Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Kathleen Fasing*, Sangeeta Lathkar-Pradhan and Preethi Patil

Received: September 03, 2022; Published: September 09, 2022

*Corresponding author: Kathleen Fasing, University of Michigan Cardiovascular Center, 2A- 58691500 East Medical Center Drive Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5869, USA

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2022.46.007298

This Telemedicine study assists patients in adopting self-care behaviors and is designed for early recognition and treatment of cardiac arrythmias. Telemedicine allows health care professionals to evaluate, diagnose and treat patients within their own home [1] by connecting via video or telephone visits. The arrhythmia care with such visits is aimed at increasing the subject’s self-efficacy of arrhythmia care and increasing behaviors to manage the arrhythmias [1,2]. The goal of the study is to utilize telemedicine to provide earlier diagnosis of arrhythmias and increased patient involvement in one’s own self-care.

Keywords: Telemedicine; Arrhythmia; Self-Efficacy; Behavior

The purpose of the study, Telemedicine: Enabling Patients with Arrhythmias in Self-Care Behaviors (T: EPASB) is to provide an alternative to in person visits, decrease the time of diagnosis and treatment of an arrhythmia via the internet and enable patients to improve self-efficacy of arrhythmia care behaviors. Self-efficacy can be defined as the individual’s belief in oneself to handle a set of circumstances or changes in physical or mental well-being [2,3]. The first outcome of the study displaying a difference in

a) The time of arrhythmia recognition

b) The time of arrhythmia diagnosis by a health care provider, and

c) Time of treatment initiation, comparing those treated with telemedicine versus those treated with in person standard visits. The second outcome of the study is a comparison of self-efficacy of arrhythmia knowledge and care, medication knowledge and use, and functional activity. The goal is to see if there is a difference in these parameters in the telemedicine versus the in-person visit individuals or if there is no difference in these measured parameters [3].

University based tertiary care clinics, which treat irregular heart rhythms, are known as arrhythmia clinics and formally called electrophysiology departments [4]. These departments have been in existence prior to the early 1960’s and their technology has evolved over time. Visits include discussions of abnormal heart rhythms, prescribe medications and plan implanting of devices such as pacemakers (PPM) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) [4]. The continued improvement in technology and expansion of such departments has increased the number of appointments, dual appointments for arrhythmia and device coordination with other cardiology sub-specialties [5]. This increased number and length of appointments places stress upon patients with longer drives, wait times, and the cost of parking, food, and gas to drive to the appointments [6]. With such stressors, a need for computer assisted video visits has evolved [6]. The monitoring of arrhythmias includes home monitors, external monitors, implanted monitors (loop recorders), permanent pacemakers (PPMs) or implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs).

The T:EPASB is based upon studies showing improved clinical outcomes with the use of telemedicine. The TRUST trial compares the use of a telephone video conference to conventional in person visits with individuals with ICDs. The TRUST trial determined the efficacy and safety for monitoring ICDs and the reduction of in person visits [7,8]. This study displayed an adverse event rate of 10.4 for each group [7,9] and no difference in the telemedicine versus the in person visit group. The Poniente trial determined there was no difference in arrhythmia detection and functional capacity in monitoring elderly patients with pacemakers via home monitoring compared to in person monitoring [10]. The CHOICE AF was a pilot study to test the feasibility of a brief telephonebased program to target improving cardiovascular risk factors and health related quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation [11], showing great potential for a telephone-based program. A study by Ryan, et. al. [12] verified the efficacy of theory based Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) intervention utilizing a cellular phone application to increase women’s initiation and long-term maintenance of osteoporosis self-management behaviors. This study takes a chronic disease state, osteoporosis, and combines ITHBC prompted behaviors with a cellular phone application to assist women in behavior change [13]. Self-efficacy is used as a key component in managing one’s health noting patient empowerment in the management of chronic disease conditions such as diabetes mellitus and heart failure. The study identified the essence of telemedicine in its ability to empower patients with skills in managing one’s chronic health condition.

Theoretical Framework Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) was used in guiding this study as it notes the importance in assisting individuals in becoming increasingly involved in their own health care [2]. This theory links a relationship between the way one views one’s own health care and an overall sense of wellness. Dr. Ryan highlighted the need to

1) Have a change in how one reacts followed by

2) One’s resultant behavior with an improved sense of wellness (when assisted with behavior changes). Essential components for behavior change include a desire to change, self- reflection, positive social-influence and support required in creating the change [2].

