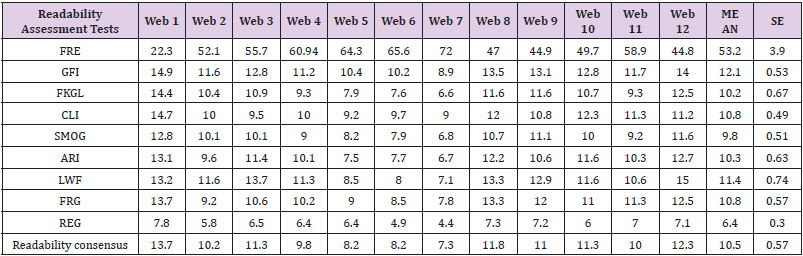

A total of 69 WebPages from 12 parent websites were analyzed for their level of readability using 9 different readability indices. Table 3 (A-L) provides a summary of the results broken down by website. The FRE scores has wide variability between websites, as shown by a wide range of 22.3 – 65.6, with a mean score of 53.2 +/- 3.9 standard errors of the mean; this score corresponds with a “fairly difficult” readability (10th -12th grade) Table 4. The FKGL scores displayed a tighter range, with a mean score of 10.3 +/- 0.54. The FRG graphs were somewhat similar between websites with a mean grade level of 10.8 +/- 0.57. The REG graphs were also similar, as demonstrated by the clustering, with a mean readability index of 6.4 +/- 0.3. The GFI, CLI, SMOG, ARI, and LWF means were calculated as 12.1 +/- 0.53, 10.8 +/- 0.49, 9.8 +/- 0.51, 10.3 +/- 0.63, and 11.4 +/- 0.74 respectively. The average reading levels for each website showed that they were written between a range of 7th and 14th grade, with the mean calculated at 10.5 +/- 0.57. This is correlated with a “fairly difficult” readability (Table 2). Xarelto. com is written at the highest level of all 12 websites with a grade level of 14 and a FRE score of 22.3, indicating that it is “very difficult to read, best understood by University graduates.” Table 5 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) patients guide and safety on blood thinner pills is the most easily read site out of the 12, with a grade level of 7 and a FRE score of 72; this indicates that it is of “Fairly easy to read” Table 6.

Discussion

Patients access healthcare information outside the healthcare environment in a variety of ways. Books, pamphlets, and other reading materials are common information resources. Family and friends also are a longstanding source of information, support, and advice. Experiential learning comes from watching others and by searching the internet, viewing television, video, and movies. Access to digital information available on the Internet has introduced a vast world of new possibilities as the use of computer-based learning interventions incorporates all of this information and learning approaches in a multimedia learning environment [18]. The ease with which a patient can search the Internet has made it one of the most important sources by which they acquire health information. People are increasingly turning to search engines and popular medical sites to answer all of their medical questions. With the Internet’s growing importance to patients, it is the responsibility of health care professionals to ensure that they are receiving highquality information at a reading level that the average person could easily understand. The National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) clearly state that all health information materials should be written below the 6th grade level to adequately ensure that a majority of the American population can understand it [19,20].

The phrase “Blood thinners” was searched on Google, subsequent analysis of the top 12 resulting websites showed that they are all written at levels that exceed the recommendations. The FRE, FKGL, FRG, GFI, CLI, SMOG, ARI, and LWF scales demonstrated that these sites were authored at difficulty levels above 8th grade, frequently reaching readabilities of 10th grade and higher. The REG calculations showed that most of the sites fell around the 6th - 7th grade, but this graph has been shown to underestimate readability several levels below the other scales [21]. Because the REG uses word length and the number of sentences to compute its results rather than syllable number and sentence length (which are better predictors of readability), it tends to lead to falsely low readability results [22]. Thus, we do not believe the REG results to be as accurate as the other scales that we used. Xarelto.com is written at the highest level of all 12 websites with a grade level of 14 and a FRE score of 22.3, indicating that it is “very difficult to read, best understood by University graduates.” Tables 7-15. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) patients guide and safety on blood thinner pills is the most easily read site out of the 12, with a grade level of 7 and a FRE score of 72; this indicates that it is of “Fairly easy to read.” Table 2 Although this meets the reading level of the average American, it is still above the USDHHS recommendation for PEM readability.