This study utilizes the Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) in assisting the individual being treated to become increasingly involved in one’s own health care decisions and treatment [2]. The theory links a relationship between the way one views one’s own health care and an overall sense of wellness [2]. Dr. Ryan’s displays this theory in a study of those with chronic health care diagnosis’ and improving specific health care behaviors.

It highlights the need to

1) Have a change in how one reacts, followed by

2) One’s resultant behavior with an improved sense one’s wellness (when assisted in such a behavior change). Essential components in the behavior change include a desire to change, self-reflection, positive social influence, and support required to make the change [2].

(Table 1).

Monthly arrhythmia visits -either video visits or phone visits (only when video not available) are compared with in person arrhythmia visits occurring every six months.

Treatments are the same for both groups and include:

1) Patient interview and discussion of symptoms with the arrhythmia and actions taken when having an arrhythmia.

2) Review of patient data including home blood pressures, data from devices such as pacemakers, defibrillatorcardioverters, and loop recorders (this is obtained in person with the in person visit group and via downloads of arrhythmia data and tracings via at home monitors. These tracings are obtained pre and post video visits via our support monitoring department. Electrocardiograms (ECGs) are obtained at local clinics and hospitals.

3) Counseling on behavior changes such as taking rest periods, increasing fluid intake with some atrial arrhythmias, recommending the use of structured exercise on an ongoing basis, referral to nutritional counseling for weight loss.

4) Discussing specific arrhythmia events, keeping logs of such events, counseling on associated symptoms with arrhythmias, discussing medications such as beta blockers and calcium channel blockers to decrease arrhythmia events.

5) All methods of arrhythmia analysis, care, education, medication use, and activity adjustments and behavior changes are the same for both groups. The telemedicine group has more time for discussion and verification of information. The telemedicine group also has no constraints such as driving to the appointment, taking of vital signs with arrival and rooming with the medical assistants. The time of direct discussion regarding arrhythmias is more dedicated than the conventional in person visit [6] (Appendix A).

Arrhythmias are multifactorial and can cause no symptoms versus symptoms such as palpitations, fast and pounding heart beats, sweating, chest pain and or pressure, anxiety, fear, and depression [14]. A single survey may not capture the data experienced by the subject and the three surveys are an excellent encapsulation of the arrhythmia experience. The MUSE survey was tested for validity and reliability in measuring patients’ self-efficacy of medication knowledge and use [15]. FSES displayed good internal consistency and satisfactory criterion and convergent validity in assessing the degree of confidence self-functioning while facing decline in health and function [16]. ASTA, displayed content validity for all items, and internal consistency [17,18]. (Appendix B).

The T:EPASB utilized telemedicine visits to discuss arrhythmia symptoms and treatment options. These appointments adopted in home computers for video visits and wasted no time as with standard visit arriving and rooming of the subject. The telemedicine group had more time to ask questions, discuss adjusting rate control medication and dosages per symptoms, options for antiarrhythmics, side effects of medications, weight loss, exercise, and hydration. There was dedicated time to identify arrhythmia triggers, learn of minor adjustments in medications which the subject could adjust, increasing fluid intake, and increasing activities when no arrhythmias are present. The standard visit group was given the same information, but the duration of the appointment was much more limited. Information and teaching focused on increasing the subject’s self-efficacy of medication use, arrhythmia understanding, and increasing functional activity. Discussion included confirming subject’s knowledge, increasing self-reflection and subject’s social support.

All statistical computations were performed using SPSS version 28.0. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test and shown as Number (%). Continuous variables were compared using T-test indicated as Mean ± S.D. Number of days to event (early recognition\diagnosis\treatment) for the 2 groups was shown using Kaplan Meir curves. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

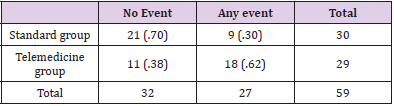

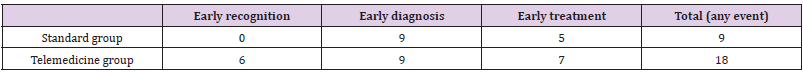

Table 2: Comparing the number of events in both the groups *(P = 0.01).

Note: *Chi-square test was used.

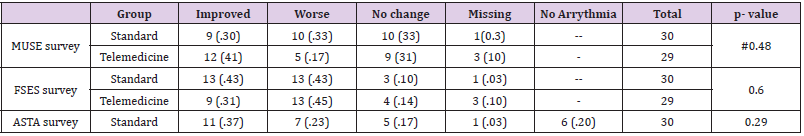

Analysis of time to recognize and treat resulted in a 2:1 relationship between earlier discovery of the arrhythmia, earlier diagnosis, and earlier treatment of the arrhythmia in the telemedicine group versus the standard visit group (Table 2). The MUSE and ASTA survey questions reached significant p-values for the telemedicine group with a p value of 0.48 and 0.29 respectively. The FSES survey (Appendix D) did not reflect an increase in one’s self-efficacy of activity as the p value for the telemedicine group was 0.60. The Telemedicine: Enabling Patients with Arrhythmias in Self-Care Behaviors Study highlights several expected outcomes. The study gives merit to the use of video and telephone visits to interact with subjects and assist in enabling their understanding and self-efficacy of medication and arrhythmia knowledge and management. The study failed to reach the outcome of significance in enabling subjects in increasing their activity self-efficacy (FSES). There is however, empiric and individual data which shows some of the telemedicine subject greatly understood and increased their activity and increase their self-efficacy of using increased activity in controlling a component of their arrhythmia. The first outcome of the study, to recognize, diagnose and treat the arrhythmia sooner within the telemedicine group was met and resulted in treating these events sooner with a 2:1 ratio of recognized, diagnosed and treated events within the telemedicine group. The study illuminates the importance of early recognition and treatment of arrhythmia events and the use of telemedicine to increase the self-efficacy of medication understanding and use and arrhythmia knowledge. Telemedicine coincidentally also coincided with an international pandemic with Covid-19. This study was in the design stage and received IRB approval in August 2019, well before the pandemic reached its initial peak in March 2020. Telemedicine has since been adopted with many medical and nursing practices and has continued great applicability within the electrophysiology and arrhythmia care arena. We continue to adopt telemedicine in several of our clinics and hope to further collect data on its advantages. The use of the Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change is utilized in assisting the subject in recognizing one’s selfefficacy of arrhythmia, medication and activity knowledge and use in managing one’s arrhythmia. It guides reinforcing the subject’s knowledge, reinforcing social support in managing an arrhythmia and helping the subject understand their own readiness to change such behaviors and degree of support which is available.

The chief limitation of the study was the ill matched design timeline of treatment with the standard group given the threemonthly visits versus six-month time of appointments and the temptation to treat those within the telemedicine group sooner (our study showed both groups receiving prompt care when changes in arrhythmias and other symptoms occurred). Discussion and Conclusions Telemedicine is a viable method to minimize the time to recognize, diagnose and treat arrhythmias and the study’s telemedicine group showed significance of this endpoint and selfefficacy of medication understanding and use and arrhythmia knowledge as calculated with scores from MUSE and ASTA Surveys. The Telemedicine arrhythmia study failed to reach significance of activity (FSES) however empiric data shows some individuals greatly increased one’s activity level. At the University of Michigan Electrophysiology department, we now have data noting the benefits of telemedicine within our arrhythmia population. The positive results of this telemedicine study mimic the results of the CHOICE AF study [11] in improving specific quality of life parameters (Appendix C and E- MUSE and ASTA surveys) and build upon its telephone modality to now include video visits. This study encourages further use of telemedicine in the care of our patients. Table 1- The final limitation of the study is the small sample size. Depending on formula utilized one may note that the size of the study is adequate to reach significance. This study was a pilot study to determine the ability to reach listed goals with telemedicine with those with arrhythmias. A larger study in the future would be beneficial. This study was the pilot study for telemedicine within the arrhythmia setting. Post hoc calculations give the power at 70.3% and an addition 7 subjects in each group would be preferred for an ideal power in determining significance.

Telemedicine is a viable treatment option to minimize the time to recognize, diagnose and treat arrhythmias and the telemedicine group showed significance of this endpoint and significance of self-efficacy of medication understanding and use and arrhythmia knowledge as calculated with scores from MUSE, FSES and ASTA Surveys. The Telemedicine arrhythmia study failed to reach significance of the self-efficacy of activity using the FSES survey. Individual subjects greatly increased their self-efficacy of activity within the study and greatly increased their exercise. Utilizing telemedicine has become accepted within our practice for reasons involving the demands of care during the Covid 19 epidemic and the need for an alternative appointment option [3]. It is reassuring to our group that we have data noting the benefits of telemedicine specifically within our population of arrhythmia care subjects. This significance of time to recognition, diagnosis and treatment which is evident in the telemedicine group mimics previous studies on the utilization of telemedicine with arrhythmia subjects. The self-efficacy of medication knowledge and use and arrhythmia understanding have shown significance in the study.