The readability level of patient information material contrasts with the observed patients’ abilities to read. One third to one half of English-speaking patients have difficulty reading material at the 10thgrade level.24 25 Another compounding problem is that a patient’s educational level does not automatically guarantee proficiency at that same level. Patients observed reading abilities are usually 3 to 5 grade levels below what they report as grade completed [23]. This study is limited in certain ways, which should be considered during further research. While we assume that patients use the Google search engine as a tool to research anticoagulation therapy, we do not have any conclusive evidence that patients use this particular method more than other search engines or search methods. While the PEM’s that we studied were written above the recommended grade level, we did not consider whether patients are still able to gain valuable information from these PEMs and to what degree they are able to do so. We did not consider whether patients are selfselecting in regard to accessing internet-based PEMs; patients who access these PEMs in the first place might be more likely to read at a sufficient grade level to understand the content. Additionally, charts, data tables, and other non-text-based information, which were not analyzed via the readability formulas, might provide valuable information to patients.

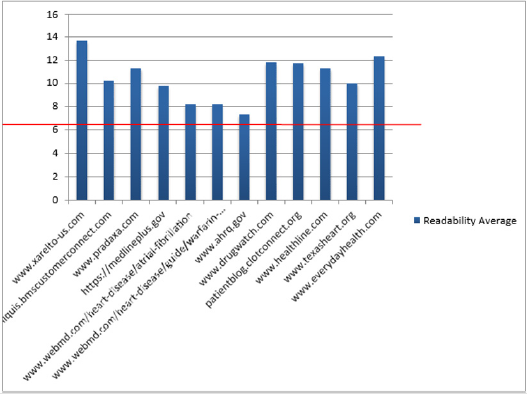

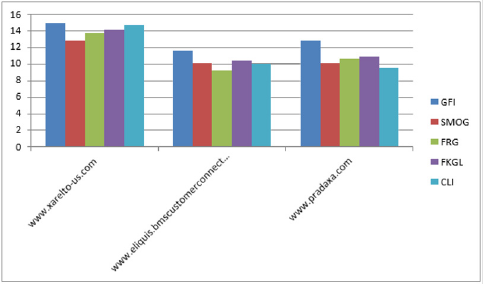

Patients taking anticoagulants who are at risk for bleeding and thrombosis need to learn and understand their condition. As increasing numbers of elderly patients with atrial fibrillation receive warfarin and other NOAC drugs, it is imperative to device an effective communication. Patient information should be written at an appropriate reading level, and its readability could be determined by using the various readability formulas. The National Work Group on Literacy and Health also recommends that material be written at or below the 6th-grade level, [24-30] because material written at higher levels is less likely to be read or understood. Developing patient information at a low readability level is necessary but not sufficient to improve comprehension. Our study suggests that health information sites on anticoagulation therapy need to be rewritten at more understandable levels. There are many ways that these sites can be altered to bring their readability scores down (Figure 1 and Figure 2). First of all, many of the writings used a large number of medical terms; using smaller, less scientific words has the potential to drop many of the readability scores substantially. Limiting sentence length and reducing the complexity of sentence structure can also reduce scores and make the document far more easily understood. Other methods of communication, and written information that uses figures, pictograms, large font, and other characteristics, may also improve comprehension [31].

Figure 2: Comparing websites on the most popular direct thrombin inhibitors Y axis- Grade level X axis- Website comparison- Xarelto/eliquis/Pradaxa.

Conclusion

The Internet-based patient education materials on anticoagulation therapy are written at levels far above the recommendation of 6th grade. Due to a wide-spread pool of information, which can be personalized, Internet can enhance health literacy, health related knowledge and support people to become responsible for their own health. Hence, much attention needs to be paid to readability of these health education materials. Current Internet-based PEMs on anticoagulation therapy should be revised to make them more easily understood by the average American.