Of note- Arrhythmia data may be obtained from devices, loop recorder etc with both groups at any time (Figure 2) (Appendix F).

(Figure 3 & Tables 4-8).

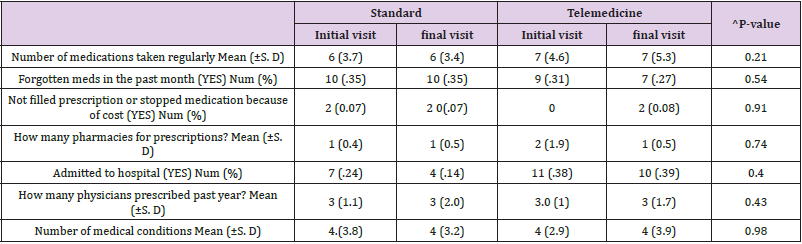

Table 4: MUSE survey.

Note: ^p-value is comparing only the final visit between the 2 groups. Means were compared using a T-test and the percentages were compared using a chi-square test.

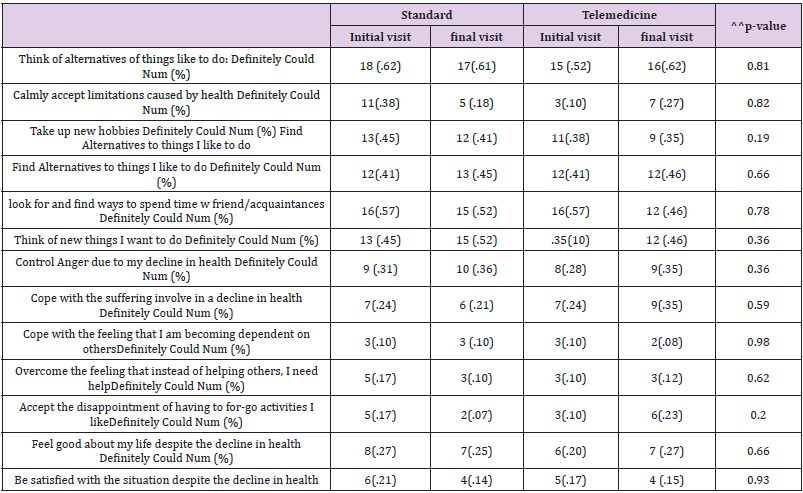

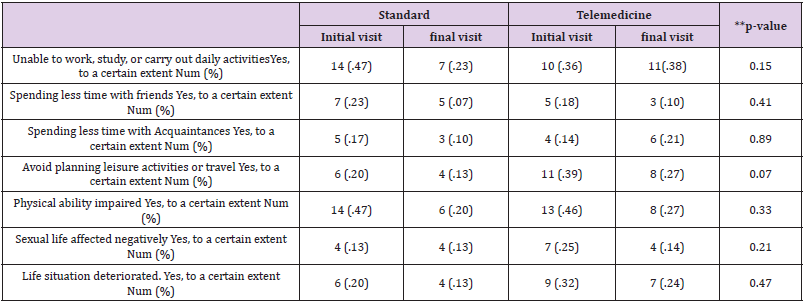

Table 5: FSES survey.

Note: ^^p-values are comparing only the final visits between the 2 groups. Chi-square test was used.

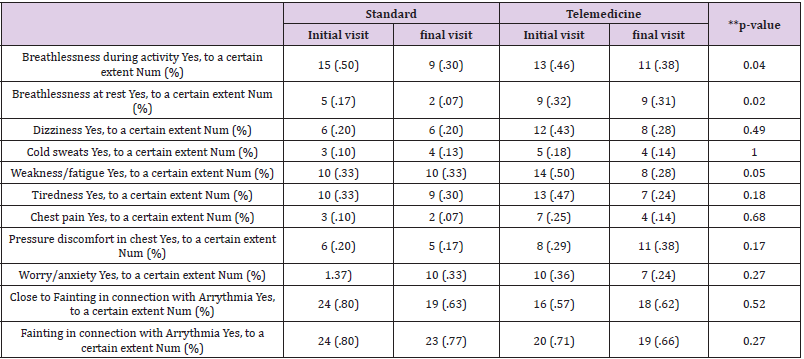

Table 6A: ASTA Symptom scale.

Note: **P-values comparing final visits between the 2 groups. Chi-square test was used.

Table 6B: ASTA Symptom scale.

Note: **P-values comparing final visits between the 2 groups. Chi-square test was used.

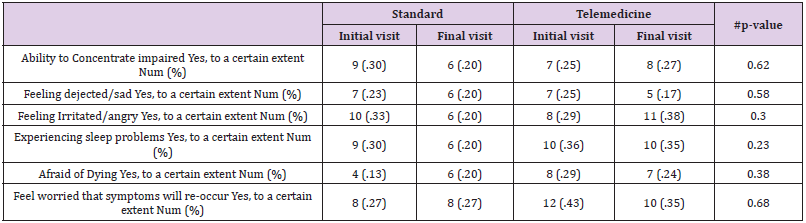

Table 6C: ASTA Mental subscale.

Note: #P-values comparing the final visits between the 2 groups. Chi-square test was used.

Table 7: Comparison of final score MUSE survey, FSES survey, & ASTA survey.

Note: # Muse survey: Only some of the questions were used. Chi-square test was used to obtain the p-value.

Table 8.

Note: # Muse survey: Only some of the questions were used. Chi-square test was used to obtain the p-value.

As each step down on the line indicates an event, the figure gives you a visual representation of the number of events within the time-period. The green line represents the telemedicine group. As you can see on this line, they are many step downs. Each step down indicates that an event like early recognition/ diagnosis/ treatment has occurred. They were 18 events in this group. The blue line represents standard group. As you can see on this line, they are only few step downs indicating few events occurring in this group. About 9 events occurred in this group (Table 2). Compared the baseline visits or Initial visits between the standard and telemedicine group, there was no significant differences except for the following variables (Tables 9-11).

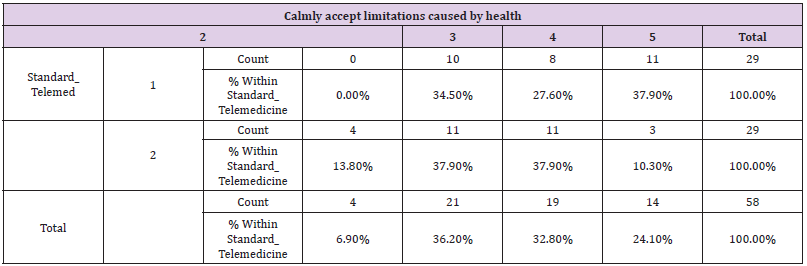

Table 9: Standard_Telemed * Calmly accept limitations caused by health Crosstabulation.

Note: P= 0.03 chi-square test was used.

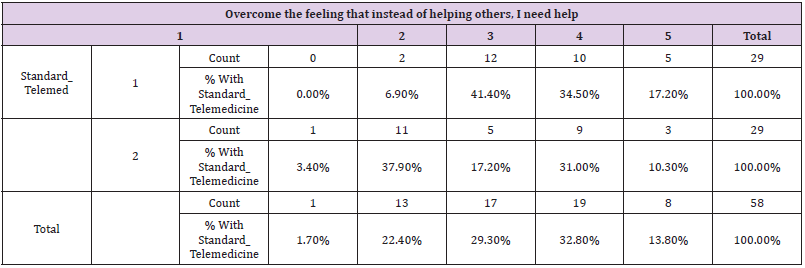

Table 10: Standard_Telemed * Overcome the feeling that instead of helping others, I need help Crosstabulation.

Note: P= 0.03. A chi-square test was used.

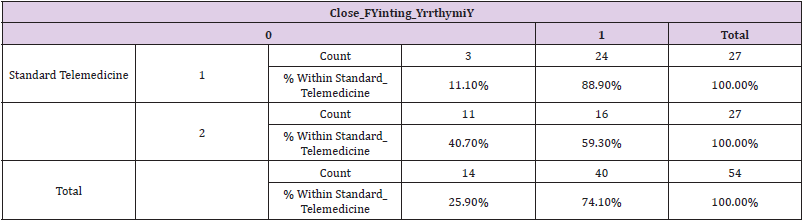

Table 11: Standard_Telemedicine * Close_FYinting_YrrthymiY Crosstabulation.

Note: P=.01 Percentages between the groups were compared using a chi-square test.