References

- Steven B Cohen, William Yu (2009) The Concentration and Persistence in the Level of Health Expenditures over Time: Estimates for the U.S. Population, 2008-2009.

- The Joint Commission. What did the doctor say? Improving health literacy to protect patient safety. Health Care at the Crossroads series.

- (2003) National Center for Education Statistics. National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL).

- (2000) United States Dept. of Health and Human Services. Saying it clearly.

- Albright J, de Guzman C, Acebo P, Paiva D, Faulkner M, et al. (1996) Readability of patient education materials: implications for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res 9: 139-143.

- Flesch R (1948) A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology 32(3): 221-233.

- Cherla DV, Sanghvi S, Choudhry OJ, Liu JK, Eloy JA, et al. (2012) Readability assessment of internet-based patient education materials related to endoscopic sinus surgery. The Laryngoscope. 122(8): 1649-1654.

- Kasabwala K, Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Baredes S, Eloy JA (2012) Readability assessment of patient education materials from the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 147(3): 466-471.

- Gunning R (1952) The Technique of Clear Writing. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Coleman M, Liau TL (1975) A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. Journal of Applied Psychology 60(2): 283-284.

- McLaughlin GH (1969) SMOG grading: a new readability formula. Journal of Reading 12: 8.

- Senter RJ, Smith EA (1967) Automated Readability Index. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: Aerospace Medical Research Laboratories 5(6).

- Christensen GJ (1997) Readability helps the level. Northridge, California: California State University; 1997.

- Fry E (1968) A readability formula that saves time. Journal of Reading.11(7): 513-516.

- Raygor AL (1977) The Raygor Readability Estimate: a quick and easy way to determine difficulty. In: Pearson PD, ed. Reading: Theory Rap. Clemson, SC: National Reading Conference pp. 259-263.

- Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S (2010) Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 468(10): 2572-2580.

- Weiss BD, Hart G, McGee DL, D’Estelle S (1992) Health status of illiterate adults: relation between literacy and health status among persons with low literacy skills. J Am Board Fam Pract 5(3): 257-264.

- Weiss BD, Blanchard JS, McGee DL, Hart G, Warren B, et al. (1994) Illiteracy among Medicaid recipients and its relationship to health care costs. J Health Care Poor Underserved 5(2): 99-111.

- Deborah Lewis (2003) Computers in Patient Education. 21(2).

- Walsh TM, Volsko TA (2008) Readability assessment of internet-based consumer health information.

- Respiratory Care 53(10): 1310-1315.

- Raygor AL (1977) The Raygor Readability Estimate: a quick and easy way to determine difficulty. In: Pearson PD, ed. Reading: Theory Rap. Clemson, SC: National Reading Conference 1977: 259-263.

- (2011) National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). National Center for Education Statistics. 2011.

- Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Scott TL, et al. (1999) Health literacy among medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. JAMA 281(6): 545-551.

- Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR (1998) Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease: a study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med 158(2): 166-172.

- Estrada CA, Barnes V, Hryniewicz MM, Collins C, Byrd JC, et al. (1999) Low literacy and numeracy are prevalent among patients taking warfarin. J Gen Intern Med 14: 27.

- (1998) The National Work Group on Literacy and Health. Communicating with patients who have limited literacy skills. J Fam Pract 46(2): 168-176.

- Weiss BD, Coyne C (1997) Communicating with patients who cannot read. N Engl J Med 337(4): 272-274.

- Doak CC, Doak LG, Root J (1996) Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott; 1996.

- (2015) Pew Research center, http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005- 2015/

- (2013) Computer and Internet Use in the United States p. 20-569.

- (2007) Karen Beauregard, Kelly Carper. Outpatient Prescription Anticoagulants Utilization and Expenditures for the U.S. Civilian Nonin stitutionalized Population Age 18 and Older, 2007.

Research Article

Research Article